2016

"The Wailing", "The Handmaiden", "The Age of Shadows", "Dong-ju"

The year 2016 is one filled with anticipation for Korean cinema fans. With an unusually large number of high-profile directors getting ready to release new films, the level of local and international interest is already quite high.

Probably the most talked-about film in the months leading up to its release was The Handmaiden, the new feature from Oldboy director Park Chan-wook. Inspired by Sarah Waters' novel Fingersmith, and set in the colonial era of the 1930s, the film was invited to screen in competition at Cannes -- the first Korean film to receive that honor since 2012. Also invited to Cannes in a high-profile out of competition slot was Na Hong-jin's creepy The Wailing, a film that for several years has been generating buzz among those who have read the screenplay. And not to be overlooked is Kim Jee-woon, whose colonial-era The Age of Shadows starring Song Kang-ho is scheduled for a release in the second half of the year.

As usual the films slated for release in 2016 are quite diverse, but one unmistakable trend is the large number of films being set in the colonial period (1910-1945). Although 2015's Assassination was the first major commercial success for films set during this dark historical era, the trend only seems to be gaining strength. Two lower-budget films from early 2016, Spirits' Homecoming and Dong-ju: The Portrait of a Poet, provoked much discussion and performed much better at the box-office than anyone anticipated. With more films like Ryoo Seung-wan's Battleship Island slated for 2017, it looks like a long-term trend. (Written on April 22)

Reviewed below: Sori: Voice from the Heart (Jan 27) -- No Tomorrow (Mar 3) -- Fourth Place (Apr 13) -- The Wailing (May 11) -- The Handmaiden (Jun 1) -- The World of Us (Jun 16) -- The Truth Beneath (Jun 23) -- Train to Busan (Jul 20) -- Operation Chromite (Jul 27) -- Seoul Station (Aug 17) -- Asura: City of Madness (Sep 28) -- Yourself and Yours (Nov 10) -- Vanishing Time (Nov 16) -- Pandora (Dec 7).

| Korean Films | Nationwide | Release | Revenue | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Train to Busan | 11,565,795 | Jul 20 | 93.2bn |

| 2 | A Violent Prosecutor | 9,707,581 | Feb 3 | 77.3bn |

| 3 | The Age of Shadows | 7,500,420 | Sep 7 | 61.3bn |

| 4 | Master | 7,147,485 | Dec 21 | 58.0bn |

| 5 | Tunnel | 7,120,508 | Aug 10 | 57.5bn |

| 6 | Operation Chromite | 7,049,854 | Jul 27 | 55.1bn |

| 7 | Luck-Key | 6,975,290 | Oct 13 | 56.4bn |

| 8 | The Wailing | 6,879,908 | May 12 | 55.9bn |

| 9 | The Last Princess | 5,599,229 | Aug 3 | 44.4bn |

| 10 | Pandora | 4,583,152 | Dec 7 | 36.1bn |

| All Films | Nationwide | Release | Revenue | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Train to Busan (Korea) | 11,565,795 | Jul 20 | 93.2bn |

| 2 | A Violent Prosecutor (Korea) | 9,707,581 | Feb 3 | 77.3bn |

| 3 | Captain America: Civil War (US) | 8,677,249 | Apr 27 | 72.7bn |

| 4 | The Age of Shadows (Korea) | 7,500,101 | Sep 7 | 61.3bn |

| 5 | Master (Korea) | 7,147,485 | Dec 21 | 58.0bn |

| 6 | Tunnel (Korea) | 7,120,508 | Aug 10 | 57.5bn |

| 7 | Operation Chromite (Korea) | 7,047,854 | Jul 27 | 55.1bn |

| 8 | Luck-Key (Korea) | 6,975,290 | Oct 13 | 56.4bn |

| 9 | The Wailing (Korea) | 6,879,908 | May 12 | 55.9bn |

| 10 | The Last Princess (Korea) | 5,599,229 | Aug 3 | 44.4bn |

* Still on release. Source: Korean Film Council (www.kobis.or.kr).

Seoul population: 10.4 million

Nationwide population: 50.9 million

South Korean film companies have been accused in recent years of rehashing the same old storylines and ideas. Such criticism might be justified, but on rare occasions, something truly unusual does still slip through the cracks. A quick look at the synopsis of Sori: Voice From the Heart confirms this.

S19 (later to be renamed 'Sori') is a US-built spy satellite that as the film opens is orbiting high above the earth. Although officially it's just an ordinary telecommunications satellite, in reality it's no such thing. Equipped with cutting-edge AI and voice recognition technology, it has been secretly tasked with tracking all phone conversations taking place down on earth. But eventually, the self-aware satellite figures out that the conversations it records are being used to target drone strikes in which innocent civilians are among the dead and wounded. Tormented, Sori decides to go AWOL.

Meanwhile, Hae-gwan (Lee Sung-min) is a middle-aged Korean man whose life has been shattered by the disappearance of his daughter. For over a decade, he has been wandering the country in search of her. Everyone he knows insists that she was killed in a tragic subway fire in Daegu, even though her body was never recovered. (The subway fire is a real-life event from 2003 that was incorporated into the film's plot.) But Hae-gwan insists that she ran away and is living somewhere on her own.

Meanwhile, Hae-gwan (Lee Sung-min) is a middle-aged Korean man whose life has been shattered by the disappearance of his daughter. For over a decade, he has been wandering the country in search of her. Everyone he knows insists that she was killed in a tragic subway fire in Daegu, even though her body was never recovered. (The subway fire is a real-life event from 2003 that was incorporated into the film's plot.) But Hae-gwan insists that she ran away and is living somewhere on her own.

Thus it is that Sori and Hae-gwan end up meeting on a deserted island beach off the Korean coast. Sori needs Hae-gwan's help to move around on land, particularly given that the machine's ultimate goal is to go to the Middle East. Hae-gwan, for his part, realizes that Sori's technology could help him find his daughter. The two become an unlikely team, searching across Korea and into past telephone records for a woman who seems to have vanished into thin air. But unbeknownst to them, various figures from the NSA, NASA and Korean intelligence services are searching desperately for the missing satellite.

Sori: Voice From the Heart is a film filled with surprises. One of the surprises is that a story so eccentric and outlandish should end up working so well. It's true that sometimes, such as in the climactic sequence, the film spins a bit out of control. Scenes involving US or Korean intelligence figures can also feel silly at times. Nonetheless, for all its shifts in tone, the emotions in this film feel real. That sense of authenticity comes from the fact that the filmmakers are pushing boundaries from a creative standpoint, and also because second-time director Lee Ho-jae (The Scam) proves willing to tackle difficult emotional issues, such as grief and loss, in a direct way. There's a genuine beating heart at the center of this film.

Another surprise is that a film featuring a banged-up spy satellite as its co-star should make for such engaging drama. Of course, those familiar with actor Lee Sung-min (Broken, Venus Talk), who after a long career as a supporting actor is now emerging into the spotlight, might be less surprised. Lee has tremendous range as an actor, including numerous roles as calculating villains (The Piper, A Violent Prosecutor), but he seems most effective in roles like this where he portrays an ordinary person dealing with ordinary (if very tragic) life experiences.

