The Not-Quite-Korean Film Page

"Air Doll", "Stoker", "The Last Stand", "Blood: The Last Vampire"

As time passes, Korean cinema continues to become more and more international in its orientation. It's no longer seen as unusual for a Korean film to be set in a foreign country, or for a well-known international star like Isabelle Huppert to appear in a Korean film, as she did in Hong Sang-soo's In Another Country.

At the same time, Korean talent is becoming more active in the international film community. The talented Bae Doona can point to both Japanese films (Linda Linda Linda, Air Doll) and Hollywood films (Cloud Atlas) in her filmography. Korean directors like Park Chan-wook and Kim Jee-woon have both shot films in Hollywood. Technically, these works don't qualify as Korean films, but we realize that fans of Korean cinema will have a special interest in them.

Therefore we have created this page to provide reviews of films that are not quite Korean, but which nonetheless hold some significance for Korean cinema enthusiasts. This includes both productions that have been made with contributions from Korean talent, films by and about the Korean diaspora, and films which thematically hold some special interest for fans of Korean cinema.

Reviewed below: Koryo Saram (2007) -- Air Doll (2009) -- Our Homeland (2012) -- Comrade Kim Goes Flying (2012) -- Oldboy (2013) -- Stoker (2013) -- Seoul Searching (2015) -- Terminator Genisys (2015) -- Spa Night (2016) -- Okja (2017).

When 16 year-old Saltanat Tuktubayeva from Kazakhstan came onto the Survival Audition K-Pop Star 3 reality show stage recently, she had come to the native land of her father. How her father's father, and tens of thousands of other ethnic Koreans, ended up in Kazakhstan is a long, arduous story, well-summarized in Y. David Chung and Matt Dibble's 60-minute documentary Koryo Saram.

Using an old school word for the Kingdom peninsula and the Korean word for "person", "Koryo Saram" is the name ethnic Koreans throughout Russia and the former Soviet Republics use to refer to themselves. Those Koreans traveled to Russia across the 17 kilometer border initially due to famine, but later many more fled to escape Japanese imperialism. Even though many left to flee the Japanese and many fought against the Japanese later, Stalin saw them as 'unreliable people' who might support the Japanese during World War II and forcibly moved them from coastal regions like Vladivostok to what is now modern Kazakhstan and Uzbekistan in Central Asia. Because the USSR heavily controlled her people's movement, these ethnic Koreans did not have the freedom to return to either North or South Korea when the Korean War Armistice Agreement occurred. (A small delegate of Koryo Saram were sent to North Korea as advisers to Kim Il-sung, but he soon sent them back.)

Using an old school word for the Kingdom peninsula and the Korean word for "person", "Koryo Saram" is the name ethnic Koreans throughout Russia and the former Soviet Republics use to refer to themselves. Those Koreans traveled to Russia across the 17 kilometer border initially due to famine, but later many more fled to escape Japanese imperialism. Even though many left to flee the Japanese and many fought against the Japanese later, Stalin saw them as 'unreliable people' who might support the Japanese during World War II and forcibly moved them from coastal regions like Vladivostok to what is now modern Kazakhstan and Uzbekistan in Central Asia. Because the USSR heavily controlled her people's movement, these ethnic Koreans did not have the freedom to return to either North or South Korea when the Korean War Armistice Agreement occurred. (A small delegate of Koryo Saram were sent to North Korea as advisers to Kim Il-sung, but he soon sent them back.)

That is the shorthand version of how so many ethnic Koreans ended up in Kazakhstan. Chung and Dibble's documentary goes into greater detail through the well-placed use of photos, stock footage, and the heart-wrenching stories of the elder Koryo Sarams Chung meets on his journey through Kazakhstan. Chung narrates the film, mentioning how he was struck by the surreal multiculturalism of Almaty, Kazakhstan's largest city, a multiculturalism that seemed familiar to him, an American, yet different. He travels throughout the country learning from elders, scholars, and performances what life for the Koryo Saram was like in the past from the elders, and what it is like now for the youth.

The long tradition of trains and cinema provides many of the initial images. The Koryo Saram were put on trains to forcibly relocate them, trains Koryo Saram call 'ghost trains' due to the many who died on the journey. Since the dead could not be properly buried, ancient Korean tradition argues those souls remain restless about the countryside. This discussion is complemented with ghostly stock footage in a deteriorating state originally, or made to look that way for impact. Either way, it works. Equally powerful are some of the subtle gestures, such as the simple cutting of an apple for guests in one scene, apples having originated from what is now Kazakhstan. Kimchi is used as cultural mash-up metaphor in the film, since the cabbage to make it is grown in Kazakhstan from seeds from South Korea, but the spices are indigenous of Kazakhstan, a variation on the 'melting pot' model of multiculturalism that allows for differences to stand out more than, say, in a stew or soup.

Chung's narration points out many ironies of the suppression of Korean culture and language during Stalin's reign. By outlawing the direct teaching of the language, a rare dialect of Korean was maintained since the 'standard' Korean couldn't be written or read. But now with the opening up of Kazakhstan to the riches of South Korean import/export businesses and the dreamy draw of Korean pop stars, interest in the standard Korean language has rejuvenated. This freedom results in further ironies for Chung since the result is a reduction in the presence of the former dialect. Chung, a visual artist, underscores how much of the language and traditions have been maintained through the mediums of theatre and song, as well as rituals such as weddings and a boy's first birthday. In spite of the lingering traditions, the elderly Koryo Saram worry about the imperatives made by South Koreans in Kazakhstan, be it businesses demanding a particular commercial approach or South Korean Christians demonizing their shamanistic views. In addition, one Koryo Saram youth interviewed in the film mostly fraternized with Russians and Kazakhs until university, so those influences wield strongly as well. She is now majoring in Korean, hoping to travel there one day. As the elders fear, this is not so much the Korean of her Koryo Saram past, but the Korean of the present, that bright, shiny, and for some, prosperous Korean that brought Tuktubayeva to South Korea in hopes of K-Pop stardom. (Adam Hartzell)

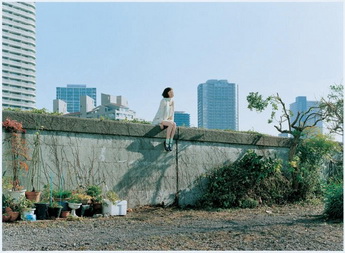

Nothing may pique our cinephilia more than anticipating a film where a great director gets together with a great actress or actor. For those of us who follow contemporary East Asian cinema, Air Doll provides such a cinematic convergence.

Air Doll finds itself on the 'Not Quite Korean page' because it is at its core a Japanese film. The film takes place in Japan and the dialogue is in Japanese. It is produced by Japanese funders, is based on a Japanese manga, and is directed by a film festival favorite of Japanese descent, Kore-eda Hirokazu.

Air Doll finds itself on the 'Not Quite Korean page' because it is at its core a Japanese film. The film takes place in Japan and the dialogue is in Japanese. It is produced by Japanese funders, is based on a Japanese manga, and is directed by a film festival favorite of Japanese descent, Kore-eda Hirokazu.

Kore-eda first impressed audiences with Maborosi, where we slowly watched a widow and widower tentatively approach an ambivalently arranged union. Loss and letting go continued to be a theme for Kore-eda in After Life, Distance, Still Walking, and I Wish. But Kore-eda reached his arguably masterful peak with the beautiful sadness of Nobody Knows, a film about siblings making due after being abandoned by their unstable mother. Although one must stretch to apply Kore-eda's themes of loss and letting go to Air Doll, this film continues an equally consistent theme of Kore-eda's, loneliness, while highlighting Kore-eda's skill at demonstrating the simple power of the observed and the unspoken.

As much as this film is dependent on the stewardship of a great director like Kore-eda, there is a great actress in this film as well, Bae Doo-na. The impact of this film is heavily dependent on her performance, and her presence is why this falls into 'Not Quite Korean' page.

