2000

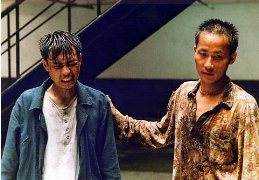

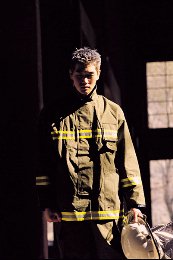

From left: "Lies", "Virgin Stripped Bare by her Bachelors", "Joint Security Area", "The Foul King"

In terms of box-office, the year 2000 proved to be almost as successful as the groundbreaking 1999. As with last year, a North-Korean themed work dominated the theaters, with Park Chan-wook's Joint Security Area setting attendance records and placing itself in line to become the best-selling Korean film in history (as of year-end it will remain in second place just behind Shiri, however it is forecast to pass Kang Je-gyu's film in early January). The success of this film has also brought its distributor, CJ Entertainment, into the elite status once held solely by local distributor Cinema Service.

With the release of a string of blockbusters including Bichunmoo, Libera Me and The Legend of Gingko, Korean cinema has now entered the high-priced market of big budget genre films. Although many of these blockbusters have drawn large numbers of viewers, high production costs means that film companies will likely need to sell these films abroad as well to turn a profit. Early returns indicate that there is growing interest in Korean films particularly in Asia, with Japan being the most important market.

Apart from box-office fare there was an unusually strong collection of art films released in 2000. Notable works include Peppermint Candy, Lies, Chunhyang, Barking Dogs Never Bite, The Isle, The Virgin Stripped Bare by her Bachelors, Die Bad, and Bongja. Korea also continues to churn out scores of fascinating, high-quality short films.

Reviewed below: Peppermint Candy (Jan 1) -- Lies (Jan 8) -- Chunhyang (Jan 29) -- The Foul King (Feb 4) -- Barking Dogs Never Bite (Feb 19) -- Interview (Apr 1) -- The Isle (Apr 22) -- Virgin Stripped Bare by her Bachelors (May 27) -- Ditto (May 27) -- Secret Tears (Jun 3) -- Bichunmoo (Jul 1) -- Die Bad (Jul 15) -- Nightmare (Jul 29) -- Joint Security Area (Sep 9) -- Il Mare (Sep 9) -- Pisces (Oct 21) -- Libera Me (Nov 11) -- Asako in Ruby Shoes (Dec 9).

| Korean Films | Seoul Admissions | Release Date | Weeks | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Joint Security Area | 2,499,400** | Sep 9 | 20* |

| 2 | The Foul King | 817,000 | Feb 4 | 12 |

| 3 | Bichunmoo | 730,300 | Jul 1 | 7 |

| 4 | The Legend of Gingko | 637,000 | Nov 11 | 6 |

| 5 | Libera Me | 546,300 | Nov 11 | 6 |

| 6 | A Nightmare | 332,000 | Jul 29 | 5 |

| 7 | Ditto | 326,000 | May 27 | 10 |

| 8 | Lies | 314,500 | Jan 8 | 5 |

| 9 | Peppermint Candy | 311,000 | Jan 1 | 11 |

| 10 | Jakarta | 282,200 | Dec 30 | 5* |

| All Films | Seoul Admissions | Release Date | Weeks | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Joint Security Area (Korea) | 2,499,400** | Sep 9 | 20* |

| 2 | Mission: Impossible 2 (US) | 1,130,000 | Jun 17 | 8 |

| 3 | Gladiator (US) | 1,127,000 | Jun 3 | 13 |

| 4 | The Foul King (Korea) | 817,000 | Feb 4 | 12 |

| 5 | Bichunmoo (Korea) | 730,300 | Jul 1 | 7 |

| 6 | The Legend of Gingko (Korea) | 637,000 | Nov 11 | 6 |

| 7 | Dinosaur (US) | 619,000 | July 15 | 6 |

| 8 | The Perfect Storm (US) | 572,000 | Jul 29 | 5 |

| 9 | Libera Me (Korea) | 546,300 | Nov 11 | 6 |

| 10 | Charlie's Angels (US) | 487,000 | Nov 25 | 5 |

* Includes tickets sold in 2001.

** Joint Security Area drew an estimated 5.8 million admissions nationwide.

Market share: Korean 35.1%, Imports 64.9% (nationwide)

Films released: Korean 59, Imported 342

Total attendance: 64.6m admissions

Number of screens: 720 (nationwide)

Exchange rate (2000): 1139 won/US dollar

Average ticket price: 5,355 won (=US$4.70)

Exports to other countries: US$7,053,745

Average budget: 1.5bn won + 0.65bn p&a costs

Source: Korean Film Council (KOFIC).

Short Reviews

These are some reviews of the features released in 2000 that have generated the most discussion and interest among film critics and/or the general public. They are listed in the order of their release.

As one of the most anticipated films of the year, Peppermint Candy, the second feature from acclaimed director Lee Chang-dong, was chosen to be the opening film of the 1999 Pusan International Film Festival. Some people viewed this as a coming of age: both for Lee, the novelist-turned-director whose debut feature Green Fish (1997) took home the top prize from the Vancouver International Film Festival; and for Korean cinema in general, since this was the first time in PIFF's four-year history that a domestic film was chosen for this honor.

The festival opened with fireworks, speeches, and a bit of rain, and when the film began to roll it clashed somewhat with the festive atmosphere. Peppermint Candy is the personal history of a man whose troubled experiences leave him greatly disturbed. The film asks of its viewers a fair amount of concentration and emotional energy; some scenes are upsetting, while others give us mere hints of beauty: the undeveloped potential that lies dormant within our hero.

The festival opened with fireworks, speeches, and a bit of rain, and when the film began to roll it clashed somewhat with the festive atmosphere. Peppermint Candy is the personal history of a man whose troubled experiences leave him greatly disturbed. The film asks of its viewers a fair amount of concentration and emotional energy; some scenes are upsetting, while others give us mere hints of beauty: the undeveloped potential that lies dormant within our hero.

The narrative structure of Peppermint Candy shares much in common with an early Jane Campion film, Two Friends, in that we first witness a tragedy, and then progress backwards in time to learn the events which led up to it. The film contains seven episodes from our hero's life, each of which reveal him in a different stage of development. These segments are linked by a series of shots taken from the back of a train, as if to suggest that the train itself leads us back into his past.

Many of the episodes in our hero's life echo the contemporary history of Korea: serving in the military, torturing political dissidents as a policeman, and losing money in a failed business venture. These symbolic events mingle with the personal aspects of his life: an early love affair, which continues to haunt him years later, and his subsequent failed marriage.

Ultimately the main character remains out of our grasp. Lee denies us any easy explanations for our hero's character, or excuses for his behavior. The film frustrated me as I was watching it for the first time; I wanted greater access to the hero's feelings. Nonetheless, I felt shattered upon reaching the end of the film, and it has beckoned me back for a second viewing. (Darcy Paquet)

On January 8, 2000, after months of rejections and punitive delays by the ratings board, the latest feature by Jang Sun-woo finally reached the theaters. With a scalped ticket in hand, I pushed my way past the crowds and TV cameras into Dansungsa Theater to find my seat. When the film began to roll, the mark left by the censor was clear: a couple scenes were screened without sound, leaving an eerie silence in the theater; the naughty bits had all been blurred; and other scenes had been completely removed, including a particularly lewd conversation about sex between two high school girls and a scene involving coprophilia (look it up in the dictionary). In all, five minutes of footage had been removed from the 113-minute film.

The film itself left many disappointed. Jang has established such a high standard in his works of the past decade that this rather simple tale of a sado-masochistic affair left some of his fans perplexed. Some of Jang's old themes are revisited in this work, namely the complex and at times savage power relations between men and women (cf. the husband and wife in The Lovers of Woomook-baemi, or the writer and his lover in To You, From Me), but on the whole it seemed to devote more energy to pushing buttons, setting up scenes that were certain to shock and infuriate conservative viewers.