Other characters in the film are more colorful, from Lee Honey's role as a gifted, bilingual and compassionate scientist, to the more broadly comic performance turned in by Lee Hee-jun as her superior. (The latter excels at playing slightly deranged figures, such as the sex-starved Chang-wook in Haemoo or the scheming Hook in A Melody to Remember). When you look at all the pieces that make up Sori: Voice From the Heart, it seems inconceivable that they might all fit together to make a coherent movie. But somehow, director Lee manages to keep everything from flying apart, and the result is a truly original and engaging story. (Darcy Paquet)

The film opens with a hardworking female reporter Lee Hye-ri (Park Hyo-joo, Punch, The Chaser) lying in a coma with life-threatening wounds. The police and various new agencies attempt to unlock the mystery behind the circumstances in which a number of people, including Hye-ri's cameraman assistant Seok-hoon (Lee Hyun-wook, The Target), were brutally murdered at an isolated island, leaving Hye-ri as the only living witness. The key evidence is the interview footage left in Seok-hoon's camcorder, smashed but recovered later. As the main body of the film reconstructs the investigating reporter's attempts to penetrate the veil of secrecy that seems to permeate the island community, we learn that the island's main source of income, a salt harvesting business owned by the Heo family (Choi Il-hwa, New World, as the serpentine father and Ryoo Joon-yeol, Socialphobia, as the callous, violent son) might have been practicing modern-day slave labor. Hye-ri repeatedly approaches one of the salt-field workers, Sang-ho (Bai Song-woo, Veteran), who seems to be mentally disadvantaged and shows signs of severe physical abuse, and tries to get him to acknowledge on camera the horrid treatment he has been subject to. However, a check with Sang-ho's missing-person status leads to a shocking revelation for which neither Hye-ri nor Seok-hoon is prepared.

No Tomorrow is loosely based on an actual case in which a Cholla Province saltern owner was accused in 2014 of keeping dozens of workers, some suffering from mental and physical disabilities, under inhumanly abusive, slave-like conditions for years. Co-written and directed by Lee Ji-Seung, who had previously helmed the low-rent revenge thriller Azooma (2012), No Tomorrow starts off like a work-print for a "human rights"-oriented TV documentary, with Park Hyo-joo as Hye-ri enduring frustrations and hostilities from the island residents yet heroically persisting to obtain testimonies and evidence for the abuses visited on the salt field workers, especially Sang-ho, but abruptly transforms itself into a gory slasher with a somewhat predictable "plot twist."

Given its subject matter, the film is made in the by-now utterly conventional-looking "found-footage" style, with Seok-hoon's handheld HD camcorder dominating the viewer's POV. Except for occasional, air-clearing shots of beautiful beachfronts and surfs, everything Seok-hoon films looks suitably cruddy, grimy and oppressive: soon, the found footage gimmick becomes, what can I say, boring and exhausting, stripping the film of any emotional connection. As for the plot twist, while it does rescue the film to a certain degree from sinking into the swamp of torpor, it again reveals director Lee's inability to fully work out moral calculus of his project (as was the case with Azooma, one of those ethical-dilemmas-be-damned Korean thrillers that think they are scoring "progressive" political points, endorsing fantastically gory vengeances by the allegedly "powerless" victims). It did not seem to have occurred to him that screwing the film's trajectory like that in effect degrades the meaning of Hye-ri's hard work in the first half, reducing her to a pawn in the filmmaker's one-upmanship against the viewer's expectations.

Given its subject matter, the film is made in the by-now utterly conventional-looking "found-footage" style, with Seok-hoon's handheld HD camcorder dominating the viewer's POV. Except for occasional, air-clearing shots of beautiful beachfronts and surfs, everything Seok-hoon films looks suitably cruddy, grimy and oppressive: soon, the found footage gimmick becomes, what can I say, boring and exhausting, stripping the film of any emotional connection. As for the plot twist, while it does rescue the film to a certain degree from sinking into the swamp of torpor, it again reveals director Lee's inability to fully work out moral calculus of his project (as was the case with Azooma, one of those ethical-dilemmas-be-damned Korean thrillers that think they are scoring "progressive" political points, endorsing fantastically gory vengeances by the allegedly "powerless" victims). It did not seem to have occurred to him that screwing the film's trajectory like that in effect degrades the meaning of Hye-ri's hard work in the first half, reducing her to a pawn in the filmmaker's one-upmanship against the viewer's expectations.

Had Lee worked further on the screenplay, introducing more complexities and potentially contradictory features to the characters of Hye-ri, Sang-ho and the saltern owners, and explored with restraint the dynamics arising out of these characters with different social expectations, values and objectives, No Tomorrow still might not have worked, but would at least deserved greater respect. As it stands, the film is fundamentally uninvolving, not because its agendas are murky, but because its characterization is so thin.

It is not the cast's fault that the movie is so insipid: Park Hyo-joo is not really given a good role to play but she gamely rises to the occasion, conveying earnestness and drive, the kind that in a Korean professional woman can still provoke irrational antagonisms from men. Bae Song-woo is also fine as the beaten-down Sang-ho, taking care to dial down his patented reptilian bad-guy ticks and reaching for the viewer's pity, if not sympathy. Unfortunately, Bae's presence reminds us of his memorably villainous turn in Bedevilled (2010), a decidedly superior motion picture that shares some elements of the setting with the present film, but the comparison with which does the latter no favors.

No Tomorrow is not a complete wash, but is (again) unable to overcome one of the frustrating contradictions of the contemporary Korean thriller cinema: their post-Memories of Murder obsession with "documentary realism" actually render their characters cardboard-thin and, ultimately, lifeless. Korean screenwriters shooting for crime/topical thrillers, in my view, should stop worrying about "accurately capturing reality" and instead spend energy and time constructing rich fictional characters. (Kyu Hyun Kim)

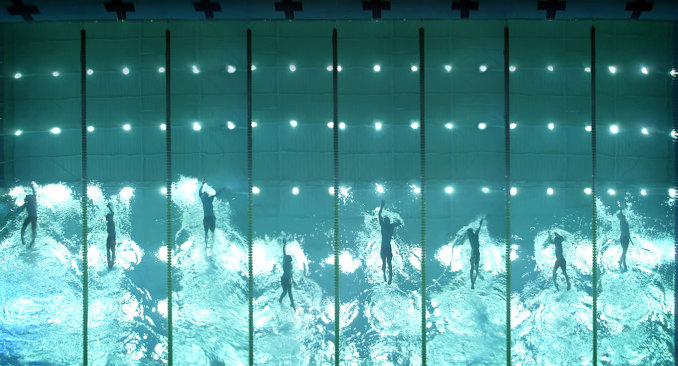

The 15-minute black-and-white segment that opens this film centers around a teenage swimming prodigy named Gwang-soo. Swimming at a pace far beyond any of his competitors, he is South Korea's greatest hope for medal glory in the upcoming Olympics. But underneath his cocky, self-assured exterior is a volatility and lack of judgement that causes conflict with his coach, and threatens his success.