Although a greatly respected actress by many in the South Korean film industry and by those who come to this website, Bae's talent has not always resulted in huge home box office draws. Her presence wasn't able to save Tube, the failed Korean blockbuster that took Speed underground to the subway, while the success of Bong Joon-ho's The Host was not reliant on her performance. Because of this, Bae's star status is an enigma, something hard to place. The great description of Bae's standing in the larger cinematic constellation of world cinema can be found in Beck Una's wonderfully concise essay in the July-August 2009 issue of Korean Cinema Today. "By all account[s], she does not have the looks of a typical international star. The face which can make perspective powerless and is beyond intimacy. Her face is at the very unique spot where you can hardly argue whether it is pretty or not, or tell where she is from. Then we might call her an actress from earth, but even that seems far fetched at times.?" At the end of the piece, Beck resolves that "Perhaps it would be more apt to call her a universal actress."

As a universal actress in the age of hyper-globalization, Bae is free to venture anywhere. At first, Bae traveled across the watery and cultural divide that separates South Korea and Japan to extend the reach of her star status in the land of her country's former colonizer. There was her role as a zianichi (a Japanese resident of Korean dissent) in the Japanese TV series Someday and her role as a South Korean high school exchange student in the fun, fun, fun Linda, Linda, Linda. Along with the otherworldly visage noted by Beck, perfect for the uncanny nature of a doll coming to life, as an actress yet to be fully competent in the Japanese language, Bae's linguistic ability was perfect for Air Doll. Kore-eda has continually said how impressed he was with Bae's ability to demonstrate her character's growth into the language even within the sequential discontinuity required by the filming schedule. Likely due to both her performance in Air Doll and what Beck pegs as Bae's 'universal actress' aura, the Wachowski siblings and Tom Tykwer cast her to star in the other-worldly neo-Seoul section of Cloud Atlas (2012), along with having her appear as cross-racial characters in different time periods of the film.

Ironically, Bae's role in Air Doll runs counter to what I and some other critics have appreciated about Bae, her willingness to go against the glamour imposed upon and pursued by many actresses (Korean or otherwise) and instead play roles where the characters are plain and not beautiful, at least not within the mainstream constructs of beauty. Watch her in Barking Dogs Never Bite and Linda, Linda, Linda and you don't see the doll that Bae becomes here. In Air Doll, Bae's beauty and Bae's body are on full display. Bae is an actress comfortable in her own skin, a good thing because she's in only her skin a lot in Air Doll. This constant nakedness of her indeed beautiful body might perpetuate the media-imposed feelings of inadequacy about one's body for some women as Lee Byung-heon's chiseled chest and washboard abs displayed prominently in The Good, The Bad, and The Weird made me feel about my unforgiving pathetic male body. Yet even though the beauty of Bae's angles and curves are part of the aesthetics of Air Doll, this is not the porn of mainstream movie undress. Bae brings a depth to this aspirated body's role that could have popped with failure had it not been for her and Kore-eda's talents.

Ironically, Bae's role in Air Doll runs counter to what I and some other critics have appreciated about Bae, her willingness to go against the glamour imposed upon and pursued by many actresses (Korean or otherwise) and instead play roles where the characters are plain and not beautiful, at least not within the mainstream constructs of beauty. Watch her in Barking Dogs Never Bite and Linda, Linda, Linda and you don't see the doll that Bae becomes here. In Air Doll, Bae's beauty and Bae's body are on full display. Bae is an actress comfortable in her own skin, a good thing because she's in only her skin a lot in Air Doll. This constant nakedness of her indeed beautiful body might perpetuate the media-imposed feelings of inadequacy about one's body for some women as Lee Byung-heon's chiseled chest and washboard abs displayed prominently in The Good, The Bad, and The Weird made me feel about my unforgiving pathetic male body. Yet even though the beauty of Bae's angles and curves are part of the aesthetics of Air Doll, this is not the porn of mainstream movie undress. Bae brings a depth to this aspirated body's role that could have popped with failure had it not been for her and Kore-eda's talents.

Air Doll begins by acknowledging the creepiness of the topic, where we follow home a man named Hideo where we are lead to believe he is greeting his wife Nozomi. We quickly discover his wife is in fact a blow-up doll. (There is a non-diegetic creepiness to this for Japanese audiences, since the actor playing Hideo is Itao Itsuji, a comedian who was unable to find work for a while due to his own sex scandals plastered across the tabloids.) The next morning Nozomi takes on life in the form of Bae's naked form. Nozumi's discovery of her embodiment is much of what propels the film, be it the remnants of melded plastic that outline her body, or how others perceive her 'body', such as a child's frightened response to Nozumi's surprisingly cold temperature. Nozomi's discovery of life and living works because of Bae's perfectly stammered walking of the line between childish innocence and an adult awareness of, if not mortality, her vulnerability in being a being of air-encased form. The vulnerability reveals itself in one of the most creatively erotic scenes in cinema, a verisimilitude of an orgasm as never seen on screen before. The juxtaposition of fear and joy that this scene heightens will be tonally flipped in a later scene, revealing the horror that peeks through occasionally in Kore-eda's work.

In fact, the horror here appears cyclically throughout Air Doll, from the beginning of Hideo's strange relationship with the blow-up doll, to the rape scene of a limp live Nozomi when her dual-life is exploited by her boss. (This latter scene reveals the reason behind what begins as a conceit, wondering how she could possibly get a job at a video store.) In many ways, Kore-eda and Goda Yoshiie, the creator of the manga upon which this film was partially based, are demonstrating the perversion and harm caused when disconnecting from others through objectification. Ironically, this is brought to light by bringing to life a non-human object rather than dehumanizing a human object. Yet equally disturbing is how Nozomi's innocence causes the horror of a later scene. Dressing someone up, metaphorically, if not literally, in french maid and baby doll costumes, can come back to haunt you indeed.

In the end, this is a film for all the lonely people. Another aspect of Bae's work that impressed Kore-eda is that Bae had to convey her character's sadness without the signifiers of tears, since her character's body would be unable to produce them. Bae's character connects with the sadness surrounding her, from the middle-aged woman who finds herself treated differently because she is no longer young, to the young hikikomori, the phenomenon of individuals in Japan who act as hermits in their own apartments, rarely leaving if only for food, piling up trash in their rooms to further wall themselves off from the outside world. (Bong Joon-ho explored this contemporary mental illness in Japan for his contribution to the omnibus film Tokyo!.) Yet this embrace of the lonely does not completely excuse their own responsibility in their condition. Hideo's rather didactic (in English) dialogue demands that Nozumi go back to mute doll-hood and Nozumi's comatose response to a rape in the film keeps the depictions of loneliness from being saccharine and innocent. It is a complicated loneliness brought about by individuals with particular options for agency within an ever atomizing world.

All of this is brought to life by one of South Korea's greatest contemporary actresses in a role within a film by one of Japan's greatest contemporary directors. Or better yet, Air Doll exemplifies what can be accomplished when two universal talents come together to make a universal film. (Adam Hartzell)

Yang Yong-hi's film Our Homeland, which I saw at the 2013 San Francisco International Film Festival, is a heart-wrenching tale of unresolved family tensions that are tightened up even further in zainichi Korean politics. For those unfamiliar with zainichi, let alone the politics, that is where we must begin.

Zainichi is Japanese for 'residing in Japan' and it implies '(foreigner) residing in Japan'. Zainichi can be Taiwanese, Iranian, etc., but the zainichi we are talking about here are zainichi Korean. (For the rest of this review, I am going to follow the tradition of scholarly literature and just write "zainichi" instead of "zainichi Korean".) The reason there are a significant number of Koreans living in Japan is due to Japan's 35-year colonization of Korea from 1910-1945 when many Koreans were forced to migrate to Japan. During this time, many zainichi were connected with the Korean Independence Movement and when Japan surrendered, many returned to Korea. Still, a significant number stayed in Japan but maintained ties with their homeland. When their homeland split during the Korean War, the expectation arose for zainichi to state with which Korea they held their homeland allegiances. The majority stated their allegiances with North Korea. As a result, since zainichi are not considered full Japanese citizens unless they naturalize, their Japanese passports state this allegiance as well. Due to Japanese ideologies of pure blood nationality, zainichi have experienced discrimination in housing, employment, and social settings. Many first-generation zainichi continue to maintain ties to their chosen Chosun and while in Japan they maintain and advocate for a separate school system. But as David Chapman notes in his engaging overview of changing zainichi Korean identity, Zainichi Korean Identity and Ethnicity (Routledge, 2008), an alternate identity began to emerge for the second- and third-generations around the time of the Hitachi employment discrimination case (Hitachi shushoku subetsu saiban) which Pak Chong-sok won in 1974. In their view, Japan was their home and where they belonged. They would not deny their ethnic difference anymore than they would deny that they lived and belonged in Japan. This new zainichi identity, along with Burakumin (Japan's 'untouchables' caste), Ainu (indigenous peoples of Hokkaido), and other oppressed groups in Japan, contributed to developing a Japanese-specific multiculturalism. With different takes on identity across generations, some political tensions exist between younger and older zainichi. To quote David Chapman, "The social construction of zainichi identity is influenced by the zainichi population as well as the Japanese state" (p 143).