The film itself left many disappointed. Jang has established such a high standard in his works of the past decade that this rather simple tale of a sado-masochistic affair left some of his fans perplexed. Some of Jang's old themes are revisited in this work, namely the complex and at times savage power relations between men and women (cf. the husband and wife in The Lovers of Woomook-baemi, or the writer and his lover in To You, From Me), but on the whole it seemed to devote more energy to pushing buttons, setting up scenes that were certain to shock and infuriate conservative viewers.

Much can be read into the film's title. Jang originally intended to use the title of the novel on which the film is based, Lie to Me, which places us inside the narrative, but later he shortened it to just Lies, which can more easily be directed at society in general. Jang has long ridiculed the hypocrisy of Korean society, whose outwardly conservative sexual mores mask a thriving sex industry and widespread exploitation of minors. This double standard has ironically has been reflected in the film's reception. The sex we see in Lies does not feel in any way enticing; the protagonists are left seeming pathetic by the end of the film, and few viewers are likely to go scavenging for sticks after leaving the theater. Nonetheless some groups have labeled even the edited version as dangerous pornography, while turning a blind eye to the far more subversive pornographic videos and CD-roms that are available in department stores, street corners and video shops across the nation.

Jang has had enough experience with censorship and controversy that he must have known exactly the reception his film would receive. In many ways I consider the lawsuits, the rejections by the ratings board, and the protests by citizens groups as much a part of this work as the mise-en-scene and cinematography, for they were clearly planned and anticipated by the director. Jang's experimentation with documentary form in recent years has blurred the distinction between the space inside the film and the world outside; in many ways Lies is just the next step, in which the leaders of various citizens groups and government boards have become unwitting protagonists in the latest Jang Sun-woo film. (Darcy Paquet)

It made perfect sense that Im Kwon-taek would choose to direct this story. With over 90 films to his credit, Im has become somewhat of a father figure in the film industry, revered particularly for the manner in which he celebrates the arts and traditions of old Korea. With his 1993 film Sopyonje he created a feature that, for some, represents the very essence of Korean tradition. Therefore it seemed only fitting that his latest effort would be based on Korea's most famous and best-loved folk tale, Chunhyang.

People often compare this folk tale to Romeo and Juliet, both for its thematic content (teenage lovers secretly married, but separated by class) and for its stature within Korean culture. It has been filmed over a dozen times, notably as Korea's first sound film and then later as a mid-1950's box-office smash that revived the film industry after the war. The character of Chunhyang has become a national icon, admired as much for her beauty and virtue as for her resistance against corrupt authority.

People often compare this folk tale to Romeo and Juliet, both for its thematic content (teenage lovers secretly married, but separated by class) and for its stature within Korean culture. It has been filmed over a dozen times, notably as Korea's first sound film and then later as a mid-1950's box-office smash that revived the film industry after the war. The character of Chunhyang has become a national icon, admired as much for her beauty and virtue as for her resistance against corrupt authority.

This particular adaptation, however, is not simply a retelling of the story; it is built around a pansori narration of the tale. Viewers who have seen Sopyonje will be familiar with the vocal art of pansori, a style of narrative song developed in Korea's countryside. Whereas in Sopyonje viewers were introduced to the beauty of the singing, in Chunhyang the pansori is far more moving, because we follow the story's narration together with the intense swells of the music. This is perhaps the most amazing aspect of this film, that it gives us such access to a little-known but remarkable form of art. The film is structured as a 'story within a concert' where we move between shots of the performer and the story he narrates; and unlike many narratives of this kind, the 'story' and its 'frame' interact to create something greater than the sum of its parts.

This movie features two teenage actors making their debuts: Cho Seung-woo as the earnest but somewhat inconsiderate Mong-ryong, and Lee Hyo-jeong playing Chunhyang, the embodiment of virtue, intelligence, and stubborn will. The screen time they share together is delightful, from Mong-ryong's painting on Chunhyang's dress to their adolescent sexual romping. Another breathtaking aspect of the film are its visuals, shot by veteran cinematographer Jung Il-sung, who has worked closely together with the director in the past.

Although I personally have not been impressed with much of Im's recent work, Chunhyang is a real find. It is the most accessible film of Im's late career, and one of his best ever. (Darcy Paquet)

Addendum: In May 2000, Chunhyang became the first Korean feature film ever to participate in the Competition Section at the Cannes Film Festival. The film was very well received, with some naming it a darkhorse contender for the Palme d'Or, although it ended up not winning a prize.

When you buy a ticket to a film about WWF-style pro wrestling, you usually don't anticipate subtle characterization or complex themes. The Foul King is billed as a comedy, and it certainly is very funny. Nonetheless, this work is far more ambitious than its garish red and yellow posters would have you believe.

Dong-ho is a shy banker who takes up pro wrestling without telling his father. After the repeated abuse leveled on him by his manic, power-obsessed bank manager, he hopes to find in wrestling both a space free of hierarchy and a means of escaping the manager's headlocks. In the course of his training he practices his moves and struggles to attain the self-confidence to deal with his personal and professional life. Eventually, however, he realizes that he must confront his ringside identity as the masked Foul King.

Dong-ho is a shy banker who takes up pro wrestling without telling his father. After the repeated abuse leveled on him by his manic, power-obsessed bank manager, he hopes to find in wrestling both a space free of hierarchy and a means of escaping the manager's headlocks. In the course of his training he practices his moves and struggles to attain the self-confidence to deal with his personal and professional life. Eventually, however, he realizes that he must confront his ringside identity as the masked Foul King.

Director Kim Jee-woon scored a hit in 1998 with his debut feature The Quiet Family, particularly among European audiences. With The Foul King, however, he takes a big step forward, topping his previous feature and firmly establishing himself as a director worth following. Kim wrote the screenplay to this film, and his background in theater comes across in the fine ensemble acting provided by his talented cast, including Chang Jin-young, Park Sang-myun, and notably Song Kang-ho.

Amidst the excitement over this movie, Song Kang-ho has been transformed into a major star. Although well-known for his supporting roles in past films such as No. 3, The Quiet Family, and Shiri, with The Foul King he has found his first opportunity to play a leading role. His skill at expressing both the humor and pathos of his character will ensure that it will not be his last. Aside from acting so well, he also performed most of the flips, drops, and body slams without the aid of a stunt double.

The Foul King has become a sensation in Korea, drawing high critical praise and mobs of enthusiastic viewers. Fans from abroad are likely to become just as excited, when and if they get the opportunity to see it. (Darcy Paquet)

A low-ranking university lecturer (Lee Sung-jae), strained by the pressures of money and his wife's pregnancy, snaps one night at the incessant barking of a neighbor's puppy. After seizing the dog and exacting a cruel revenge, he nonetheless fails to secure the peace and quiet he so desires. Meanwhile, an employee at the apartment office (Bae Doo-na) receives a notice from a young girl about her missing dog...

Barking Dogs Never Bite is hard to characterize: part comedy and part cruel social satire, the film is spiced with scenes and characters which seem unique to the cinema of Korea, or perhaps any country. The film neither looks nor feels like an art film, and yet on closer viewing, the aesthetic it creates is both complex and extremely well-executed.

Barking Dogs Never Bite is hard to characterize: part comedy and part cruel social satire, the film is spiced with scenes and characters which seem unique to the cinema of Korea, or perhaps any country. The film neither looks nor feels like an art film, and yet on closer viewing, the aesthetic it creates is both complex and extremely well-executed.

Part of what makes this film stand out is its characterization. The women characters, for one, contrast sharply with the naive, pretty image that dominates Korean film. Our male lead arouses both sympathy and horror in turn, leaving the viewer unsure of whether to identify with him. Characters like the janitor, with his penchant for Korean dog soup, also leave an unforgettable impression.