Sixteen years later, Gwang-soo is contacted by a woman who asks him to coach her elementary-school aged son. The boy, Joon-ho, shows some talent for swimming, but in competitions he continually places 4th. Desperate to improve her son's performance and open up a path to a swimming scholarship, the mother seeks out Gwang-soo, despite his reputation for being unreasonably harsh to his students.

Jung Ji-woo's Fourth Place is a particularly impressive and thought-provoking work that stands out among recent Korean films. It's a story about parents, teachers and children, and more generally about the pressure placed on young children to succeed. How much pain and misery is worth enduring for a shot at success? And what is the line that separates pressure from abuse?

Jung Ji-woo's Fourth Place is a particularly impressive and thought-provoking work that stands out among recent Korean films. It's a story about parents, teachers and children, and more generally about the pressure placed on young children to succeed. How much pain and misery is worth enduring for a shot at success? And what is the line that separates pressure from abuse?

At first glance, Fourth Place looks like a film that will advance a certain argument about the issues it raises. The fact that it is produced and financed by the National Human Rights Commission of Korea only reinforces this first impression. But soon after the film starts, it becomes clear that Fourth Place is more nuanced than a simple issue film. It inspires you to think, but it does not tell you what to think.

The beating heart of the film are its well-rounded characters. There is a world of difference between the young, confident Gwang-soo who looks capable of anything, and the haunted, angry person he becomes later in life. Actor Park Hae-jun makes little effort to make his character likeable, but having seen what he was in his youth changes the way that we look at him. Yoo Jae-sang portrays Joon-ho as a quiet boy who nonetheless betrays hints of a rich inner life. At no time does he come across as a one-dimensional victim. Finally Lee Hang-na, who plays Joon-ho's mother, brings a desperate intensity to her performance that suggests how much pressure she herself feels in a society that surely ranks among the world's most competitive. One senses that she is causing harm to her son, but there is also love mixed in with her actions.

None of the film's leading actors are recognizable stars, which in this case seems to give the work a greater sense of authenticity. The convincingly ordinary setting and lesser degree of visual ornament is a change of pace for director Jung Ji-woo, who is accustomed to working on mainstream projects with major stars. But the artistic sensibility that is present in all of his films comes through particularly strong in Fourth Place, giving the work an unusual emotional intensity. He has taken advantage of the low-budget format to make a film that is more serious, but no less gripping, than a mainstream commercial feature.

Various studies indicate that South Korean schoolchildren are among the unhappiest in the world. So in Korea, the effort to make children feel happier is more than just a project for individual families, but a broader social and political issue. Fourth Place demonstrates many of the complexities and challenges involved in addressing this problem, but the very fact that it exists can perhaps serve as a note of encouragement. (Darcy Paquet)

A small town in Southwestern Cholla Province (named Gokseong, the homonym for the movie's Korean-language title, "the wailing voice," which is in real life one of the more beautiful tourist spots). Country cop Jong-gu (Gwak Do-won, Tazza: The Hidden Card)'s life is so uneventful that he has plenty of time to eat meals cooked by his nice wife (Jang So-yeon, Veteran) and help his precocious but charming ten-year-old daughter, Hyo-jin (Kim Hwan-hee, Night Fishing) prepare for school, before showing up at his patrol station. One day, however, an inhumanly gruesome murder takes place in the local herb and ginseng dealer's house, and Jong-gu and other cops are startled and unnerved by the murderer's otherworldly, zombie-like countenance, even though forensic analysis has pointed out the intoxication by hallucinogenic mushrooms as the likely reason for his berserk behavior. However, as the body count begins to multiply, Jong-gu and his colleagues become increasingly nervous and frightened. They come to give credence to the rumor that a Japanese old man (Kunimura Jun, Outrage), a local hermit, might have something to do with the strange goings-on. When Hyo-jin begins to show symptoms of possession (zombie-fication?), including inexplicable rashes, bouts of traumatic nightmares, and Regan-like shift of personality into a vicious, foul-mouthed tart, Jong-gu breaks down and seeks help from a charismatic shaman, Il-gwang (Hwang Jung-min, The Himalaya), who pegs the old Japanese as the Evil Spirit, and promises to exorcise him out of Hyo-jin's body. However, Jong-gu's nightmare has only begun as the cacophony of drums and gongs announce commencement of the ritual.

Na Hong-jin, whose The Chaser (2008) was one of the most impressive debut films in the history of New Korean Cinema, deeply divided the critical and public opinion with his sophomore effort Yellow Sea (2010), a criminal thriller that many thought were too relentless in its portrayal of human malevolence and misery. Having taken six years to prepare for his third film, however, Na has dialed down none of his signature intensity, nor sheer film-making hutzpah. The Wailing has already garnered among film critics and the movie-going public its share of I've-never-seen-anything-like-it shocked testimonies (Lee Dong-jin) as well as it's-all-smoke-and-mirrors denunciations and dismissals (most notably from Kim Young-jin), while handily conquering the spring-season box office with 6.78 million tickets sold as of June 15, 2016.

The Wailing is one of those genre-bound motion pictures that only South Korean filmmakers seem capable of putting together these days: an unholy marriage of the most vulgar, openly pulp-ish, garishly generic horror-thriller elements, on the one hand, and the kind of deceptively cerebral, diabolically manipulative film-making, goading its viewers towards existential despair or fundamental questioning of their conventional world-view, on the other, that would be regarded, in the North American market at least, as abjectly "art-house" and therefore inaccessible to most viewers. The brain-exploding theological/metaphysical questions generated by The Wailling have already compelled some American critics to compare it to the cinematic works of Luis Bunuel and Carl Dreyer: yet the same film features possibly the most emotionally harrowing and physically unnerving child-possessed-by-evil-spirit sequences since The Exorcist (1973), and a stupefyingly audacious (and darkly hilarious) zombie attack sequence worthy of George Romero's original Dead trilogy. Indeed, The Wailing is the kind of film George Romero at the height of his '70s prowess might have concocted, had he resolved to take inspirations from Shindo Kaneto's Onibaba (1964) or Kuroneko (1968) into the nuclear-fission extreme, if you could even imagine such a motion picture. And did I say how wickedly funny the movie is, in between the horror sequences enshrouded in the gradually suffocating atmosphere of dread?