Zainichi is Japanese for 'residing in Japan' and it implies '(foreigner) residing in Japan'. Zainichi can be Taiwanese, Iranian, etc., but the zainichi we are talking about here are zainichi Korean. (For the rest of this review, I am going to follow the tradition of scholarly literature and just write "zainichi" instead of "zainichi Korean".) The reason there are a significant number of Koreans living in Japan is due to Japan's 35-year colonization of Korea from 1910-1945 when many Koreans were forced to migrate to Japan. During this time, many zainichi were connected with the Korean Independence Movement and when Japan surrendered, many returned to Korea. Still, a significant number stayed in Japan but maintained ties with their homeland. When their homeland split during the Korean War, the expectation arose for zainichi to state with which Korea they held their homeland allegiances. The majority stated their allegiances with North Korea. As a result, since zainichi are not considered full Japanese citizens unless they naturalize, their Japanese passports state this allegiance as well. Due to Japanese ideologies of pure blood nationality, zainichi have experienced discrimination in housing, employment, and social settings. Many first-generation zainichi continue to maintain ties to their chosen Chosun and while in Japan they maintain and advocate for a separate school system. But as David Chapman notes in his engaging overview of changing zainichi Korean identity, Zainichi Korean Identity and Ethnicity (Routledge, 2008), an alternate identity began to emerge for the second- and third-generations around the time of the Hitachi employment discrimination case (Hitachi shushoku subetsu saiban) which Pak Chong-sok won in 1974. In their view, Japan was their home and where they belonged. They would not deny their ethnic difference anymore than they would deny that they lived and belonged in Japan. This new zainichi identity, along with Burakumin (Japan's 'untouchables' caste), Ainu (indigenous peoples of Hokkaido), and other oppressed groups in Japan, contributed to developing a Japanese-specific multiculturalism. With different takes on identity across generations, some political tensions exist between younger and older zainichi. To quote David Chapman, "The social construction of zainichi identity is influenced by the zainichi population as well as the Japanese state" (p 143).

This is the political background that helps make sense of some of what happens in Our Homeland. As a zainichi herself, Yang Yong-hi has based this story partly on her own family's history. In Our Homeland, we learn that a repatriated son (Sung-ho, played by Arata, whom many will recall from Kore-eda Hirokazu's excellent film After Life.) is returning from North Korea for a brief 3-month stay to undergo treatment for a brain tumor. He was repatriated when he was 16 and hasn't been to Japan since. The family patriarch had to utilize his position in a zainichi North Korean organization to coordinate this 'unofficial' visit by his son. Of course, his son is followed by a North Korean comrade who keeps his eyes and ears on Sung-ho as much as possible, much to the consternation of the independent spirit that is Rie, the daughter of the family who was never repatriated to North Korea, but who is constrained in other ways by her community, such as her father's demands that she only marry a North Korean-affiliated zainichi. (Ando Sakura is a joy to watch in this spirited role of Rie, deservedly winning the 2012 Blue Ribbon Best Actress Award. Arata won Best Supporting Actor as well and the film went on to win Best Screenplay and Best Picture.)

The decision to initially repatriate the son was instigated by the father and is tied up in unspoken mystery. Much of the tension of the film is what lies beneath words, such as the bargaining chip the son had to offer up to the North Korean government to secure this temporary visit. Intrigue surrounds this family as what is left unsaid is finally said, or at least hinted upon. The regret of repatriation simmers throughout the film, building gradually to an anguishing crescendo and a final decision by Rie that underscores the re-calibration of zainichi identity by her generation.

As a second-generation zainichi born in Osaka, Yang demonstrates a respectful yet unflinching focus on the political tensions within the zainichi community. This is her first feature, and the discrimination faced by zainichi in Japan is less on display here, although when Rie arranges a basement bar reunion with Sung-ho's old school friends, one of whom is gay, discussion of being a 'minority within a minority' occurs and Sung-ho is credited with being one of the few folks who was kind to the outcast's outcast. Yang's other two films are documentaries about her family in North Korea, Dear Pyongyang (2005) and Sona, the Other Myself (2010). After making these two documentaries and stating forthrightly her criticisms of North Korea, Yang was eventually banned from North Korea. She still plans to make films about her family in spite of this trouble and in spite of her concerns for the safety of her family in North Korea. As Our Homeland underscores, it is the unsaid that can often lead us to decisions that we regret years later. It appears from Yang's documentaries and this first feature that she is dedicated to not regretting, for she refuses to stay silent in the face of discomforting politics, be they global or personal. (Adam Hartzell)

(Note: this review has been temporarily placed on this page only because we do not have a separate page for reviews of North Korean films. If such a page is ever launched in the future, we will move it then.)

North Korean-Belgian-UK co-productions are a rarity in today's world. North Korea's state-controlled film industry does not often partner up with foreign partners to make films for local audiences or for export. But it does happen occasionally: examples include the North Korean-Japanese co-production Somi - The Taekwondo Woman (1997) and North Korean-Chinese co-production The Secret of Rikidozan (2005). Comrade Kim Goes Flying is a somewhat unique case. Nicholas Bonner, originally from the UK, has been living in Beijing since 1993, running Koryo Tours which organizes various kinds of cultural exchanges with North Korea. In recent years he has partnered with director Daniel Gordon to shoot a series of acclaimed documentaries in North Korea, including The Game of Their Lives (2002), A State of Mind (2004), and Crossing the Line (2006). These works have become well-known in North Korea, as well as internationally.

North Korean-Belgian-UK co-productions are a rarity in today's world. North Korea's state-controlled film industry does not often partner up with foreign partners to make films for local audiences or for export. But it does happen occasionally: examples include the North Korean-Japanese co-production Somi - The Taekwondo Woman (1997) and North Korean-Chinese co-production The Secret of Rikidozan (2005). Comrade Kim Goes Flying is a somewhat unique case. Nicholas Bonner, originally from the UK, has been living in Beijing since 1993, running Koryo Tours which organizes various kinds of cultural exchanges with North Korea. In recent years he has partnered with director Daniel Gordon to shoot a series of acclaimed documentaries in North Korea, including The Game of Their Lives (2002), A State of Mind (2004), and Crossing the Line (2006). These works have become well-known in North Korea, as well as internationally.

The idea for Comrade Kim Goes Flying was developed by Bonner and Belgian producer Anja Daelemans in 2006, and was originally conceived as a short film. After sharing the idea with North Korean producer Ryom Mi-hwa, with whom Bonner had collaborated on his documentaries, two North Korean screenwriters began working on a script. Although the story was originally rejected by the state-run film studios as "too unrealistic," Ryom was eventually able to get the film approved after numerous rewrites and after receiving the support of director Kim Gwang-hun, who is established as a director of "military films." Comrade Kim was shot with three directors, and two acrobats from the Pyongyang Circus in the lead roles. It then underwent postproduction in China and Belgium, giving it a glossy sheen that ordinary North Korean films lack.

The story centers around Kim Yong-mi, a young woman from the provinces who works in a coal mine, but who dreams of becoming a trapeze artist. When she is given a year-long assignment to work on a construction project in Pyongyang, she steals off to the Pyongyang Circus and manages to meet her childhood hero, the famous trapeze artist Ri Su-yon. Ri encourages her to audition for the Circus, but without any previous training, she humiliates herself. The arrogant trapeze star Pak Jang-phil mocks her, telling her that coal miners belong underground, not in the air. But Yong-mi is not one to give up easily.