My favorite part of this film, though, are the small details scattered throughout: an erratic jazz soundtrack; the predominance of the color yellow; rolling pears; abrupt cuts to airplanes or imaginary cheering crowds; a dispute resolved by a roll of toilet paper; and the hauntingly-narrated tale of "Boiler Kim."

The strength of this, Bong Joon Ho's debut feature, was foreshadowed in 1995 by his amazing short film Incoherence, in which a series of professors are caught in shameful acts unbecoming of their status. Incidentally, here too we see a searing indictment of academia, where rampant drinking parties predominate, and bribery remains the only path to a promotion.

Every time I watch this movie I'm impressed more and more. With so many films made all over the world, it's become rare to find a work that feels like it's writing its own rules. Nowhere to Hide (1999) was one such film, with its wild visuals and stripped narrative. In a much more subtle way, Barking Dogs Never Bite may stake a similar claim. (Darcy Paquet)

Interview follows a film crew while they sort through interviews to make a movie, which may or may not be a documentary, about destined love. In the process, the director within this film, Eun-suk (Lee Jung-jae) seems to be destined to fall in love with one of the interviewees, Young-hee (Shim Eun-ha). We learn through a purposely disjointed narrative that this may not have been when Eun-suk met Young-hee for the first time. Added to this temporal disorientation is further doubt in the events unfolding since Young-hee is as unreliable in her interview as Eun-suk is silent about his past.

I must say that I can be turned off by films about film-making. (I'm sure there may be a film theory term for this, but I don't know what it is.) Yet here I can see some of the value in such meta-films. The repetition that any film crew must suffer through in take after take and that directors and film editors must endure in re-viewing scene after scene is used nicely as we see scenes and dialogue repeated from different angles and different chronological moments. Since Interview is also dealing with memory and how love can color that, this method supports the themes. However, the inclusion of a real life actress playing herself, Kwon Min-jung (Inspector Choi in Two Cops 3), can be unnecessarily distracting since having outed a less prominent actress within the film text, it results in a certain dissonance when seeing a more marquee name such as Shim play the friend of Kwon rather than the star actress that Shim herself is. You'd think, of all the people to be noticed at the cafe where Kwon is approached, it'd be Shim. However, if you are able to suspend the obligatory disbelief, for the most part, Lee Jung-jae puts together a nice subdued performance and Shim's wandering lost soul is believable. (Although her dancing is not.)

I must say that I can be turned off by films about film-making. (I'm sure there may be a film theory term for this, but I don't know what it is.) Yet here I can see some of the value in such meta-films. The repetition that any film crew must suffer through in take after take and that directors and film editors must endure in re-viewing scene after scene is used nicely as we see scenes and dialogue repeated from different angles and different chronological moments. Since Interview is also dealing with memory and how love can color that, this method supports the themes. However, the inclusion of a real life actress playing herself, Kwon Min-jung (Inspector Choi in Two Cops 3), can be unnecessarily distracting since having outed a less prominent actress within the film text, it results in a certain dissonance when seeing a more marquee name such as Shim play the friend of Kwon rather than the star actress that Shim herself is. You'd think, of all the people to be noticed at the cafe where Kwon is approached, it'd be Shim. However, if you are able to suspend the obligatory disbelief, for the most part, Lee Jung-jae puts together a nice subdued performance and Shim's wandering lost soul is believable. (Although her dancing is not.)

Regardless of what one thinks of this film, it will have its place forever in the Korean canon since it was the first, and so far the only, Korean film to follow the Dogma 95 manifesto of aesthetic and production rules presented by Danish filmmakers Lars von Trier and Thomas Vinterberg. And regardless of what you think about Dogma 95's requirements, such as using only hand-held cameras, natural sounds, and props found on location, whether you take a cynical view that this is simply an elitist marketing tool or a hyperbolic view that this is the greatest thing to happen to cinema since sound, Dogma 95 does pose a compelling challenge to any filmmaker who chooses to abide by its tenets.

It has since been revealed to us that many of the Dogma 95 certified films were not following the manifesto 100%. And it appears that director Byun Hyuk (aka Daniel H. Byun) was similarly unable to follow it completely. Byun appears to violate The Vow of Chastity tenet #2, "The sound must never be produced apart from the images or vice versa," in that the soundtrack consists of quite a few songs that are non-diegetic. (That is, outside of the scene taking place, one of the film theory terms I do know, yet I still don't know how to pronounce the term.) And tenet #7 says that "Temporal and geographical alienation are forbidden." So Interview's scrambled time frame appears to disqualify it as well. Still, interesting Dogma 95 moments arise within Interview since this film is about filmmaking. The special lighting which Young-hee holds during one scene to brighten the presence of a couple being interviewed meets the requirement forbidding special lighting (#4) since it is the lighting of the filmmaking process being filmed, making it not so special after all. And concerning the tenet requiring that the props be found on location (#1), this film crew being filmed take advantage of what would be available to them at the office of none other than the producers of this film, Cine 2000, where the characters all work.

Whereas the dialogue appears forced and pretentious at times, (when Eun-suk writes "Are you searching for the truth?" on a Polaroid, I just about cringed), it is the meta-dialogue of the film within a film that salvages Interview for me. The Dogma 95 tenets were a worthy challenge to take on. And although Byun is nowhere close to adding a regal "von" to his name, I get enough out of the film to feel as if I didn't waste my time while relaxing in the unnatural natural light of the cathode ray tube emanating from my TV, hearing the natural sounds of my landlord's kids running around upstairs, all while propped up on the futon and chair cum ottoman props on location at my apartment. (Adam Hartzell)

Few films produced in Korea have generated such a polarized response as The Isle. Most domestic critics abhorred the film, except for a few who gave it four stars. It bombed at the box office, despite an expensive marketing campaign. In the international community it has been met with revulsion, cheers, and an invitation to the Venice Film Festival. The film is certainly a mixed bag -- as for myself, I find it somewhat of an embarrassment.

The movie takes place in a rural fishing area, where a groundskeeper tends after a set of floating cottages, selling her body to the visiting fishermen. Indeed, the setting is one of the most memorable aspects of the film: misty and remote, as well as being the perfect male fantasy. Into this environment comes an ex-cop, on the run from the law after killing his lover. The groundskeeper, who speaks not a word throughout the film (although she does make telephone calls offscreen), becomes fascinated with this man, and the two embark on an intense and hurtful relationship.

The movie takes place in a rural fishing area, where a groundskeeper tends after a set of floating cottages, selling her body to the visiting fishermen. Indeed, the setting is one of the most memorable aspects of the film: misty and remote, as well as being the perfect male fantasy. Into this environment comes an ex-cop, on the run from the law after killing his lover. The groundskeeper, who speaks not a word throughout the film (although she does make telephone calls offscreen), becomes fascinated with this man, and the two embark on an intense and hurtful relationship.

The Isle is nothing if not sensational. From early bits which make the audience squirm, the film gradually climaxes in some horrifying scenes of self-mutilation, which are nonetheless played for laughs by the director. The film is shocking, and it clearly anticipates moral outrage.

Yet on dramatic terms the movie falls apart. The characters' actions seem driven not by any internal motivation, but rather the director's efforts to drive his story forward. The film strives to achieve some sort of dramatic symmetry, but its efforts are so obvious that at times it feels like a parody of itself. Ultimately the film is dishonest with its viewers, and so it is hard to take it seriously.

The film is not without some strengths. Director Kim Ki-duk has a rare talent for color and composition; in fact, before coming to film he studied painting in Paris. All of his works feature striking visuals, which makes one wonder what he might be able to accomplish with a strong screenplay. Also of note is the strong performance by actress Suh Jung, who built her career starring in a series of experimental independent films.