The Wailing is one of those genre-bound motion pictures that only South Korean filmmakers seem capable of putting together these days: an unholy marriage of the most vulgar, openly pulp-ish, garishly generic horror-thriller elements, on the one hand, and the kind of deceptively cerebral, diabolically manipulative film-making, goading its viewers towards existential despair or fundamental questioning of their conventional world-view, on the other, that would be regarded, in the North American market at least, as abjectly "art-house" and therefore inaccessible to most viewers. The brain-exploding theological/metaphysical questions generated by The Wailling have already compelled some American critics to compare it to the cinematic works of Luis Bunuel and Carl Dreyer: yet the same film features possibly the most emotionally harrowing and physically unnerving child-possessed-by-evil-spirit sequences since The Exorcist (1973), and a stupefyingly audacious (and darkly hilarious) zombie attack sequence worthy of George Romero's original Dead trilogy. Indeed, The Wailing is the kind of film George Romero at the height of his '70s prowess might have concocted, had he resolved to take inspirations from Shindo Kaneto's Onibaba (1964) or Kuroneko (1968) into the nuclear-fission extreme, if you could even imagine such a motion picture. And did I say how wickedly funny the movie is, in between the horror sequences enshrouded in the gradually suffocating atmosphere of dread?

Some of the criticisms of the film are focused on the editorial tricks-- "cheats"-- director Na plays on the viewers, most importantly during the film's amazing center-piece, in which Il-gwang's flame- and blood-drenched, explosive exorcism rite, that radiate the kind of glittering, lip-smacking pagan beauty completely unlike any "respectful" shamanistic rite seen in, say, an Im Kwon-taek film, is cross-cut with the Japanese old man's cobweb-draped, mysteriously morbid "ritual," building to a horrifying crescendo (I would have gladly paid a $13 admission to just lay my eyes and ears on this gorgeous sequence). Many viewers will be led to assume a good-vs.-evil antagonistic relationship based on these narrative techniques, but Na pulls the rug out from under their feet at the last moment. Yet his sleight-of-hand is no conventional "plot twist," as he confronts the fallen-on-their-butts viewers with the possibility that Cunning of the Evil is ultimately triumphant in this world we live in, against the pitifully insignificant "goodness," too weak to be truly faithful, too stupid to rationally deal with such an overwhelming force: the moral deception perpetrated by the Evil on the hapless Jong-gu and other victims curling up inside the cinematic deception like a ice bar's sweet beans paste (Needless to say, an entirely opposite interpretation that emphasizes the tragic inability of the Korean characters, beginning with Jong-gu, to distinguish true Good from Evil, also makes sense). Na inexorably drives the film into the denouement both emotionally devastating and spiritually challenging, way beyond the usual target range of a commercial horror film. How can I put this properly? Watching The Wailing expecting something like Conjuring 2 is like ordering a can of Red Bull and instead imbibing a full glass of green, glowing absinthe laced with LSD. Oh, you will know that this baby is on many orders of magnitude something else, all right, but this does not guarantee that you will like it (or not feel cheated or manhandled by the director).

Now I would be lying if I insist that Na Hong-jin figured out how all the puzzle pieces of the plot perfectly fit together. There are a few areas where artful ambivalence tilts toward obscurantism: in particular, he stretches the "moral ambiguity" of Jong-gu and the villager's hostile attitude against the "Japanese stranger" near the breaking point, risking dropping the cake on the floor before even securing it in his hands, much less eating it (By the way, I totally reject the ludicrous "interpretation" that the events depicted in the film constitute an allegorical replay of Korea's colonial experience under the Japanese rule. Puhl-ease. To my chagrin, however, I am fully expecting someone to write an academic article on The Wailing based on that "reading." As far as I am concerned, the old stranger could have been ethnically and/or nationally American, Chinese or Viet Namese, and it would have made little difference).

In any case, in my view the film's Japanese stranger is one of the best roles written for a Japanese actor in a Korean motion picture, even if it may seem to some viewers to be "justifying" the obsessive Korean racism against their neighboring citizens. Kunimura Jun is brilliant as the stranger, by turns imposing, menacing and sympathetic, yet always gently enigmatic (Kitano Takeshi was allegedly Na's first choice for the role. I am glad that it was eventually offered to Kunimura. His characteristic "warmness," as opposed to Kitano's steely poker-face, brings another layer of interest to the role). Other Korean actors also deliver proverbially "possessed" performances. Hwang Jung-min drives the narrative full-throttle as the charismatic, loud-mouthed shaman, perfectly counterpointing Chun Woo-hee's creepily subdued interpretation of another mysterious presence, whose intentions are never entirely transparent to the viewers, despite her helpful gestures toward Jong-gu. Gwak Do-won, long been cast as smarmy bureaucratic villains in films such as The Faceless Gangster (2011) and The Berlin File (2012), is riveting and ultimately heartbreaking as the protagonist Jong-gu, the audience surrogate who is perhaps too common-sensical and harried by everyday life to contemplate the irrationality of the Evil befallen on his hometown. But even Gwak and Hwang's powerful performances have to take back seats to the beautifully expressive one delivered by the child actress Kim Hwan-hee as Hyo-jin, which provides the crucial emotional anchor to the horrific proceedings.

As Lee Dong-jin points out, Na Hong-jin is so totally in control of every frame that the film ironically generates an aura of rock-solid reliability, even though one of its themes may be powerlessness of the ordinary human beings against the chaotic nature of the universe. There is not a millimeter reel of sparing gesture, hesitation, or second-guessing in The Wailing. Na simply pushes, pushes ahead, and still pushes the envelope like a toro bravo, until it is torn apart and rendered like a piranha-devoured deer carcass. Moreover, few films I have seen this year can boast the incredible handiworks of DP Alex Hong Gyeong-Pyo, perhaps my all-time favorite Korean cinematographer and responsible for Snowpiercer, Mother and Save the Green Planet, and Lighting Supervisor Kim Chang-ho (Haemoo), capturing the majestic beauty of the unsullied natural landscape of the South Cholla Province, as well as the scenes of supernatural terror in their paradoxically gorgeous decrepitude. From the veteran Kim Sun-min's (Yellow Sea, The Host) editing to production design, special effects, sound design and to Jang Young-gyu and Dal Pa-ran's (Assassination, The Thieves) restrained but effectively eerie score, all elements of the production are top-notch and firmly under the director's control.

As Lee Dong-jin points out, Na Hong-jin is so totally in control of every frame that the film ironically generates an aura of rock-solid reliability, even though one of its themes may be powerlessness of the ordinary human beings against the chaotic nature of the universe. There is not a millimeter reel of sparing gesture, hesitation, or second-guessing in The Wailing. Na simply pushes, pushes ahead, and still pushes the envelope like a toro bravo, until it is torn apart and rendered like a piranha-devoured deer carcass. Moreover, few films I have seen this year can boast the incredible handiworks of DP Alex Hong Gyeong-Pyo, perhaps my all-time favorite Korean cinematographer and responsible for Snowpiercer, Mother and Save the Green Planet, and Lighting Supervisor Kim Chang-ho (Haemoo), capturing the majestic beauty of the unsullied natural landscape of the South Cholla Province, as well as the scenes of supernatural terror in their paradoxically gorgeous decrepitude. From the veteran Kim Sun-min's (Yellow Sea, The Host) editing to production design, special effects, sound design and to Jang Young-gyu and Dal Pa-ran's (Assassination, The Thieves) restrained but effectively eerie score, all elements of the production are top-notch and firmly under the director's control.