Comrade Kim Goes Flying provides a memorable viewing experience. The 81-minute film contains an inside look at North Korea which certainly does not reflect the realistic, everyday experiences of its citizens, but which is fascinating nonetheless. Lead actress Han Jong-sim, who had no acting experience prior to taking this role, has an upbeat charisma that is infectious. As a film, it is genuinely entertaining. It is unlike most North Korean films in being centered around a single female protagonist whose dreams and ambitions are essentially personal. But in other respects, its North Korean screenwriters have given it a distinctly local feel.

Two difficult questions leap to mind while watching this film. The first is, is it "authentic?" In style it is not quite North Korean, and not quite Western. I couldn't help but ask myself if the film's kitschy charm was directed primarily at a North Korean or a Western audience. But it does seem to have struck a chord in North Korea after its general release in late 2012. While visiting the Udine Far East Film Festival in Italy, actress Han Jong-sim spoke of receiving fan mail from inspired viewers across the country. Also, the number of young girls auditioning for the Pyongyang Circus has reportedly shot up in the wake of the film's release. Given this, I think we should credit the film as being "authentically local."

The second question is, is it propaganda? In terms of its explicit content, the answer is no. At face value, it is a story of one woman's individual triumph. One might ask if the bright colors and the rosy view of North Korean life function as a kind of indirect, subliminal propaganda. (Though I think anyone asking this question should acknowledge that production companies and advertising agencies in the West are much more skilled at this sort of 'subliminal propaganda' than North Korean film studios ever will be.) Does Comrade Kim Goes Flying provide moral support to a dictatorial, highly oppressive regime? This may sound evasive, but I really do believe that viewers should watch this film and decide for themselves. (Darcy Paquet)

Before I go in, I am going to warn you that this review contains one or two spoilers about the original Oldboy. If you haven't watched the original and wants to remain in a pristine state of ignorance about one of the crazy-f*ck masterpieces of New Korean Cinema, then please don't proceed any further. Trust me, it's not worth getting spoiled out of this envious state of being, just so you can read about its vastly, massively inferior remake.

One of the hot Korean cinematic properties to be nabbed in late 2000s by Roy Lee and once attached to Justin Lin (The Fast and Furious films) and later Dreamworks with Steven Spielberg as the possible director, the Oldboy remake project then seemed to go out of steam and sputter to wheezing death as the new decade rolled in. However, to the surprise of many, the project was revived and offered to Spike Lee (Do The Right Thing), put in charge of a reasonably decent cast: Josh Brolin (Milk) as the American version of Oh Dae-soo, Sharlto Copley (District 9) in the Lee Woo-jin role and Elizabeth Olsen (Martha Marcy May Marlene) in the shoes of Gang Hye-jeong as Mido.

One of the hot Korean cinematic properties to be nabbed in late 2000s by Roy Lee and once attached to Justin Lin (The Fast and Furious films) and later Dreamworks with Steven Spielberg as the possible director, the Oldboy remake project then seemed to go out of steam and sputter to wheezing death as the new decade rolled in. However, to the surprise of many, the project was revived and offered to Spike Lee (Do The Right Thing), put in charge of a reasonably decent cast: Josh Brolin (Milk) as the American version of Oh Dae-soo, Sharlto Copley (District 9) in the Lee Woo-jin role and Elizabeth Olsen (Martha Marcy May Marlene) in the shoes of Gang Hye-jeong as Mido.

So how bad is it? Well, very bad. There is little doubt that this is one of the worst American remakes of Asian genre cinema I have seen: its underwhelming critical and box-office performance might actually help kill off the trend (and that would not be a bad thing at all). In fact, the new Oldboy not only is a lugubrious, pointlessly vicious clunker, almost entirely devoid of entertainment value and any artistic insight into the human condition, but also represents such a completely wrong-headed misconstrual of the original's unique qualities, that it becomes by default an almost perfect model example of what "Hollywood remakes don't get" about the Korean originals, not to mention the cinema of Park Chan-wook in particular.

Spike Lee, despite his reputation as a controversy-monger, had previously made more than a couple of good genre thrillers, notably Clockers (1995) and Inside Man (2006), so it wasn't exactly lack of talent that got him into this fiasco. To be fair, he was supposed to have disowned this theatrical-release cut, sheared of more than twenty minutes from his intended version, although to me the problem with the movie appears to lie deeper, in the way the project was conceived on the thematic level by Lee or his screenwriter Mark Protosevich (I Am Legend), than its structure or texture.

Lee's remake follows the original's plot closely with a minimum of creative adaptation. There is a bit more of the detail to the alcoholic misbehavior of Brolin's main protagonist, and an interesting take on the private jail as a kind of flea motel from Hell. On the other hand, Lee jacks up the violence quotient even higher than in the original. In Park's version, for instance, Oh Dae-soo tortures his jailer by performing amateur dental surgeries: here, Joe Doucette (Brolin) bloodily perforates the jailer's (Samuel L. Jackson, way too promiscuously choosing projects these days) neck with an X-Acto knife. The violence/action all quickly becomes impersonal, almost irritating, rather than flinch-inducingly dangerous or emotionally powerful: the original's notorious corridor-hammer single-take action sequence is pointlessly expanded to show more graphic bodily damage, but utterly lacking in wit, grace or excitement. The tone, comic-book bright and grandiloquently nutsoid in the original, is bleaker and more sullen, the entire film taking place in calculatedly dehumanized environments, be it the chrome-and-glass penthouse of Copley's villain or the arid, mock-chinoiserie flourish of the Chinatown streets (Lee also indulges in the borderline-ludicrous Dragon Lady fetishism but given many, many problems with this movie that is just a minor trifle).

Watching this remake, it is striking, too, how important the quasi-literary, bizarrely off-kilter ruminations by Choi Min-sik was to the original's sense of humor and twisted but intellectual cadences: Doucette in this movie is simply a massive hunk of muscle with little sense of irony or affectation, and it is hard to identify with him either as an anti-hero or as an everyman. Needless to say, his "romance" with the young case worker Marie (Olsen) is totally unconvincing, but neither actors can be faulted for being unable to do much with the critically underwritten roles they are saddled with.

But it is with the re-writing of the central relationship between Sharlto Copley's "villain" and Doucette as young men in Evergreen Academy that the film truly loses its bearings. It is difficult to talk about how this re-writing reshuffles and whitewashes character motivations of the original, without revealing some aspects of the original's final twist: suffice to say that the moral ambivalence and genuine sense of transgression attached to the original's incestuous relationships are totally wiped out in this remake: Copley's character is now simply a sick bastard, his relationship with his sister meaning less than zero: Doucette's "original sin" evaporates into nothingness in this reordered, American (sex-hating and male-centered) moral universe. All that remains is Lee's (or Protosevich's?) smirking derogation of the white class privilege, here equated with sexual perversity pure and simple. Instead of a thoughtless scoundrel who had driven a sensitive teenager to her death in the original, Oh/Doucette here is merely a callous rooster who happened to have inadvertently exposed the Biblical Abomination to the outside world. So there! Oldboy, vivisected, disemboweled and sewn together with new stuffing, is transformed into yet another A-Decent-White-Guy-against-the-Sicko-World movie, who gotta stick to Normal Sex on pain of losing his soul. Was this supposed to play well in Peoria?