Ultimately, however, the film leaves the viewer with a sick stomach -- for its violence as well as its missed potential. No doubt The Isle will provide the people at Venice with a bit of controversy; it's just a shame they couldn't have picked one of the better films that this industry has to offer. (Darcy Paquet)

The Virgin Stripped Bare by her Bachelors

The Virgin Stripped Bare by her Bachelors

Hong Sangsoo has built himself a stong following abroad with his sober art films The Day a Pig Fell Into the Well and The Power of Kangwon Province. His latest release, titled The Virgin Stripped Bare by her Bachelors, will only add to his reputation as being the strongest and most cerebral of contemporary Korean filmmakers.

Virgin appears at first sight to be the simplest of his three works. Soojung (24), a writer and assistant at a small video company, is pursued in turn by her boss, Young Soo (37), and his former classmate, the wealthy Jae Hoon (35). Jae Hoon pressures her to have sex with him, but she continues to put him off, as his pleading grows ever more insistent. Despite this simple storyline, however, the film's plot evolves into much more of a tangle, with the conflicting memories of Soojung and Jae Hoon leaving the viewer with little sure ground to stand on. The film stars Lee Eun-ju, Moon Sung-keun, and Jung Bo-seok, who all excel in capturing the isolation felt by their characters.

Virgin appears at first sight to be the simplest of his three works. Soojung (24), a writer and assistant at a small video company, is pursued in turn by her boss, Young Soo (37), and his former classmate, the wealthy Jae Hoon (35). Jae Hoon pressures her to have sex with him, but she continues to put him off, as his pleading grows ever more insistent. Despite this simple storyline, however, the film's plot evolves into much more of a tangle, with the conflicting memories of Soojung and Jae Hoon leaving the viewer with little sure ground to stand on. The film stars Lee Eun-ju, Moon Sung-keun, and Jung Bo-seok, who all excel in capturing the isolation felt by their characters.

For the first time, Hong has chosen to shoot a film in black and white. In the film's press kit, he explains why: "Color gives viewers more information than they need. A screen simplified in black and white, on the other hand, lets the audience concentrate on the characters and discern emotional changes without being disturbed by peripheral objects and environment." Indeed, Virgin feels much different from his earlier works, despite the similarities in theme and characterization. The film contains some beautiful images, which seem to take on an archival quality in black and white.

As in his previous works, Hong has picked a curious title for this film. The Korean title, Oh! Soojung, works both as a pun on a common Korean name and as a sexually-tinged reference ('Soojung' means 'fertilization' in Korean). The English title, in turn, is taken from a 1930's-era artwork by Marcel Duchamp titled "The Bride Stripped Bare by her Bachelors, Even." A green box containing one color plate and 93 reproductions of notes, photographs, and drawings of an unfinished painting, Duchamp's ardor for replication provides an interesting counterpoint to the multiple layers of Hong's film. (Click here for a detailed description of Duchamp's work)

I don't wish to give too much of this film away; it's more interesting when you discover it for yourself. It will likely travel the globe on the international film circuit, having already screened in Un Certain Regard at Cannes, and Hong's fans would be well-advised not to miss it. (Darcy Paquet)

Most film critics save their worst insults for melodrama. They view its excess as unnecessary and its appeal to tears insulting, in much the same way that horror films were derided in the past for appealing to base emotions. A recent New York Times reviewer cast doubt on whether it was even possible to have a melodrama that produced both tears and any meaningful reflection.

Ditto is unlikely to change such critics' attitudes, nonetheless for more sympathetic viewers this film may prove to be a treat. It focuses on a female university student from 1979 who begins talking via HAM radio with another student from her school. They hope to meet, but through a series of misunderstandings she begins to realize that the other student lives in the year 2000. This bit of the supernatural (which is portrayed quite matter-of-factly) serves as the foundation for an exchange between these two, who are separated by two decades in which their culture has been transformed.

Ditto is unlikely to change such critics' attitudes, nonetheless for more sympathetic viewers this film may prove to be a treat. It focuses on a female university student from 1979 who begins talking via HAM radio with another student from her school. They hope to meet, but through a series of misunderstandings she begins to realize that the other student lives in the year 2000. This bit of the supernatural (which is portrayed quite matter-of-factly) serves as the foundation for an exchange between these two, who are separated by two decades in which their culture has been transformed.

This film's excesses are not hard to spot. Cuteness abounds, and music is spooned on like syrup, from Bach cello suites to Korean hit songs of the 1970's. Nonetheless it draws its power from a rather simple juxtaposition, and the film's best moments are formed by the questions the two characters have for each other.

Most people expected Ditto to do very little at the box office. It opened on a small number of screens, but its persistent appeal with viewers extended its release and turned it into a financial success. Much of this was attributed to the film's stars, Yoo Ji-tae and Kim Hanul, who both have large numbers of adoring fans (particularly Yoo Ji-tae, whose rising popularity has become a recent phenomenon). First-time director Kim Jung-kwon deserves his share of the credit, as well as the film's screenwriter, Jang Jin, who apart from his own films (The Spy, The Happenings) has also worked on such interesting screenplays as A Hot Roof (1995).

Large numbers of Korean films seem to contain borders that can't be crossed. These borders may be drawn by time, crossed loyalties, strict social codes, or distance. No doubt this feeling resonates for a nation that was divided in two by foreign powers, separating countless families and loved ones. These days as a thaw opens up on the Korean peninsula, visitors to the North describe their experience as resembling a trip back in time to the Korea of the 1950's or 60's. Ditto is constructed around a supernatural event, but if Korea should ever reunify, perhaps the situations portrayed in this film will not feel as far-fetched. (Darcy Paquet)

Kuho is driving home with friends when their car hits Mi-jo, a 15-year old girl standing in the middle of the road. Miraculously, the girl survives, but she is unable to speak and seems to have no recollection of her past. Kuho takes her into his home and soon becomes fascinated with her sad eyes and heavy silence.

When he loses her one day at an amusement park, he hears her calling him inside his head, and a series of visions flash across his mind, leading him to her. He discovers that Mi-jo is able to communicate with him by thoughts and images. Kuho and the young girl become more and more attached, but as troubling vestiges of her past begin to surface, they discover that the girl's psychic capabilities are far more intense than either of them had realized.

When he loses her one day at an amusement park, he hears her calling him inside his head, and a series of visions flash across his mind, leading him to her. He discovers that Mi-jo is able to communicate with him by thoughts and images. Kuho and the young girl become more and more attached, but as troubling vestiges of her past begin to surface, they discover that the girl's psychic capabilities are far more intense than either of them had realized.

After the huge success of his film Whispering Corridors, Park Ki-Hyung turned to an independent production company and a much quieter script for his second feature. Despite its supernatural motifs, Secret Tears is slow-paced and introspective, more centered around a sense of modern-day isolation than on the powers of its young heroine. The relationships portrayed in the film - those of friends or of lovers - are punctuated by long silences that undermine their supposed intimacy. The only bond that achieves any closeness is the one between our two main characters. Their ability to talk without speaking seems to place them into a parallel world.

Also raised by the film (though not fully explored) are issues of sexuality, with dark events from Mi-jo's past placed alongside the Lolita-esque, but nonphysical, relationship between the 33-year old Kumo and the young girl.

With its stylish visuals and personally-oriented themes, Secret Tears serves as a representative example of a new aesthetic developing among young Korean filmmakers. Unfortunately, however, the film itself seems to weaken in the second half, relying on its mood rather than developing the narrative any further. While its visuals are unforgettable, the movie ultimately fails to live up to the promise of its director. (Darcy Paquet)

The Korean blockbuster is a new phenomenon. Shiri was probably the first, and I would argue that after last year's release of Tell Me Something, Bichunmoo is the third. Blockbusters operate under different rules: the conventions of genre usually shape their plots, with big-budget special effects and star power a central part of their appeal. It has been interesting to see how domestic audiences have responded to this new phenomenon; despite high box-office returns, the films have usually provoked a strong backlash from viewers (with the exception of Shiri).