The Wailing is an extremely welcome throwback to the boldly experimental and yet hellaciously entertaining Korean cinema of early 2000s, when filmmakers like Park Chan-wook, Kim Ji-woon and Bong Joon Ho would grab hold of tired genre clichés and transmute them into striking, sui generis works of art such as Memories of Murder, A Tale of Two Sisters and Oldboy. Of course, it is one serious mind-f*cking crazy-yahoo horror film of the year, too, but that observation is almost an icing on the cake that is this jaw-droppingly-beautiful, extremely-well-acted, seriously-messing-with-your-brain radioactive isotope of a movie.

I am no crystal ball reader but I have little problem predicting that The Wailing will be obsessed over by many filmmakers and film fans, many years into the foreseeable future, generating at least one English-language remake in the meantime (how about one directed by Alfonso Cuaron, set in the nineteenth century Spanish-speaking California, with the "stranger" played by Javier Bardem� Santo cielo, try to imagine that movie), and eventually stand tall as one of the unkillable fighting bulls of 2010s movie scene, whilst its other film-festival- and critic-beloved contemporaries have faded into the grey backdrop. (Kyu Hyun Kim)

A wet day, in a colonial Korean city, circa 1930s: as a regiment of Japanese soldiers march through the shower, Sook-hee (newcomer Kim Tae-ri), is tearfully sent off to work for a "Jap" household: yet looks can be deceiving. It turns out that Sook-hee has lived for years as a seasoned pickpocket and a fence, trained among an ersatz family of con artists. Once sent to the household of Kozuki (Jo Jin-woong, A Hard Day [2013], Hwayi: A Monster Boy [2013]), a monstrously wealthy Korean collaborator obsessed with collecting classic erotica, Sook-hee is made to serve as a handmaiden of the old man's niece Hideko (Kim Min-hee, Helpless [2012], Right Now, Wrong Then [2015]), the heir to the gold mine fortune of the household. The plan is for an oily Korean charlatan Count (Ha Jung-woo, Assassination [2015], Tunnel [2016]) to approach Kozuki, impersonating a titled Japanese cad and fellow enthusiast for erotica collection (and their, er, re-enactments), and then seduce Hideko, eventually eloping with her for a shotgun marriage. Entrusted with the task to gently nudge the virginal Hideko toward the groping hands of the Count, Sook-hee at first complies, but soon begins to have second thoughts, as she begins to fall for Hideko, an ethereal beauty who is not what she appears to be either.

The Handmaiden is based on Sarah Walter's Fingersmith, nominated for the Booker Prize despite its up-front genre pedigree as well as a powerfully sensual lesbian relationship at its center. Certainly not an easy work to adapt into a Korean setting, and not just because of (hypocritical) sexual conservatism on the part of the mainstream Korean society, the source novel is handled by director Park Chan-wook (taking directorial reins of a Korean-language production again, after the reasonable critical success of the English-language thriller Stoker [2013]) and his longtime screenplay partner Jeong Seo-gyeong, with respect, but not deference. Of course, this being a Park Chan-wook film, the fans need not worry about being handed a watered-down Masterpiece Theater adaptation: the envelope-pushing transgressive allure of the original is carried over intact into the movie version, along with the ingeniously creative transliteration of the Victorian British perversities into the early modern Japanese ones. The Handmaiden comes across as neither coy and coquettish nor prim and corseted but open and solid, willing to let emotional gyroscopes of the main characters navigate the narrative.

Reunited with many key staff members from Thirst (2009), DP Chung Chung-hoon (Boulevard [2014], New World [2012]), production designer Ryoo Seong-hee (Assassination, Ode to My Father [2014]), costume designer Jo Sang-gyeong (The Royal Tailor [2014], The Tiger [2015]) and composer Jo Young-wook (Hide and Seek [2013], Gangnam Blues [2014]), Park, making use out of the film's colonial setting, freely construct a world at once eye-poppingly luxuriant and luridly decadent, yet not letting go of a form of aesthetic dignity. Kozuki's library and reading room for the various erotica he has collected throughout the world present themselves as an impossible hybrid of a sprawling bunraku theater and a James Bond villain's lair. Some of the set-pieces attain qualities of genuine artistic delirium reminiscent of the taboo-breaking '60s and '70s genre cinema from Japan, e.g. feverish yet cool genre excursions of Masumura Yasuzo or Suzuki Seijun.

Reunited with many key staff members from Thirst (2009), DP Chung Chung-hoon (Boulevard [2014], New World [2012]), production designer Ryoo Seong-hee (Assassination, Ode to My Father [2014]), costume designer Jo Sang-gyeong (The Royal Tailor [2014], The Tiger [2015]) and composer Jo Young-wook (Hide and Seek [2013], Gangnam Blues [2014]), Park, making use out of the film's colonial setting, freely construct a world at once eye-poppingly luxuriant and luridly decadent, yet not letting go of a form of aesthetic dignity. Kozuki's library and reading room for the various erotica he has collected throughout the world present themselves as an impossible hybrid of a sprawling bunraku theater and a James Bond villain's lair. Some of the set-pieces attain qualities of genuine artistic delirium reminiscent of the taboo-breaking '60s and '70s genre cinema from Japan, e.g. feverish yet cool genre excursions of Masumura Yasuzo or Suzuki Seijun.

Of course, Park's dazzling stylistics and firm command of the twists and turns of the plot are very much in evidence here: as is the case with Park's Joint Security Area (2000), split POVs of the narrative allow each main character to shine in his or her revelatory moments. Yet The Handmaiden is iconically owned by Kim Min-hee, whose poker-face portrayal of Hideko sets the tone for the entire movie, subtly affecting without affectation. Wrapped up in splendiferous kimono fashions and statuesque kabuki makeup, and staring dreamily into the infinite edge of the horizon, Kim cuts a striking, mesmerizing figure, but she is also a sinuously expressive actress, capable of shocking (male) viewers with the eruption of raw disgust at the Count's date-rape routine. Coltish Kim Tae-ri, cast to appeal to more contemporary young Korean women (a total success in that regard), is best when she essays psychological confusion, when confronted by an alluring mystery in the form of her "mistress:" some of the film's best scenes involve Sook-hee's growing identification with Hideko, whom she initially sees as utterly naïve and powerless, a living doll. Despite the inevitable accusation likely to be leveled at Park for his "male gaze," Kim Min-hee and Kim Tae-ri succeed in making their attraction to one another feel emotionally authentic for the viewers, male or female: haltingly and breathlessly articulated mixtures of identification, compassion, petty jealousy and, yes, unbridled, I-wanna-f*ck-you-right-now lust.

It is not surprising that the film's male characters suffer in comparison to these luminous creatures. Jo Jin-woong, who has to recite almost all of his dialogue in deliberately quaint "literate" Japanese, gives the old man's slobbering madness an appropriately eccentric spin, but Ha Jung-woo, one of Korea's biggest film stars today, is utterly miscast as the Count. His characterization stops at just endowing the Count little more than a huge male ego, missing a chance to bring richness to the layers of motivations and internal strife of the character. Ha, a fine actor in a contemporaneous every-guy role like the main victim in Tunnel, is simply not convincing as a Korean con artist suavely pretending to be a '30s Japanese aristocrat. A more ironically neurotic, svelte interpretation, rather than physical attractiveness, would have greatly enhanced the character's presence, especially in the third part of the film.