When Robert L. Cagle and other film scholars inveigh against American critics, film producers and viewers for misunderstanding or dismissing without comprehending the moral philosophy behind Park Chan-wook's cinema and champion the latter's utter uniqueness, some might be tempted to retort, "Yeah well, there are Hollywood movies that do all that you claim Park's movies do." True enough. However, I must say that a case like the Oldboy remake does lend credence to Cagle and others' claims: Hollywood genuinely don't seem to get it. What make these Korean/Asian movies so uneasy, disturbing and yet haunting in the first place-- and these are not, by God, extreme violence, extreme misogyny, extreme sex and other Extreme Cinema claptrap-- are the first to be gutted and thrown away in the American remakes. The 2013 Oldboy illustrates this in an exemplary manner for all to see. (Kyu Hyun Kim)

Since late 2000s it has been more or less a foregone conclusion that one or more of the three Korean directors whose genre films have received much support not only among American film fans but also industry insiders- Park Chan-wook (Oldboy), Kim Ji-woon (A Tale of Two Sisters) and Bong Joon-ho (The Host)-- would take their projects to Hollywood, a la John Woo and Tsui Hark (Ang Lee's case is notably different). The only question was when and who first. As it turns out, Park and Kim almost simultaneously released their Hollywood-produced, English-language projects, a Hitchcockian thriller Stoker and an updated Western The Last Stand respectively, while Bong chose to mount a Korea-US-European co-production Snowpiercer based on a classic French SF comic, to open in time for the summer 2013 season.

Stoker takes place in a regionally unspecific (Southern? No actor employs Southern accents, however) American small town. India Stoker (pouty Mia Wasikowska, looking like a cross between Bae Doo-na and Lee Young-ae) has just turned eighteen. Her father (wonderful Durmot Mulorney, regrettably not around much) just died in a suspicious car accident. Feeling morose, she barely gets along with her neurotic mother Evelyn (the more harried-looking-than-usual Nicole Kidman) who seems alternately jealous of and patronizing toward her. Her father's funeral brings an unexpected element of chaos to the household in the person of Uncle Charlie (overly creepy Matthew Goode). His sexual allure and dangerous mind-games drive a wedge between India and Evelyn, but as Charlie keeps upping the ante, India becomes aware that he is not merely an unconventional, free spirit but a homicidal psychotic.

Stoker takes place in a regionally unspecific (Southern? No actor employs Southern accents, however) American small town. India Stoker (pouty Mia Wasikowska, looking like a cross between Bae Doo-na and Lee Young-ae) has just turned eighteen. Her father (wonderful Durmot Mulorney, regrettably not around much) just died in a suspicious car accident. Feeling morose, she barely gets along with her neurotic mother Evelyn (the more harried-looking-than-usual Nicole Kidman) who seems alternately jealous of and patronizing toward her. Her father's funeral brings an unexpected element of chaos to the household in the person of Uncle Charlie (overly creepy Matthew Goode). His sexual allure and dangerous mind-games drive a wedge between India and Evelyn, but as Charlie keeps upping the ante, India becomes aware that he is not merely an unconventional, free spirit but a homicidal psychotic.

Stoker's basic setup is reminiscent of Hitchcock's Shadow of a Doubt (1943), but after the blueprint of family relationship has been laid out, the film moves along with its own agenda. First thing first: it will not disappoint Park's fans who had been afraid that Hollywood might have "defanged" him. Stoker fully retains most of the elements you expect from a Park Chan-wook brand: dazzling mis-en-scene and stylistic touches, this time zeroing in on the shiver-inducingly sensual textures of human hair, paper, shavings of a sharpened pencil and other familiar materials: face-slapping reversal of the audience expectations in the moral and emotional behavior of the characters, which a longtime fan of Park's oeuvre almost anticipates with glee (in this film, a particular scene involving a nude character and a hot shower, qualifies-- the American viewers I have seen this film with responded to it either with a disbelieving bark of a laughter or a stunned silence): vistas of breathless sexual entanglement and horrifying violence, discomfiting in their seductive beauty coexisting with conceptual perversity of the first order.

Adding subtle flavors to the already exquisitely picante dish are contributions from the top Hollywood talents now at Park's disposal, aside from his old collaborator, the veteran DP Chung Chung-hoon (The Unjust, New World): production design by Therese DePrez and others, costumes and styling by Kurt and Bart (who did Britney Spears's "pop diva" look) and, most notably for me, the sneakily witty score by Clint Mansell (Darren Aronofsky's longtime musical partner), with no less luminary than Philip Glass slipping in a piano piece for a memorable duet performed by India and Charlie.

Yet, Stoker in the end feels more like a reined-in try-out than a full-fledged piece-- the kind of song a brilliant singer would prepare to use at an audition, rather than an actual performance-- especially after the masterful reinterpretation of the vampire myth in Thirst (2009). I cannot help feeling that there is something missing. Perhaps the fault lies with Wentworth Miller's screenplay: even though everyone speaks with the perfectly "normal" English, the script is bereft of the sometimes bizarrely "literary," uniquely dense dialogues found in Park's other Korean films. Likewise, I found Stoker's generic American community lacking in the colorful cultural hybridity of Seoul and other Korean cities, an important factor in creating the organic whole that is a Park Chan-wook film. I believe the Korean critics's insistence at regarding Park's films taking place in an artificial, non-realistic environment often renders them blind to the specificity and materiality (even Koreanness) of Park's films.

This curious sense of detachment, if not anonymity, is amplified at the film's denouement, in which India actively embraces her identity as a product of her family history, replete with the unacknowledged sins and insanity: "my father taught me... that you sometimes have to do a terrible thing to prevent you from doing something worse," she intones. But ultimately, this was not convincing. India seems to have just walked down the preordained path, rather than having truly grown as a character (which the young Charlie does experience in Shadow of a Doubt, although it is probably unfair to keep comparing Stoker to it). Perhaps I was not the only Park Chan-wook fan who missed the crisp yet richly meaningful exchange that ended Thirst.

By no means a failure, Stoker is impressive and alluring, obviously a work of a brilliant artist. However, having experienced the emotional devastation as well as pulverizing stimulation of senses provided by Park Chan-wook's previous movies (including even JSA and I'm Cyborg But That's OK), I cannot help but feeling a tiny bit disappointed that it is a work easier to admire than to love. (Kyu Hyun Kim)

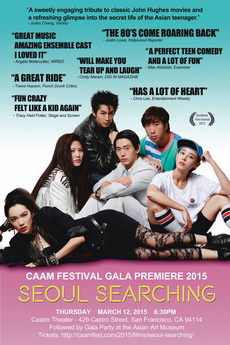

Director Benson Lee wrote his preliminary draft for what would become Seoul Searching just before the new millennium. This film about one summer in the short-lived tradition of annual South Korean summer camps for 'gyopo', (Koreans raised outside Korea), might have never been made were it not for the financial assistance of Chinese investors. Even when US distributors finally did take interest after the successful premiere screenings at Sundance, the offers weren't what director Lee feels the film was worth. As a result, Lee will be releasing the film on his own, working off local demand to determine release cities and dates. If you've been searching for a film such as this one, you will want to join their Facebook page and learn how to get this film to come near you, As for me, I thoroughly enjoyed watching this 80s remix at CAAMFest in the lovely Castro Theatre in San Francisco.

The year Seoul Searching takes place is 1986, when I was 16, the age of some of the characters on screen. The soundtrack is full of songs from my 80's. (OMD's "Forever Live and Die" accompanies the credits. Since the chorus is in my vocal range, I couldn't resist making this screening a sing-along at the end, the Castro Theatre my noraebang.) This makes me curious what percentage of the production costs went to securing music rights. But regardless how much, such costs did not result in Lee cutting any corners. This is a high quality production showing Lee is just as expert at crafting an engaging feature film as he was piecing together an enthralling narrative within his superb documentary Planet B-Boy (2007).

The year Seoul Searching takes place is 1986, when I was 16, the age of some of the characters on screen. The soundtrack is full of songs from my 80's. (OMD's "Forever Live and Die" accompanies the credits. Since the chorus is in my vocal range, I couldn't resist making this screening a sing-along at the end, the Castro Theatre my noraebang.) This makes me curious what percentage of the production costs went to securing music rights. But regardless how much, such costs did not result in Lee cutting any corners. This is a high quality production showing Lee is just as expert at crafting an engaging feature film as he was piecing together an enthralling narrative within his superb documentary Planet B-Boy (2007).