Bichunmoo is modeled after Hong Kong swordplay films. All shooting was done on location in China, and Hong Kong star Ma Yuk-shing worked as action director for the film. The story is based on a popular serial comic by Kim Hye-rin that ran in the late 1980s. Set in China under the Yuan Dynasty, the film centers around Jinha, an apprentice in the art of Bichunmoo swordplay, and Sullie, the daughter of a Mongol general. The two lovers become separated after the death of Sullie's mother, and a string of rivals and misunderstandings cause them to grow further apart.

Bichunmoo is modeled after Hong Kong swordplay films. All shooting was done on location in China, and Hong Kong star Ma Yuk-shing worked as action director for the film. The story is based on a popular serial comic by Kim Hye-rin that ran in the late 1980s. Set in China under the Yuan Dynasty, the film centers around Jinha, an apprentice in the art of Bichunmoo swordplay, and Sullie, the daughter of a Mongol general. The two lovers become separated after the death of Sullie's mother, and a string of rivals and misunderstandings cause them to grow further apart.

The film was a big hit with audiences, especially teenagers. By the end of the summer it had outperformed every Hollywood release except Mission: Impossible 2 and Gladiator. Particularly impressive were the action sequences and special effects, the likes of which have never really been seen before in Korean cinema. Nonetheless there were dissenting voices, as anti-Bichunmoo websites began sprouting up across the internet.

Part of the disappointment came from fans of the original comic, an epic work that spans six volumes. Kim Hye-rin's story and the complexities of her characters were highly simplified in the film version, provoking the kind of ire felt in the U.S. by Anne Rice fans upon the release of Interview With the Vampire.

However, viewers' disappointment may also be linked (without them realizing it) to the distributor's decision to eliminate some scenes from the domestic release. Korean filmmakers are under intense pressure to keep films short, so that theaters can fit in six screenings per day and maximize returns. Bichunmoo is comparatively long at just over two hours, and so four short scenes were removed. Three of these scenes help to characterize our heroes and explain the background of a recurrent painting, but the fourth deleted scene is crucial; it (1) introduces two major characters, (2) informs us that Jinha has adopted a new name, (3) informs us that Jinha has sided with the anti-Mongol forces, (4) outlines the group's strategy of attack, and (5) explains the origin of the Ten Swordsmen who accompany Jinha. Without this background information, Korean viewers were noticeably confused and annoyed with the unfolding of the plot. Fortunately it appears that these scenes will be retained in the international version of the film.

Director Kim Young-jun was given a well-known group of actors for this film, but in some ways the casting may be one of the film's weaker elements. Actress Kim Hee-sun looks stunning in her period dresses, but her character lacks the fire that could have made this a standout film. Jung Jin-young (The Ring Virus) also seems miscast as Jinha's rival, inspiring neither dread nor admiration. Lead actor Shin Hyun-june, however, seems born for the part he plays, and although his power grows fearsome by the end of the film, he maintains the boyish vulnerability that defines his character.

As entertainment Bichunmoo succeeds pretty well. Its lush setting and explosive visuals provide a kind of treat that is rare in Korean film. Many of the criticisms leveled at this work have come from expectations that it would be something else; taken as what it is, Bichunmoo is worth seeing. (Darcy Paquet)

Die Bad ranks as one of the most astonishing debut films in recent memory. It is expertly woven together from four shorts, separately filmed over three years. "Rumble," set entirely in a billiard room, introduces protagonists Seok-whan (played by the director, Ryu Seung-wan) and Seong-bin (Park Seong-bin). In the midst of a nasty run-in with kids from an art school, Seong-bin accidentally commits a murder. In "Nightmare," we meet him after a seven-year stint in prison. Haunted by the ghostly vision of the art student he killed, Seong-bin finds himself drifting into the underworld, when he saves the life of a local boss, Kim Tae-hoon. "Modern Man," an award winner at Seoul Independent Short Film Festival, cross-cuts between mock interviews of Tae-hoon and Seok-whan, now a cop, who responds to the questions with a mixture of pragmatic cynicism and deadpan humor, and a harrowing, extended fistfight between them. In the final episode, "Die Bad," a mini-film noir shot in black and white, Seok-whan and Seong-bin's destinies intertwine for the final time, with the life of Seok-whan's kid brother, Sang-whan, hanging in the balance.

Costing somewhere in the vicinity of 65 million won, which would not have paid for a two-second shot of CGI in a blockbuster, Die Bad is not a sleek corporate product. The visuals are grainy and cheap-looking (Part of the movie was filmed with the stock left over from Jang Seon-woo's Bad Movie), performances sometimes stiff, action choreography occasionally rough-and-tumble. There are typical B-movie moments such as a boom mike dropping into the frame. However, these low-budget limitations play to the film's strengths. If anything, they enhance its gritty, authentic atmosphere.

Costing somewhere in the vicinity of 65 million won, which would not have paid for a two-second shot of CGI in a blockbuster, Die Bad is not a sleek corporate product. The visuals are grainy and cheap-looking (Part of the movie was filmed with the stock left over from Jang Seon-woo's Bad Movie), performances sometimes stiff, action choreography occasionally rough-and-tumble. There are typical B-movie moments such as a boom mike dropping into the frame. However, these low-budget limitations play to the film's strengths. If anything, they enhance its gritty, authentic atmosphere.

Die Bad reminds one of the film-noir classics of prewar Hollywood in its economy and directness, but it is also unmistakably contemporary in its rough-hewn but dazzling mise en scene. In the hands of Ryu Seung-wan, who seems to have forgotten any sense of auteuristic self-importance before he ever learned it, genre cliches are transformed into something new or distilled into their pure essence. A domestic spat in which Seong-bin's father (played by the major '80s director Lee Jang-ho) berates and abuses his family, the kind of scene rendered so familiar in countless TV dramas, cuts like a knife here. Tae-hoon, brilliantly portrayed by a veteran bit player Bae Jung-shik, is a thoroughly believable thug, with nary a bone of macho strut in his whip-lean body: tersely ironic in "Modern Man," ferocious but coolly intelligent in "Nightmare." And barrels of insults, threats and silly jokes that Seung-whan (Ryu Seung-beom, the director's real-life brother, in a startling, naturalistic turn) and his mates toss at one another like so many spitballs, sound utterly unaffected, real: they carry the cadences of actual street kids mouthing off, not those of actors reciting lines off a screenplay. Underlying all this, like a bass guitar in a rock' n roll riff, is a primal scream of a theme: crushing indifference of the world (or perhaps heartlessness of God?) toward its underprivileged inhabitants, who have no choice but to end up "dead" or "bad" (the original Korean title translates as "Dead or Bad"), or as in the case of some characters of this ultimately unromantic film, both.

Ryu's style has often been compared to that of Quentin Tarantino, but I do not see much resemblance between Ryu's adroit command of visual language and Tarantino's verbose, neo-Beatnik sensibility. One film that Die Bad does bring to my mind is Mean Streets (1973), Martin Scorsese's similarly raw and devastating take on another group of underprivileged inhabitants of another indifferent world. Could Ryu Seung-wan emerge in the near future as Korea's answer to Scorsese? Perhaps it is unfair to burden him with such a high expectation. It is sufficient at this juncture to note that, with his debut feature, Ryu (and his hardworking and talented collaborators) created a minor masterpiece that leaves one open-mouthed in admiration of its hutzpah and virtuosity. (Kyu Hyun Kim)

One of the more successful films made in the wake of the teen horror boom of 2000 stimulated by the glossy Hollywood products Scream (probably the most overrated American film of the 1990s) and I Know What You Did Last Summer, Nightmare marks the feature film debut of the director Ahn Byeong-ki (Phone) and actress Ha Ji-won (Sex is Zero, Phone).