A note on the complicated linguistic scheme of the film: even though the majority of dialogue in the film is in Japanese, most of them are spoken by Korean actors (English subtitles of the North American theatrical print divides the Japanese and Korean languages by rendering the former in yellow, the latter in white, an excellent idea), except for a few minor roles such as asylum doctors and nurses. Consequently, few of the dialogue heard in the film would strike a native Japanese viewer as "authentic."

Is this possibly a serious problem? The answer is actually pretty complicated. One notices that each main character of The Handmaiden is bilingual, but for different reasons: Kozuki is a native Korean grotesquely aspiring to be an authentic Japanese man of letters: the Count is a Korean commoner pretending to be a noble Japanese: Hideko is a native Japanese who has lived in Korea since she was ten and picked up Korean as a second language along the way: and Sook-hee is a Korean girl who simply has learned Japanese well as a tool of the trade. It is perhaps amusing, then, that, at least to my (Full disclosure- I am also a native Korean speaker who has been teaching Japanese history and culture for twenty years) ears, Sook-hee's Japanese sounds most natural, followed by Hideko's, Kozuki's and the Count's in the order of competence (or believability). Kim Min-hee's occasionally iffy Japanese pronunciation can be tolerated in terms of the plot contrivance, although even a ten-year-old Japanese girl who had "naturalized" to Korean life would probably not command Korean perfectly like Hideko does in the film. On the other hand, there is just no way a shrewd devil like Kozuki could mistake Ha Jung-woo's Count for a "real" Japanese, unless of course his own command of Japanese language is a mess (not an impossible scenario, strictly speaking). Most of the time when Ha has to deliver in Japanese some supposedly sophisticated speeches on the European literary tradition or whatnot, or croon embarrassingly "romantic" dialogues to Kim Min-hee, I am afraid I was taken right out of the movie. Would the result have been much worse, if a Japanese star, Nagase Masatoshi or Kimura Takuya, perhaps, was cast as the Count and phonetically learned the film's Korean dialogue?

Is this possibly a serious problem? The answer is actually pretty complicated. One notices that each main character of The Handmaiden is bilingual, but for different reasons: Kozuki is a native Korean grotesquely aspiring to be an authentic Japanese man of letters: the Count is a Korean commoner pretending to be a noble Japanese: Hideko is a native Japanese who has lived in Korea since she was ten and picked up Korean as a second language along the way: and Sook-hee is a Korean girl who simply has learned Japanese well as a tool of the trade. It is perhaps amusing, then, that, at least to my (Full disclosure- I am also a native Korean speaker who has been teaching Japanese history and culture for twenty years) ears, Sook-hee's Japanese sounds most natural, followed by Hideko's, Kozuki's and the Count's in the order of competence (or believability). Kim Min-hee's occasionally iffy Japanese pronunciation can be tolerated in terms of the plot contrivance, although even a ten-year-old Japanese girl who had "naturalized" to Korean life would probably not command Korean perfectly like Hideko does in the film. On the other hand, there is just no way a shrewd devil like Kozuki could mistake Ha Jung-woo's Count for a "real" Japanese, unless of course his own command of Japanese language is a mess (not an impossible scenario, strictly speaking). Most of the time when Ha has to deliver in Japanese some supposedly sophisticated speeches on the European literary tradition or whatnot, or croon embarrassingly "romantic" dialogues to Kim Min-hee, I am afraid I was taken right out of the movie. Would the result have been much worse, if a Japanese star, Nagase Masatoshi or Kimura Takuya, perhaps, was cast as the Count and phonetically learned the film's Korean dialogue?

Nonetheless, I want to reassure you that this linguistic hybridity in The Handmaiden is really not a serious obstacle for most viewers, especially if you are following the plot via English subtitles. Identity gymnastics aside, it is refreshing to see a Korean film that refuses to evade the reality concerning the co-mingling of Japanese and Korean cultures under the colonial conditions.

The Handmaiden, set to open in North American theaters in October 21, 2016, had given its producers some heartburn prior to its June 1 domestic release, thanks to its heavily sexual content (making an adult-only viewer restriction an inevitability) and its predominantly Japanese dialogue, but the Korean viewers, especially the crucial young female demographic, by and large embraced the film, allowing it to rake in 4.29 million tickets. Not quite a portentous art-house heavyweight, but not nearly the cotton-candy bodice-ripper some reviewers have made it out to be either, The Handmaiden, amidst its considerable package of genre thrills, holds tight onto a core of affective energy generated by the terrific chemistry between its two leading actresses. (Kyu Hyun Kim)

Sun is a 10-year old girl who feels deeply uncomfortable at school. The other girls in class, particularly top student Bora, are mean to her, and there's no one she can count on to be her friend. But soon after the start of summer vacation, she happens to meet Jia, another girl the same age who has just moved into her neighborhood. Jia is smart and resourceful, and she and Sun quickly become friends. Jia seems reluctant to invite Sun to her place, where she lives alone with her grandmother, but the two of them spend a lot of time at Sun's home, sometimes watching over her younger brother. For the space of a summer, Sun feels content and relieved at having found a good friend.

But things change when school re-starts, and Jia joins Sun's class. Now Jia has to find her place within the social circles at school, and new pressures are placed on their friendship. Jia also joins one of the after-school study institutes where so many Korean middle and upper class students receive extra instruction. Sun's family can't afford it, and this introduces another kind of distance between them. In the coming months, Sun and Jia's friendship will be tested in ways that they never expected.

Yoon Ga-eun's debut feature, coming on the heels of two highly acclaimed, award-winning shorts Guest (2011) and Sprout (2013), is appropriately titled. The World of Us does not present the lives of its young protagonists from the perspective of a nostalgic adult looking back on childhood. Instead, it depicts the complicated emotions of these girls with such nuance and intimacy that we feel pulled into their world. Since the director treats Sun's anxiety and Jia's insecurity with total seriousness and respect, we too come to think of them more as equals than of children with limited life experience. At the same time, we also feel how the weaknesses and troubles of the parents press down on the girls' lives.

Yoon Ga-eun's debut feature, coming on the heels of two highly acclaimed, award-winning shorts Guest (2011) and Sprout (2013), is appropriately titled. The World of Us does not present the lives of its young protagonists from the perspective of a nostalgic adult looking back on childhood. Instead, it depicts the complicated emotions of these girls with such nuance and intimacy that we feel pulled into their world. Since the director treats Sun's anxiety and Jia's insecurity with total seriousness and respect, we too come to think of them more as equals than of children with limited life experience. At the same time, we also feel how the weaknesses and troubles of the parents press down on the girls' lives.