Lee does an excellent job of keeping a vast cast of characters going throughout the film. The diversity of gyopo experience in this film is part of what makes it so delightful. Lee was even able to cast, for the most part, actors who grew up in the same countries as their characters. There are American characters such as Sid the punk rocker played by Justin Chon (21 & Over & Revenge of the Green Dragons) and Grace Park the preacher's kid, Madonna-wannabe played by Jessica Van (upcoming TV series 'The Messengers' & 'Rush Hour'). Stepping away from the US, there is the German budding finance tycoon Klaus Kim played by Teo Yoo (German film Day Night Day Night and the Kim Ki-duk film One on One), the British Sara Han played by Sue Son ("Britain's Got Talent" 2007), and the Italian Marcello Ahn played by Yoon C. Joyce (Italian films The Mark & Se chiudi gli occhi). The only actor whose nationality is not in sync with his character is Mexican lothario Serge Kim, the debut role for Spaniard Esteban Ahn known across a segment of the Spanish-speaking internet for his "SanchoBeatz" YouTube series. In addition, he will soon be your new favorite actor because, as many have been saying, Ahn steals every scene he's in. His screen presence is truly infectious. The significant Korean actor cast is the teacher with a dark secret, Cha In-pyo (Crossing & The Flu). (Chon said his parents finally acknowledged him as an actor when they found out he would be working alongside Cha.) Although a small role, I was happy to see Crystal Kay playing the biracial character of Jamie since we too rarely see half-Black/half-Korean characters on screen, (former NFL star Hines Ward being the exception). Kay herself is African American and Korean. But she is also Japanese because she was born and raised in Japan, where she lives, records music in Japanese, and has been in a few Japanese movies (Giratina and the Sky Warrior & Yamagata Scream.)

There are clear references in Seoul Searching to the popular 80s oeuvre of John Hughes, right down to the promotional poster that is straight out of The Breakfast Club, just in time for the 30th anniversary of that Hughes' classic. As much as Hughes' films are said to define my generation, part of that definition was the racist caricature Hughes created in Long Duk Dong for Sixteen Candles (1984). Ask any Asian American man who grew up in the 80s, . . . actually, on second thought, don't ask them. They are tired of being reminded of the taunts of quotes from that movie. As Giant Robot magazine co-founder Martin Wong said to National Public Radio in the U.S., "Every single Asian dude who went to high school or junior high during the era of John Hughes movies was called 'Donger.'" Interestingly, Kirk Honeycutt recently revealed in Vanity Fair how Molly Ringwald, Ally Sheedy, and co-producer Michelle Manning took issue with a sexist scene in The Breakfast Club (1986) involving a synchronized swimming team. This scene was eventually cut. (Producer Ned Tanen axed a Russian janitor caricature played by Rick Moranis as well.). Sadly, no one on the earlier set of Sixteen Candles intervened to remove the Long Duk Dong character. So when CAAMFest Director Misashi Niwano called Seoul Searching a 'revision' of Asian America in the 80s, 'The Donger' character was clearly one of those 80s characters Seoul Searching discredits by showing actual Korean Americans (and Germans, Italians, etc) on an 80s screen. Seoul Searching revisits the 80s to remind us that Asian Americans existed, speaking in regional English accents, not in the racist accentuations voiced through Hughes' direction. In this way, Seoul Searching's could be a corrective for the harms Hughes caused on the playgrounds of the 80s.

There are many aspects of Seoul Searching I want to talk about in detail. There are aspects I want to praise and critique. But the film has yet to be released and the aspects of the plot I want to discuss can be considered spoilers. Let me speak cryptically then about one of the most moving scenes. Its impact is made stronger when ignorant of the Korean language because Lee chooses to not subtitle the scene. (It involves a tremendous performance played by Kim Ki-duk regular Park Ji-a.) And then Lee follows that scene later with parallel scenes of characters switching languages with a parent, demonstrating the intimacy that can be conveyed by a multilinguals language choice.

I will have to wait until after Seoul Searching has a significant theater run to discuss more. Considering that Benson Lee has been waiting 30 years to have this conversation, I figure I can wait six months or so.

Bring this movie to your town. Go see it with friends. Then we'll talk more later. (Adam Hartzell)

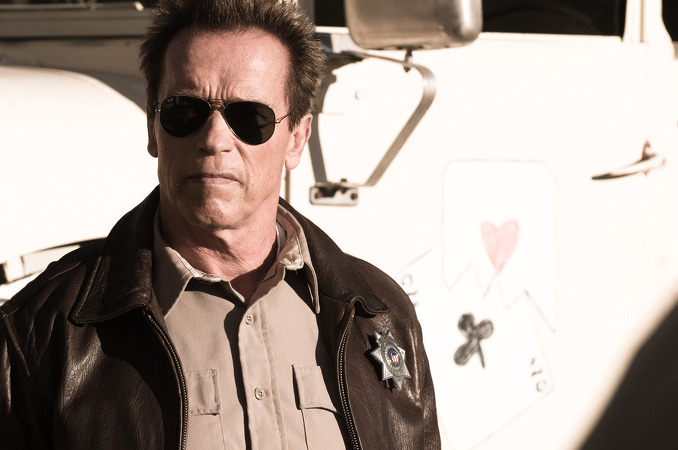

Just like I only went to see both Cloud Atlas and Jupiter Ascending because Bae Doona was in them, and how I plan to see Pixels because Peter Dinklage is in it and Trainwreck because of LeBron James, I wanted Paramount Pictures to know that I was only going to see Alan Taylor's Terminator Genisys because Lee Byung-hun was in it. So I did what the kids do these days. I tweeted them to make sure they knew. Forget Schwarzenegger. All profit from my roughly 15 dollar ticket should go to Lee. It's the least I could do considering he and his wife, actress Lee Min-jung, recently had their first child and I understand diapers are getting expensive.

And the reason this American film shows up in this section of Koreanfilm.org is also because only because of Lee, which will explain why I will deal very little with the plot here where characters from the future go back in time and then a little forward to our time to make sure John Conner still survives. Or something like that. Schwarzenegger gets to battle his old self in this one, which I'm sure fans of the franchise appreciate. But I'm not a fan of the franchise so it's not really going to thrill me. I think I fell asleep during the first one. (Or was that Robocop?) And I never saw the other two between this and that one. The Terminator franchise could terminate for all I care.

And the reason this American film shows up in this section of Koreanfilm.org is also because only because of Lee, which will explain why I will deal very little with the plot here where characters from the future go back in time and then a little forward to our time to make sure John Conner still survives. Or something like that. Schwarzenegger gets to battle his old self in this one, which I'm sure fans of the franchise appreciate. But I'm not a fan of the franchise so it's not really going to thrill me. I think I fell asleep during the first one. (Or was that Robocop?) And I never saw the other two between this and that one. The Terminator franchise could terminate for all I care.

Yet I do care about Lee's role here and his stoic, spartan performance is pretty awesome. Wikipedia says he's a T-1000 shape-shifting liquid metal Terminator if that means something to you. He takes on the human form of an LA cop. He has only one line. I guess Terminators aren't really supposed to talk when we know they are Terminators. As a result, Lee is all silent bad boy cool, wreaking mayhem early on in the film. He has moments where he wields silver knife like arms and those are visuals that stay with me as much as his early days of bungee jumping. Lee plays the type of bad guy you root for over the so-called good guys. I really wanted his scenes to continue throughout the film, but other shape shifters needed bodies to fill.

San Francisco has been getting destroyed in a lot of films these days. It's stomped and collapsed in recent installments of the Godzilla and Planet of the Apes franchises and even the California Academy of Science gets blown up in the mash-up of San Francisco and Tokyo that is Disney's Big Hero 6. Why people love to destroy my city, I don't know. It's almost like they want another earthquake to happen, a la San Andreas. But there has been an even more disturbing aspect of destroying San Francisco we find yet again in Terminator Genisys. That is the destruction through almost complete invisibility of the city's majority of citizens - Asian Americans.