Ha plays a pretty but shadowy college freshman Eun-joo. She is befriended by a kindly upperclassman, Hye-jin (Kim Gyu-ri, from Whispering Corridors), and joins her coterie of friends, the video freak Se-hun (Jeong Jun), the snooty law school student Jeong-wook (Yu Jun-sang, Tell Me Something), the prima donna Seon-ae (Choi Jeong-yun) and the star baseball player Hyeon-jun (Yu Ji-tae, Attack the Gas Station, One Fine Spring Day, stuck in a thankless dumb-jock role). When Hyeon-jun dumps Seon-ae in favor of the mysteriously alluring Eun-joo, the incensed Seon-ae digs up her competitor's hidden past. It seems that Eun-joo used to be a "jinxed" presence in the village she grew up under the name Gyung-a, ostracized for her alleged supernatural powers. Hye-jin, believing that Eun-joo/Gyung-a was responsible for her father's death, spurns the latter, only to observe her apparent suicide during a rainy night. But is she truly dead?

Ha plays a pretty but shadowy college freshman Eun-joo. She is befriended by a kindly upperclassman, Hye-jin (Kim Gyu-ri, from Whispering Corridors), and joins her coterie of friends, the video freak Se-hun (Jeong Jun), the snooty law school student Jeong-wook (Yu Jun-sang, Tell Me Something), the prima donna Seon-ae (Choi Jeong-yun) and the star baseball player Hyeon-jun (Yu Ji-tae, Attack the Gas Station, One Fine Spring Day, stuck in a thankless dumb-jock role). When Hyeon-jun dumps Seon-ae in favor of the mysteriously alluring Eun-joo, the incensed Seon-ae digs up her competitor's hidden past. It seems that Eun-joo used to be a "jinxed" presence in the village she grew up under the name Gyung-a, ostracized for her alleged supernatural powers. Hye-jin, believing that Eun-joo/Gyung-a was responsible for her father's death, spurns the latter, only to observe her apparent suicide during a rainy night. But is she truly dead?

Nightmare is an earnest effort by a young director clearly in love with the horror film genre. Compared to the wink-wink "postmodern" posture of Scream and its clones, Ahn's attitude is almost classicist: he is single-minded in his pursuit of jacking up the scare quotient, using every trick he has at his disposal. Ahn unabashedly embraces the unrefined cliches we tend to associate with the archaic superstitions (a black cat run over by a car, etc.) and tacky TV shows that used to scare us as children. There are a few genuinely impressive set pieces, such as the telephone booth attack, that creatively adapts the imagery from superior horror films such as Videodrome and Inferno.

In the end, though, Nightmare fails to rise above the level of a serviceable entertainment. There is altogether too much blood, too many instances of sudden bursts of music in the soundtrack, too many shots of slow motion, too many goofs that break the spell of verisimilitude (the most glaring boo-boo being that "accidentally captured" video footage serving as the climactic revelation: I guess it was Gyung-a's supernatural power that made the camcoder focus on her eyes on its own?) and too much hamming by principal actors. Regrettably, unintentional hilarity begins to creep in by the time the film reaches its overcooked climax.

The film is mostly recommended to two groups: committed fans of the horror genre, (like myself) and fans of Ha Ji-won. Ha is charming and sympathetic as a shy and awkward freshman courted by her male classmates, and manages to be striking even when attacking Kim Gyu-ri with a pencil, wrapped in a dorky black dress straight out of an old shojo manga.

Note: The Korean title of the movie, Gawi, refers to a dream demon or an incubus. Its method of torment is to press down upon or strangle a sleeping person. Hence the expression "gawi e nullida," "be pushed down by gawi," translated into English as "have a nightmare." This gawi does not mean scissors here ("incubus" and "scissors" are homonyms in Korean), despite what you may read in other websites/magazines. (Kyu Hyun Kim)

For the second year in a row, the Korean film industry has struck gold with a movie about North Korea. Many expected Joint Security Area (or JSA) to do well at the box office, given the current level of interest in North Korean affairs, but it has done much more than that, spawning headlines and breaking box-office records with ease. The film drew close to half a million viewers in Seoul alone its first week. On the following Saturday it set a one-day box office record, drawing 104,000 viewers in the capital. It broke the one million admissions mark in only 15 days -- last year it took Shiri 21 days to reach the same mark. By early 2001 it had become the best-selling film in Korean history (though it was eclipsed by Friend a few months later).

Park Chan-wook's film opens with a shooting in the truce village of Panmunjom which leaves two North Korean soldiers dead and one South Korean soldier wounded. With each country giving conflicting reports on what happened, the Neutral Nations Supervisory Commission (NNSC) is asked to send in a Swiss military officer to conduct an investigation. After her arrival, however, she finds that no one is willing to talk to her, and the soldiers involved all seem to be hiding some secret...

Park Chan-wook's film opens with a shooting in the truce village of Panmunjom which leaves two North Korean soldiers dead and one South Korean soldier wounded. With each country giving conflicting reports on what happened, the Neutral Nations Supervisory Commission (NNSC) is asked to send in a Swiss military officer to conduct an investigation. After her arrival, however, she finds that no one is willing to talk to her, and the soldiers involved all seem to be hiding some secret...

JSA is described as a mystery/ human drama, and its structure is clearly divided into two parts: the investigation by Korean-Swiss Major Sophie Jean, and an extended flashback to the incident between the soldiers. I think most would agree that the film's biggest strength is the flashback, with actors Song Kang-ho and Lee Byung-heon excelling in their roles. This part of the film also features some breathtaking cinematography for the scenes that take place along the Demilitarized Zone.

The mystery element contains less tension, particularly if the viewer knows too much about the plot beforehand. Attention is focused not so much on what happened, but why. This part also contains a large number of scenes in English, which may have to be redubbed if the film opens in English-speaking territories. Nonetheless it has been noted by critics and audience members alike for its rare casting of a female actor (Lee Young-ae) in a non-romantic part.

The producers of the film spared no expense in recreating the setting around Panmunjom. Since shooting at the actual site would obviously not be permitted, Myung Film built a 90% replica of the village of Panmunjom at a cost of some $800,000. The site can be visited to this day at the Seoul Cinema Complex. JSA is also notable for being the first Korean film ever to be shot on Super 35mm film, a special format used in some Hollywood blockbusters that allows for a wide screen (1:2.35) with very clear definition.

The film has won more or less unanimous praise from every sector of Korean society, with one exception: the army. Many in the military have derided the film as pure fantasy, based on an event which could never happen in real life (probably true). In a bizarre incident on September 26, twenty older members of the JSA Veterans' Association stormed into the office of Myung Film, breaking windows and physically threatening the employees of the company. They demanded that the production company issue a public apology to the army and insert notices at the beginning and end of the movie stating that it is a work of fiction. After four hours, the employees of Myung Film acquiesced, and despite vocal objection from the film industry, the group's demands are being met.

Some have compared this film to Shiri because of its superficial resemblance, but it really is a much different work. As relations with North Korea change and the two nations draw closer together, this film perhaps serves best as a record of South Koreans' fears and hopes for reconciliation. (Darcy Paquet)

This time-travel romance was not a popular success in 2000, selling less than a quarter million tickets in Seoul (upstaged by not only the similar-themed Ditto, but also the not-exactly-audience-friendly Lies), but since then it has developed a loyal fan base a la Somewhere in Time and attained the status of a minor classic. Seen from the vantage point of 2004, I am surprised at how affecting and heartfelt it remains in the end, although a good deal of the movie is hopelessly cliched or rather dull.