For a film like this to really work requires the vision and passion of the director, but also a good deal of talent from the young cast. The actresses who play Sun (Choi Soo-in), Jia (Seol Hye-in) and Bora (Lee Seo-yeon) are not the sort of highly trained, professional child actors that you see in many Korean films these days. None of them had previously acted in a film of this scale, but Director Yoon managed through extensive rehearsals and some clever techniques to draw out highly natural performances from the girls. Each of the three protagonists are as fully developed and nuanced as any adult characters you'll see in other films. Choi Soo-in in particular projects a delicate but resilient emotional core that makes Sun a fascinating character.

In her films to date, Director Yoon has also shown a good feel for space and community. Shot in various neighborhoods in northern Seoul, the film's setting is not particularly unusual, but it is memorable thanks to the naturalistic way it's presented. At no time does it feel like a location or set is meant to project a certain atmosphere; instead, it just feels convincing.

Sometimes people use the term "small film" to describe works shot on this scale, and while it's true that this is a film about small people, there's nothing small about the emotions and ambitions of this work. It's a truthful film that contains insight for viewers of any age. And it tells its story with both elegance and intelligence. Movies like this don't come around often. The World of Us is a quiet triumph. (Darcy Paquet)

Yeon-hong (Son Ye-jin, Blood and Ties, The Classic) is a beautiful housewife married to the dashing politician Kim Jong-chan (Kim Joo-hyuk, The Beauty Inside, Singles), a Hanguk Party (an obvious stand-in for the real-life ruling party, Saenuri) rookie facing a tough competition against an unaffiliated veteran, No Jae-soon (Kim Eui-seong, Train to Busan). When her teenage daughter Min-jin (Shin Ji-hoon) disappears on the way to the school, no one takes it seriously, except for Yeon-hong, who, despite working hard to outwardly maintain the image of the Good Wife, becomes increasingly paranoid and furious (the fact that she is constantly reminded of her Jeolla Province background by the opposition and surrounded day and night by the virulently chauvinistic Party operators certainly does not help the matters). When Min-jin refuses to turn up even after three days, she suspects some dirty machinations from the oily No, but the police and her husband are of course not inclined to indulge her "conspiracy theories." As Yeon-hong doggedly investigates the circumstances surrounding her daughter's sudden disappearance, the situation shifts from worrisome to abjectly horrifying, as she finds not only evidence for systematic bullying of her daughter as well as a twisted plot involving Min-jin's pretty teacher Son So-ra (Choi Yu-hwa, Worst Woman), but also the utterly unwelcome, devastating truths about the lives of her daughter, her husband and herself.

Tightly plotted as a mystery thriller, The Truth Beneath is a sophomore effort by the Park Chan-wook protégé Lee Kyoung-mi who previously helmed Crush and Blush (2008), a quirky indie vehicle for Gong Hyo-jin depicting an unusual relationship that develops between a socially inept, emotionally unstable schoolteacher and her equally mal-adjusted teenage disciple. Unfortunately, The Truth Beneath did not do well at the box office (250K tickets sold by August 2016) and sharply divided critics as well. The film reminded some viewers of Park Chan-wook's Revenge trilogy in terms of its seemingly incongruous combination of aggressive stylistics and hard-boiled, vicious content, as well as Nakashima Tetsuya's The World of Kanako (2014), another revenge thriller pivoting around the disappearance of a teenager and her parents' desperate search for her, but these resemblances are largely superficial. Lee's direction does evoke her mentor's in his Sympathy for Mr. Vengeance (2002) for its almost Old Testament approach to the hypocrisies and sins of the powerful and moneyed (here, parents and adults such as schoolteachers) resulting in the visitation of cruelties and tragedies on the powerless (here, mostly children), but her film is perhaps a truer film noir than Park's masterpiece, devoid of the deliberately symmetrical sense of the absurd permeating the latter, making it less philosophically or ethically challenging, but emotionally just as devastating and mysterious.

I must warn that The Truth Beneath could be extremely off-putting to some viewers who come for the wrong kind of movie. I would advise you not to expect a more typical kind of Korean thriller aiming to "expose" the conservative politicos, Big Business honchos and the legal-surveillance apparatuses (prosecutors, NIS, police, etc.) under their influence as corrupt, venal and anti-democratic. To be sure, director Lee does present persuasive vistas of Kim Jong-chan's aids, advisers, lawyers and other related parties mulling over Mi-jin's disappearance, trying out a variety of scenarios and coldly engaging in the calculus of positives and negatives of the fallout for their candidate, but her directorial interest does not lie in mining Sidney Lumet or Alan J. Pakula territory. She instead focuses on Yeon-hong's progressively extreme efforts to uncover the truths behind Min-jin's disappearance on her own.

I must warn that The Truth Beneath could be extremely off-putting to some viewers who come for the wrong kind of movie. I would advise you not to expect a more typical kind of Korean thriller aiming to "expose" the conservative politicos, Big Business honchos and the legal-surveillance apparatuses (prosecutors, NIS, police, etc.) under their influence as corrupt, venal and anti-democratic. To be sure, director Lee does present persuasive vistas of Kim Jong-chan's aids, advisers, lawyers and other related parties mulling over Mi-jin's disappearance, trying out a variety of scenarios and coldly engaging in the calculus of positives and negatives of the fallout for their candidate, but her directorial interest does not lie in mining Sidney Lumet or Alan J. Pakula territory. She instead focuses on Yeon-hong's progressively extreme efforts to uncover the truths behind Min-jin's disappearance on her own.

The point here is that Yeon-hong does not behave like typical tragic mother-heroines in genre films of this type: she displays neither Sally Field-like righteousness nor Julia Roberts-like vulnerability. Yeon-hong, like the always-blushing schoolteacher in Crush and Blush, turns out to be an almost-scary obsessive, the kind of person who would invite snorting derision from well-connected upper-crust members of society for being reckless and "inconsiderate." Ironically, Lee's dense but clear-eyed screenplay posits that it is her seeming lack of "maturity"-- which, in the context of the film, means knowing when to stop before causing some trouble (what Japanese would call meiwaku) for other proper members of society-- that allows her to see through the pretenses of Min-jin's classmates and penetrate various sub-groups closed to the outsiders. Yeon-hong fights tooth and nail against the police, her husband's aides, uncooperative kids, including Min-jin's erstwhile best friend, Mi-ok (Kim So-hee), who has the expressive capacity of a moon jellyfish, and of course her husband, Jong-chan: we have seldom seen such a determined yet ill-fitting detective figure not just in Korean films, but in contemporary motion pictures, period. Yet Lee and Son Ye-jin together manage to make her character work: Yeon-hong is absolutely compelling, even if she is not always sympathetic, or even accessible.

Indeed, the film feels so extreme partly because one keeps waiting for life-affirming, love-conquers-all, forgive-us-we-have-been-bad-parents, wailing confessions or some such reassuringly TV-drama-like, melodramatic moments and they never materialize. Director Lee stages various scenes of emotional display in such ways to blatantly undermine their melodramatic effects, yet to keep their lacerating powers intact: a funeral procession that sonically isolated Yeon-hong from other attendees, or the explosive fight between Yeon-hong and Jong-chan that veers perilously between exchanges of full-frontal violence and moments of acknowledgement of guilt and indifference as raw as exposed knife wounds, and so on.