Part of the plot of Dawn of the Planet of the Apes involves a virus that has devastated the human population of San Francisco. This virus apparently disproportionately impacts Asian Americans based on how few are in the film, even when scanning the extras. In the San Francisco of 2017 presented in Terminator Genisys, there is only one Asian American, and as a co-worker pointed out to me, (plot spoiler), she technically isn't real. But what about Lee, you ask? His character roams the streets of Los Angeles, not San Francisco. Interestingly, one blockbuster that does represent the Asian American majority of my fair city via three major characters is the animated one, Big Hero 6. Where these blockbusters fail, indie flicks prevail. The films of Dave Boyle, specifically Surrogate Valentine, Daylight Savings, and Man From Reno, do a much better job of representing San Francisco's diversity. (Full diclosure - I play an extra in Man From Reno and have a wide spectrum of relationships on the friendship-acquaintance scale with folks who have worked on Boyle's films.) I couldn't agree more with this statement from Boyle on a recent episode of the Way Too Indie podcast. "It seems like ... most of the San Francisco movies ... take advantage of the atmosphere and the kind of European vibe that the city has, but they don't actually delve into what life is actually like for people living in San Francisco."

In the case of Terminator Genisys they do make an effort to cast African Americans in non-stereotypical roles. It even appears as if they may have read Martin Kevorkian's book Color Monitors: The Black Face of Technology in America (Columbia University Press, 2008) that I discussed in my D-War review. Terminator 2: Judgment Day provides solid support for Kevorkian's thesis of black operators of technology positioned to protect white bodies from the contamination of technology. Here in Terminator Genisys the trope is reversed. The president of the technology company Genisys and his assistant (vice-president?) have a white guy touch the technology for them in a clear depiction of technological contamination.

And through this jettisoning of a prominent racial trope in science fiction, Terminator Genisys ironically shows that productions can make the effort to address problematic aspects of narratives in cinema. Any excuses that a fictional San Francisco cannot represent the factual majority Asian American population is that, just an excuse. Actually, it's more than that, it's a lazy excuse. If they were as half-ass in their CGI depiction of the Golden Gate Bridge, there would be an uproar on social media. Further irony on this film's erasure of San Francisco's Asian Americans - (where are the Latinos too, by the way?) - is that it prominently features Lee Byung-hun. Plus Schwarzenegger was a two-term governor of California. You would think he'd know about the demographics of the fourth largest city in the state he served for eight years and he'd express concern about the city's representation. Now if we can only make it so that irony is not lost on Hollywood. If I were a Terminator, I'd go back to disrupt these white-washing casting decisions. Sarah Conner can clearly take care of herself anyway. (Adam Hartzell)

At this moment in gay history in the US, much emphasis is made on 'coming out', enunciating one's queerness verbally to family, friends and co-workers. C. Winter Han suggests caution with this gay orthodoxy. In his book Geisha of a Different Kind: Race and Sexuality in Gaysian America (New York University Press, 2015), Han notes,

Because [Asian American] families often offer a source of social support that helps buffer the racism they encounter on a daily basis, simply coming out of the closet and joining the gay mainstream may not be an option that gay Asian American men view as being attractive if it means having to give up ties to their ethnic communities (p 182).

Because [Asian American] families often offer a source of social support that helps buffer the racism they encounter on a daily basis, simply coming out of the closet and joining the gay mainstream may not be an option that gay Asian American men view as being attractive if it means having to give up ties to their ethnic communities (p 182).

The problem with expectations of coming out imposed on queer people of color is that if coming out disrupts the cohesion of one's minority community, it is not as if the wider gay community will be fully accepting. The wider white gay community is just as prone to racism as the wider white non-gay community. Sample some of the profiles on the virtual cruising app Grindr and you will see 'No Asians' racism displayed as casually as 'No Mexicans' racism at a Trump Rally. The possibility of ostracism from one's ethnic community after verbally 'coming out' means one risks being severed from the community that can offer refuge when experiencing racism. A white gay person might also face ostracism when coming out, but they can find a queer community that still privileges their whiteness. Also, one can signify one's queerness in other silent ways. And one's family can send similar subtle signals of support. (Check out Benjamin Law's autobiographical TV series The Family Law where this everyone-knows-without-saying-it is lovingly, and hilariously, demonstrated within the context of a supportive Chinese Australian family, particularly episode 5, "Everything's Coming Up Roses".) An intersectional approach to identity is important in understanding what full choices individuals truly have. Choices come with different consequences for different groups. Part of what is so refreshing about Andrew Ahn's debut film Spa Night is that it displays this intersectional awareness so often ignored in films catering to a mainstream audience, even a mainstream gay one. Spa Night is not a coming out story. Spa Night presents a fully-realized individual who is a work in progress. It considers the intersectional layers of reconciling multiple identities, being Gay and Korean and American and Christian. David, (played in a wonderfully subdued manner by Joe Seo), doesn't want to jettison one of those identities to privilege another.

David's six pack selfies in the mirror of his bathroom is another aspect of Spa Night that recent scholarship on Asian American gay identity can help us unpack in many ways. We might too easily toss this aside as evidence of narcism, but it is clearly a source of sincere pride for David. Of all the things David can't control about his life, he is able to control how his body looks. It isn't clear if David is sharing these images on websites like Grindr, but the taking of headless naked torso shots features prominently on gay dating sites. Nguyen Tan Hoang closes his book A View from the Bottom: Asian American Masculinity and Sexual Representation (Duke University Press, 2014) by interrogating headless torso images posted by gay Asian men, ". . .They constitute a tactic that simultaneously contests and reaffirms the dominance of whiteness and the marginalization of Asianness in gay male communities" (p 200). David is meeting the expectations of mainstream gay desire by displaying his chiseled abs, but his refusal to show his face hides his Asianness. When Korean American drag queen Kim Chi affirmatively performed "Femme, Fat, & Asian" on the reality TV show RuPaul's Drag Race, he was confronting the three aesthetics disparaged in the mainstream gay community. Nguyen's scholarship reveals that David's selfies are ripe with paradox. They can express narcissism and confidence, they can be constraining and liberating, all in the same shot. (And we could go on and on with Lacan about taking selfies in the mirror, couldn't we?).

Ahn has said in interviews and post-screening Q&As that the inspiration for this film was a gay friend of his mentioning to Ahn that he once got an awesome handjob at a Korean spa. This shocked Ahn because his frame of reference was Korean spas were spaces for families, not orgasms. Ahn utilizes the fog of steam rooms, the Ozu-esque POV of on the floor camera angles, to surreptitiously hint at what is happening in the spas when hetero gazes aren't looking. In solidarity of desire, David offers assistance for cruising customer consummation while still presenting a hesitancy to participate himself. Much of the power of Spa Night is the cautious pace. David doesn't rush in, he prepares before submerging into the hedonistic bath that surrounds him. He savors the visual, haptic pleasures, well before reaching out and engaging in the tactile pleasures so close, yet so far from his reach. More time is spent in this secret sexual economy, much of which happens behind the closed steam rooms doors, but this secret society rhymes with the earlier hidden proceedings that led to the closing of David's parents' restaurant that we weren't permitted to witness earlier.

Ahn refuses an easy resolution in Spa Night. He's not letting the audience off the hook by providing them with final frame fulfillment. We have to sit in the sauna's oppressive environment, find ourselves slightly suffocating as we struggle to inhale. We have to hold all of David's layers, layers applied like rivers of sweat on our skins. We have to carry David's burden with us as we leave the theater. Spa Night does what I want cinema to do - it lives and breathes beyond the screen. (Adam Hartzell)

It is an alternative earth, year 2007. The platinum-blonde CEO of the global conglomerate Mirando Corporation, Lucy (Tilda Swinton), unveils her ambitious plan to introduce to the worldwide consumers the next generation of genetically engineered super-pigs. The most adorable yet meaty piglets picked out of the first litter have been distributed among twenty-six farms throughout the world, from whom one will eventually be selected as the winner during a massive publicity event to be held in New York City. Flash forward to 2017, deep in the mountains of the Gangwon Province, Korea: the super-piglet has grown into an enormous, SUV-sized sow with floppy dog ears and hippo-like maw, affectionately named Ok-ja by her caretakers, twelve-year-old Mi-ja (Ahn Seo-hyun, Monster) and her grandfather Hee-bong (Byun Hee-bong, The Host). Mi-ja's life with the grandfather and Ok-ja is rough but idyllic. Unfortunately, the Mirando Corporation intrudes into their lives, led by their PR front-man Johnny Wilcox (Jake Gyllenhaal), a former nature-documentary program host now gone to seeds, quickly declaring Ok-ja the winner of the contest and shipping her to New York. Aghast at her grandfather's betrayal, Mi-ja bravely follows Ok-ja's trail to Seoul, but is intercepted by a group of hooded young men and women claiming to be members of the Animal Liberation Front. The latter's leader, Jay (Paul Dano), attempts to convince her that Ok-ja should be enlisted in exposing Mirando's hideous animal rights abuse records. Meanwhile, Lucy's ruthless twin sister Nancy (Swinton again) working with a suave corporate shark Dawson (Giancarlo Esposito) plans to chuck the former's "sentimental" publicity stunt and send Mi-ja's animal friend to the industrial abattoir as soon as she could. Will our intrepid pre-teen heroine be able to save Ok-ja from becoming packets of processed pork, caught as she is between Mirando and the ALF, neither of which may have the best intentions for the lovely super-pig at their hearts?