Seong-hyun, an aspiring architect, moves into a beach-house designed by his estranged father, which he names Il Mare ("the sea" in Italian). One day he receives a letter from Eun-joo, a voice actress, addressed to the person who will move into "Il Mare" after her. Since he is the first and only person to live in the house, Seong-hyun takes it for a joke or a wrong delivery. However, as they keep corresponding with one another, they realize that Eun-joo is actually living in late 1999, two years into Seong-hyun's future. Initially bewildered and amused by the situation, they are gradually attracted to one another, and start thinking about meeting "in real time." However, they are about to discover a lot of things can happen to one's life in two years.

Seong-hyun, an aspiring architect, moves into a beach-house designed by his estranged father, which he names Il Mare ("the sea" in Italian). One day he receives a letter from Eun-joo, a voice actress, addressed to the person who will move into "Il Mare" after her. Since he is the first and only person to live in the house, Seong-hyun takes it for a joke or a wrong delivery. However, as they keep corresponding with one another, they realize that Eun-joo is actually living in late 1999, two years into Seong-hyun's future. Initially bewildered and amused by the situation, they are gradually attracted to one another, and start thinking about meeting "in real time." However, they are about to discover a lot of things can happen to one's life in two years.

Il Mare will surely test the patience of sci-fi writers wracking their brains to come up with credible solutions to the time paradox. To give where the credit is due, though, I must admit that the screenplay by Yeo Ji-na manages to keep the drama streamlined with some creative touches. It was an inspired idea to reduce "the time gap" to only two years, between 1997 and 1999, and to deliberately limit the contact between the romantic leads to the archaic means of exchanging letters and other artifacts, allowing the characters (and the viewers) to enjoy the tantalizing prospect of a long-distance relationship without the messy emotional spillovers of phone conversations. (Of course, some viewers will inevitably wonder why it takes so long for Eun-joo to start looking for the future incarnation of Seong-hyun)

Lee Jeong-jae is effective as a rather bland male lead: this type of sotto voce, outwardly withdrawn character is far better suited to his persona than a face-contorting harlequin in Last Present or a dour, blank underclass rebel in Les Insurges. On the other hand, those who are only familiar with the post-2001 Jeon Ji-hyeon might be surprised, even baffled, by her portrayal of Eun-joo. Even though she was only nineteen at the time of filming, Jeon looks more mature here than in any of her subsequent films (despite some baby fat on her china-doll face). As someone who finds the way Jeon's pupils completely roll off into the sides of her eyes a tad scary, and cannot help but think of Meowth on speed when watching her "techno-dance" routines and advertisements, her Eun-joo is, along with The Uninvited, a pleasant reminder of her ability to play quieter, human-scaled characters.

But the true appeal of Il Mare to many viewers no doubt lies in its superb production design supervised by Kim Ki-cheol and the staff as well as Alex Hong's exquisite cinematography (whose penchant for capturing the sea in its various permutations of color, from invitingly coral-blue and azure to mysteriously gray, is on breathtaking display here). I can't say that director Lee Hyun-seung shows the same degree of mastery over the story and the characters as his command of the arresting visuals, but what he has presented here is sufficiently rewarding for me to anticipate his next project with some eagerness.

The bottom line about Il Mare is that it is two hours of non-pushy entertainment that is also aesthetically pleasing, like an Impressionist painting of an unremarkable beachfront that nonetheless grasps a rare moment of nature's beauty at its most relaxed. After the semi-colonization of Korean cinema by spasmodic, attention-deficit "romantic comedies," exemplified by Jeon's own My Sassy Girl and its countless spawns, what initially might have appeared in 2000 like vapid affectation now seems to be an embodiment of a lost cinematic virtue: restraint.

Addendum: I must make a special note of the fact that Il Mare's English subtitles in the Spectrum DVD versions, including its "special edition" re-release, and presumably in the 35mm prints, are some of the very worst ever garnished South Korean films. Nearly every other sentence, if not making hash out of Korean dialogues, is then flat-out incomprehensible. It is disheartening to realize that many non-Korean-speaking fans of this film might have become its fans without understanding what in the name of Gabriel's Trumpet the characters are talking about. I think they deserve better. The English subtitles should be re-done for any future media presentation of Il Mare. (Kyu Hyun Kim)

The year following Shiri, another much less successful ichthyologically-titled film appeared, Kim Hyung-tae's Pisces. Although not a North Korea/South Korea action film, there is a divide within Pisces, but one of crossing genres. And this genre-crossing comes as quite a surprise, particularly due to genre conventions that don't allow for the drastic shift we eventually witness.

Ae-ryun (Lee Mi-yeon -- Last Witness, Whispering Corridors) is a new small business owner of a video rental store called "Sad Movie." (I don't know about you, but I just can't call these places "video and DVD rental stores" or, as so many will eventually be, "DVD stores," just as I still call stores that only sell CDs, "record stores.") Ae-ryun is presented to us as parentless, having, by default, become the surrogate parent of her younger brother who also works at her store. As proprietor of this shop, she meets Dong-suk (Choi Woo-jae), a struggling musician -- who makes you want to ask, 'Uhm, where does he get the money to afford his elaborate keyboards, computers, and apartment when he has nothing that resembles an actual job?' -- who also has a fascination for French films. Ae-ryun also apparently has an interest in French films and she and Dong-suk soon discover they have a lot in common, such as an appreciation for the same "Lemon Peel Angel" fish. Unfortunately, compared to other romance dramas, the developing relationship between these two is quite weak.

Ae-ryun (Lee Mi-yeon -- Last Witness, Whispering Corridors) is a new small business owner of a video rental store called "Sad Movie." (I don't know about you, but I just can't call these places "video and DVD rental stores" or, as so many will eventually be, "DVD stores," just as I still call stores that only sell CDs, "record stores.") Ae-ryun is presented to us as parentless, having, by default, become the surrogate parent of her younger brother who also works at her store. As proprietor of this shop, she meets Dong-suk (Choi Woo-jae), a struggling musician -- who makes you want to ask, 'Uhm, where does he get the money to afford his elaborate keyboards, computers, and apartment when he has nothing that resembles an actual job?' -- who also has a fascination for French films. Ae-ryun also apparently has an interest in French films and she and Dong-suk soon discover they have a lot in common, such as an appreciation for the same "Lemon Peel Angel" fish. Unfortunately, compared to other romance dramas, the developing relationship between these two is quite weak.

But when Ae-ryun confesses her feelings to Dong-suk when she knows he already has a girlfriend, the genre shift occurs which shines new light on the awkward development we just witnessed. To state how it shifts and what genre it shifts to would ruin later surprises in the film. But what I can say is that this genre shift represents the tradition of "genrebending" in recent Korean cinema that Darcy has written about here at Koreanfilm.org. Within this genrebending, there are two primary types, those that mix and match throughout the narrative, such as Nowhere To Hide and My Sassy Girl, and those that shift drastically from one to the other, usually in the middle of the film, such as Sex Is Zero. Pisces is of this latter type. Such genrebending is not "wrong," but stepping away from expected genre conventions will often leave viewers feeling ungrounded. When the shift occurred in Pisces, I found myself being very confused and questioning Kim Hyung-tae's direction. However, thinking back upon the film post-shift, I recalled certain items that Kim dropped as breadcrumbs to guide us logically back through the narrative. What previously seemed to be weak development of this relationship now seemed appropriate considering where the characters were headed within the plot. I was wondering why Ae-ryun's only friend was an obnoxious narcissist, and now I know why. Whereas Sex Is Zero's genre shift represents a critique of certain philosophies and politics of the previous genre, thus leaving me, since I disagree with director Yoon Je-gyun's argument, with the impression of a shift to a horror film rather than the family melodrama I believe Yoon intended, Pisces's genre-shift can be seen as a critique of the genre cliches presented before the shift. Pisces ends up explicating from its initial genre what has always lied beneath many romantic tropes.