Bong Joon-ho's (Snowpiercer) sixth feature film courted much controversy since its inception in 2015 when Brad Pitt's Plan B Production and the video rental/streaming giant Netflix came on board as its production company and worldwide distributor, respectively. The production budget estimated at approximately 50 million dollars, Okja is not a blockbuster production by the U.S. standard, but Netflix's decision to simultaneously release it online and in select theaters in South Korea has rubbed the theater-chain giant CGV wrong way, who, along with CJ, Lotte, Megabox and other domestic distributors resolved to boycott the film. Consequently, despite the explosive anticipation regarding the film as well as Bong's proven track records as one of Korea's biggest hit-makers, Okja was shown at only 111 screens as opposed to 1,000 and upward number of screens usually reserved for such a highly anticipated production (for a comparison, The Transformers: The Last Knight opened in 1,739 screens in its opening week). The good news is that, for a week of its initial run in the theaters, Okja scored very impressive 42 to 56 per-cent attendance rates (again, for a comparison, The Tranformers in its second week is scoring approximately 24 per-cent), boosted by excellent words of mouth. We can tentatively conclude that Okja's availability through a VOD streaming service has done little to dampen the enthusiasm among South Korean movie fans to catch Bong's latest projected on the big screen.

Bong Joon-ho's (Snowpiercer) sixth feature film courted much controversy since its inception in 2015 when Brad Pitt's Plan B Production and the video rental/streaming giant Netflix came on board as its production company and worldwide distributor, respectively. The production budget estimated at approximately 50 million dollars, Okja is not a blockbuster production by the U.S. standard, but Netflix's decision to simultaneously release it online and in select theaters in South Korea has rubbed the theater-chain giant CGV wrong way, who, along with CJ, Lotte, Megabox and other domestic distributors resolved to boycott the film. Consequently, despite the explosive anticipation regarding the film as well as Bong's proven track records as one of Korea's biggest hit-makers, Okja was shown at only 111 screens as opposed to 1,000 and upward number of screens usually reserved for such a highly anticipated production (for a comparison, The Transformers: The Last Knight opened in 1,739 screens in its opening week). The good news is that, for a week of its initial run in the theaters, Okja scored very impressive 42 to 56 per-cent attendance rates (again, for a comparison, The Tranformers in its second week is scoring approximately 24 per-cent), boosted by excellent words of mouth. We can tentatively conclude that Okja's availability through a VOD streaming service has done little to dampen the enthusiasm among South Korean movie fans to catch Bong's latest projected on the big screen.

The movie itself certainly does not disappoint the director's domestic and foreign fan base. It draws upon some familiar themes and motifs found in his previous works (the audacious mingling of a gargantuan CGI beast and live actors as in The Host; a young girl fighting to protect animals from heartless human predators/abusers as in Barking Dogs Never Bite; and so on), and non-coyly attributes homages to the sources as diverse (and wacky) as My Neighbor Totoro, Chaplin's Modern Times, George Franju's Le Sang de bête and the long-running Korean TV series Animal Farm. Like Bong's other films, Okja maintains a remarkably steady tone throughout its running time, never quite deciding to become an out-and-out dark satire, nor a para-Disney fable for contemporary adults, nor a Dark Knight-like urban action film with jaw-droppingly creative stunts, while incorporating into itself elements of all of these. As was the case with Snowpiercer, some viewers might feel nicked by Bong's refusal to smooth out sharp edges of his film in the manner of Hollywood blockbuster productions: he pulls no punches, for instance, from displaying the nightmarish vista of Mirando's meat processing plant. Others might take issue with the film's ambivalent message, as it were, as the Animal Liberation Front, led by the serenely self-absorbed Paul Dano, are not exactly portrayed as good guys. There is a giddy but disturbing undercurrent of obsessive zeal in their behaviors that serves as a counterpoint to the frazzled paranoia of the Mirando executives (One of the film's most intriguing sidebar plots involves serious consequences of the linguistic miscommunication between Mi-ja and her so-called allies, based on the Korean-American member K's [The Walking Dead's Steven Yeun] deliberate misinterpretation of a key dialogue from Korean to English).

The technical aspects are top-notch, as one would expect from a Bong Joon-ho film. Darius Khondji's (The Immigrant, Amour) cinematography is pure magic, contrasting misty yet intimate splendor of the Gangwon Province mountain-scape to the aggressive golds and blues of the concrete- and steel-bound NYC. In other departments, South Korean and U.S. talents collaborate seamlessly to weave together the flamboyant tapestry of clashing cultures-- Kevin Thompson (Birdman) and Lee Ha-jun's (The Thieves) production design stuffs the viewer's field of vision with glittering and gluttonous details, while Choi Se-yeon (Coinlocker Girl) and Catherine George (Jane Got a Gun) run with the visions of Swinton swathed in a cream-colored hanbok dress and Dano in a natty bell-boy uniform. The CGI effects employed to render Okja realistically "alive," supervised by Eric De Boer (Life of Pi) and other artists, are superior by leaps and bounds to those used to portray the amphibian beastie in The Host; I almost felt that Bong was using the early portions of his motion picture as a demo reel for the technical prowess of his effects crew.

The performances are equally intriguing but perhaps more likely to split the viewer opinions, especially among the American constituency. Ron Johnson's English dialogues (Having worked on, along with Mr. Editor, translation of the original Korean-language screenplay of Snowpiercer, I would love to find out how the English and Korean language division of labor was determined for Okja: one thing I can be sure is that no detail, however small, would have escaped Bong's eyes or ears) are a tad overtly satirical, and I wish Gyllenhaal's animal-show host had been more fully developed as a character (By the way, I do not find Gyllenhaal's alleged "overacting" a serious problem; his performance-- like Swinton's-- is fascinating in the sense that its pitch is held at the level that would be considered "normal" for a Korean actor, say, Hwang Jung-min or Yu Hae-jin, in a genre film of this type). On the other hand, Ahn Seo-hyun is perfect, an action-figure kokeshi doll with huge, soulful eyes, who nonetheless works beautifully together with a CGI creature and stands her ground against the teeth-baring Swinton in her scariest black-witch mode.

Okja is nothing if not adventurous; it has its shares of grotesqueries and black humor threatening to veer off into bad taste, along with the scenes of lyrical, heart-stopping beauty and thought-provoking poignancy. The film also refuses to pander to either the superficial breast-beating of American political satires or the self-importantly loud barking of the South Korean leftist social criticism directed at "neoliberal capitalism" but has little real bite in terms of actually challenging the complacency of the (Korean) hands that feed them. During the startling climactic confrontation between Mi-ja and Nancy Mirando, the Korean girl speaks a sentence of English dialogue that not only satisfactorily resolves the Gordian knot of the film's plot, but also cuts to the very core of the workings of the global capitalist system, exposing to us its monstrous, circular logic that feeds on itself like an Ouroboros worm. Heady stuff, this is; it is not something you will ever get to see in a Marvel superhero franchise film. In the end, Okja is truly a parable for our times. As I'm a Cyborg But That's OK was supposedly for Park Chan-wook, it might have been intended as a "breather" for Bong after making such "serious" works as Mother and Snowpiercer, but it will be your loss if you are fooled by its fairy-tale imprimatur and miss such an intelligent yet powerful critique of the crazy "real" world we live in. (Kyu Hyun Kim)