Still, as much as Pisces fits within a larger trend in contemporary Korean cinema, it is not a quality example of it. Too many poor editing choices results in much of Pisces dragging on for far too long. A whole twenty minutes or more could have been cut from this film. Although the acting isn't horrible, neither does anyone's performance particularly stand out, even during the latter half of the film when the plot should allow -- but doesn't - for more vibrant performances. The film lacks any considerable build up to possible climaxes and scenes falter that require intense emotions to pull the viewer through them. As a result, Pisces is a genre out of water. Purposely out of its element, however commendable such risk-taking is, it fails to entertain within either genre. (Adam Hartzell)

As local production companies churn out more and more high-budget films, Korean blockbusters face serious competition for the first time in their short history. Libera Me opened on November 11 in a highly competitive atmosphere, opposite the much-anticipated The Legend of Gingko and only two weeks after The Siren, another action film centered around firefighters. While at first overshadowed by its bigger rival Gingko, Libera Me has gathered momentum over time, and has drawn deserved praise for its well-crafted action and drama.

The story centers around a mentally-unbalanced arsonist and the firefighters who struggle to stop him. Although thoroughly conventional in its subject matter, the film manages to feel fresh through skilled direction and strong acting from its all-star cast. Special praise goes to leads Choi Min-soo, Yoo Ji-tae, and Cha Seung-won who complement each other well (the group also forms perhaps the best-looking acting trio in recent memory). Among a strong cast of supporting characters, Park Sang-myun (The Foul King) stands out and Kim Kyu-ri (Whispering Corridors) rescues the film from being a thoroughly male-centered affair, even if her character does seem to serve no purpose.

The story centers around a mentally-unbalanced arsonist and the firefighters who struggle to stop him. Although thoroughly conventional in its subject matter, the film manages to feel fresh through skilled direction and strong acting from its all-star cast. Special praise goes to leads Choi Min-soo, Yoo Ji-tae, and Cha Seung-won who complement each other well (the group also forms perhaps the best-looking acting trio in recent memory). Among a strong cast of supporting characters, Park Sang-myun (The Foul King) stands out and Kim Kyu-ri (Whispering Corridors) rescues the film from being a thoroughly male-centered affair, even if her character does seem to serve no purpose.

The makers of Libera Me made full use of their US$4 million budget in bringing their spectacle to the screen. Shot in Pusan with the enthusiastic support of the city and its local fire department, the film deserves exceptional praise for its special effects. Spurning the use of miniatures, the film was shot in real buildings throughout Pusan using a special synthetic oil that allowed the crew to use actual fire. For a key scene involving a gas station, a life-size set was constructed and detonated at a cost of some US$250,000.

Director Yang Yoon-ho boasts one of the stranger resumes in the Korean film community. His debut work Yuri, which centers around a Buddhist monk, won critical praise as well as an invitation to the 1996 Cannes Film Festival. However, his subsequent features -- Mister Condom (1997), Zzang (1998), and White Valentine (1999), all failed to impress critics while doing little at the box-office. White Valentine in particular is bizarrely unique in its framing of a silly melodramatic script with long shots and no camera movement (sort of like a cross between Spring in My Hometown and The Letter). With Libera Me, however, Yang seems more at ease with his craft, and aside from some jarring ellipses he delivers poignant action scenes shot with cinematic flair.

The movie's title, which means 'save me' in Latin, was taken from a movement of French composer Gabriel Faure's Requiem, which also serves as the soundtrack's main theme. The music suits the film well, imparting a tragic air to one of the more intelligently-shot Korean blockbusters in the short history of the genre. (Darcy Paquet)

Between his financially successful 1998 film, The Affair, and his immensely successful Untold Scandal in 2003, E J-yong directed a film that did not perform well financially, Asako in Ruby Shoes. Lee Jung-jae, who was also featured in E's debut, plays E U-in, a Korean civil servant bored and unfulfilled in his job and life. Void of a circle of friends, U-in spends his nights cruising internet porn sites. His voyeurism does not stop with his nighttime activities, however, for he also engages in stalking a woman unavailable to him, a young, punkish woman (Kim Min-heui) whose hair is dyed a fire-y Run Lola Run-ish red. One day U-in receives a spam email that he proceeds to reinforce by clicking on the provided link. He is asked to type in his perfect woman and he proceeds to type in the demographics of Mia, the object of his daytime gaze. From here, the titular character is created from U-in's gaze, Asako in Ruby Shoes.

The women behind the gaze that is Asako is a young Japanese named Aya (Tachibana Misato) who has found her life to be similarly soulless. Having decided on a unique form of suicide, she plans to hold her breath across the International Date Line so as to confuse whether she died today or yesterday, she decides to forgo her future and stop attending her pre-college classes. Getting a job at a health club, she befriends a co-worker, Rie (Awata Urara), a slightly manic-depressive loner who is attracted to Middle Eastern men. After eventually being fired from the health club, Aya decides to pursue a "modeling" gig in order to afford her trip to the International Date Line and to fully pay for the object of her gaze, the Dorothy-esque Ruby Shoes.

The women behind the gaze that is Asako is a young Japanese named Aya (Tachibana Misato) who has found her life to be similarly soulless. Having decided on a unique form of suicide, she plans to hold her breath across the International Date Line so as to confuse whether she died today or yesterday, she decides to forgo her future and stop attending her pre-college classes. Getting a job at a health club, she befriends a co-worker, Rie (Awata Urara), a slightly manic-depressive loner who is attracted to Middle Eastern men. After eventually being fired from the health club, Aya decides to pursue a "modeling" gig in order to afford her trip to the International Date Line and to fully pay for the object of her gaze, the Dorothy-esque Ruby Shoes.

A Korean/Japanese production, E appears to be presenting a play within a play. That is, the global nature of this production, jumping back and forth from Korea and Japan, is represented in each main character feeling out of place in their respective "homes." Where U-in's retreats to the internet represent a need to escape from his place in life, Aya's flight to her death is really a desire to travel outside of the confines of her home life. When U-in attends a banquet to raise funds for his friend's Committee to Establish a New Chinatown in Korea, he says he "feels kinda shitty . . ." realizing he's the only one of Korean ethnicity in the hall. His friend relates. "Feeling strange and out of place? I probably feel the same way in Korea." Whereas Chinese immigrants are presented to question who is truly at home in Korea, and what "home" really means, the Japanese side of the equation features an Iranian character who is eventually displaced. Other characters present similar continuity with the global questions, as does the irony that U-in works as a public servant for a "public" he very much wants to leave.

Lee Jung-jae is perfect casting for this role. Lee possesses the kind of face that allows for the effortless conveyance of innocence and humility. I've only seen Lee in four of his films and have always felt as if I was eating Papa Bear's or Mama Bear's porridge, that is, a little too much and a little too little in his portrayals. However, E U-in is Baby Bear's porridge for Lee. Just right. Tachibana Misato presents a nice subtle range in her role, with a wonderful scene where she must playfully lie when caught hopping the fence into her late grandmother's home. The supporting cast of Kim Min-huei and Awata Urara provide excellent caricatures with the appropriate depth to not appear as if emerging from a vacuum.

Asako in Ruby Shoes has a slow pace, the type of film I prefer, and the camera angles and mise-en-scenes allow for some beautiful images, such as an above view of U-in lying naked and eating watermelon between his legs while submerged in an icy bathtub on a hot day. Although the film is not about the complicated issues surrounding internet porn, (Aya's foray into that world is quite tame and U-in is presented to us as not someone who visits the more extreme sites out there), the ending still poses some problems, appearing too clean and easy. However, although not successful financially, E was quite successful in presenting to us his artistic gifts. Where Asako in Ruby Shoes also succeeds is in providing yet another challenge to views of a homogeneous South Korea by presenting to us the Asian side of modern globalization. (Adam Hartzell)