It was a good move on Lee's part to cast Son Ye-jin in Yeon-hong's role. This was obviously a break that the latter was looking for as an actress: Son reigns in tear-jerking emotional outbursts that marred such other substantial roles as the beleaguered daughter of a kidnapper in Blood and Ties (2013), and delivers what is probably the best performance of her career. Son breathlessly but unerringly conveys the spiritual calluses developed from years and years of put-down, the suppressed but active intelligence and the raw empathic capacity of a Korean woman from a disadvantaged background yet cursed with the beauty that make men around her drool over her and at the same time denigrate her intelligence and integrity. Matching her performance blow by blow, Kim Joo-hyuk is equally well cast and excellent as Jong-chan, cool and calculating yet thoroughly human-scaled: as is the case with Yeon-hong, most viewers will find themselves unable to throw stones at the slick politician despite all the terrible plot revelations.

Is The Truth Beneath more than a just competent thriller? Darn yes. In some ways, I feel that it showcases the inimitable aspects of contemporary Korean genre cinema better than The Wailing (2016). While I feel that director Lee's full command of the film's wildly shifting tones and dazzlingly dense narrative deserves much praise, I also was strangely unmoved by the conclusion of the film. Partly it may be because, unlike the protagonists of Bedevilled (2010) or A Girl at My Door (2014), to cite two recent examples, I found the film's characters more fascinating than sympathetic, including the victimized children. In fact, The Truth Beneath comes across to me as one movie that gets at the rotten core of Korean society, not because it blames corrupt politicians (Donald Trump, anyone?), indifferent police (like all good Korean movies, The Truth Beneath refuses to caricature the police, incompetent or otherwise), or an educational system that reproduces economic and social hierarchies over multiple generations (where are the Whispering Corridors ghosts when we need them?), but because it unflinchingly shows the upper-middle Korean family as they really are: highly sophisticated, media-saturated, smart and pretty predators, insectoid, nest-forming, like gigantic, cannibalistic beetles with jeweled carapaces, that raise their grubs so that they can mature into equally sophisticated, media-saturated, smart and pretty predators.

Is The Truth Beneath more than a just competent thriller? Darn yes. In some ways, I feel that it showcases the inimitable aspects of contemporary Korean genre cinema better than The Wailing (2016). While I feel that director Lee's full command of the film's wildly shifting tones and dazzlingly dense narrative deserves much praise, I also was strangely unmoved by the conclusion of the film. Partly it may be because, unlike the protagonists of Bedevilled (2010) or A Girl at My Door (2014), to cite two recent examples, I found the film's characters more fascinating than sympathetic, including the victimized children. In fact, The Truth Beneath comes across to me as one movie that gets at the rotten core of Korean society, not because it blames corrupt politicians (Donald Trump, anyone?), indifferent police (like all good Korean movies, The Truth Beneath refuses to caricature the police, incompetent or otherwise), or an educational system that reproduces economic and social hierarchies over multiple generations (where are the Whispering Corridors ghosts when we need them?), but because it unflinchingly shows the upper-middle Korean family as they really are: highly sophisticated, media-saturated, smart and pretty predators, insectoid, nest-forming, like gigantic, cannibalistic beetles with jeweled carapaces, that raise their grubs so that they can mature into equally sophisticated, media-saturated, smart and pretty predators.

The bottom line is that I could not relate to the children, the ostensible victim figures, in The Truth Beneath. To be blunt, they are monsters, too, all too happy to prey on the vulnerable and the weak, in order to "protect" "their" vulnerable and weak. If Director Lee intended the very last scene of the movie to impart the point to the viewers that the children, at least Mi-ok, retained some "purity" unsullied by the adult-infested jungle around them, as some critics have argued, I must say it strikes me as rather feeble, if not insincere. It is one of the rare moments that felt tacked-on in a film brimming with horrific yet hypnotically compelling imagery and dialogue, those one almost subconsciously feels are getting at the deeper truths that the more critically successful auteurist vehicles and ten-million-tickets-sold blockbusters would rather not touch with a ten-feet pole. (Kyu Hyun Kim)

Hedge-fund trader Seok-woo (Gong Yoo, The Suspect) lives in a posh apartment with his mother and a ten-year-old daughter (Kim Soo-an, Coin Locker Girl), who is well aware that her parents have become estranged. Feeling guilty, Seok-woo reluctantly agrees to accompany his daughter in her trip to see her mother in Busan, via the bullet train KTX. In the train he encounters a group of high school baseball players, with teenage lovebirds Jinhee (So-hee, Hellcats) and Young-guk (Choe Woo-sik, Secretly, Greatly) as well as a newlywed couple, burly Sang-hwa (Ma Dong-seok, a.k.a. Don Lee, Deep Trap, The Chronicles of Evil) and very pregnant Seong-gyung (the cult actress Jeong Yoo-mi, Our Sunhi, Chaw). They pay little attention to the TV and internet news flashes of strange riots breaking out in various regions. Until one teenage girl, her skin covered with black-and-blue veins and gnashing teeth with insane fury, runs into the just-departed train, and bites a conductor. Soon, the conductor begins to show the same symptoms. There is no room to hide from the exponentially expanding number of milky-white-eyed, fast-moving zombies in the KTX train, dashing at 155 miles per hour, non-stop!

So begins one of the most unexpected genre offerings from South Korea in recent years, a full-blown zombie action-horror directed by Yeon Sang-ho, the culprit behind The King of Pigs and The Fake, gut-wrenching and bone-cracking animated features that were at the same time unflinchingly horrifying portraits of the hypocrisies and emotional violence of contemporary Korean society. As it turned out, Yeon has made back-to-back with this live-action film a companion piece, another animated feature titled Seoul Station, selected as the closing film for the 2016 Bucheon Fantastic Film Festival and slated to open in national theaters on August 18. Meanwhile, Train to Busan, released on July 20, had already chomped down chunks of the box office, having sold 9.5 million tickets in a little over two weeks. Seoul Station depicts the outbreak of the zombie epidemic in the eponymous location, and thus might be considered a prequel of sorts to the present film (the above-mentioned Train to Busan's No. 1 zombie, played by Shim Eun-gyung [Sunny, Possessed], is a much more substantial character in the animated feature).

Knowing the kind of merciless, almost cruel, disposition Yeon has toward his characters, it is both a relief and a strange letdown to realize that Train to Busan has no desire to twist its genre-derived elements beyond recognition. Make no mistake, however: we are talking about Korean genre filmmakers with the talent and moxie to take on competition many times their size. Just as The Wailing blows the skullcaps off any garden-variety possessed-by-the-devil horror opus, Train to Busan stomps to death those anemic, imagination-challenged zombie flicks that have become a staple of low-budget horror since the conclusion of George Romero's Dead trilogy (all of which have themselves been remade more than once by other filmmakers). The film combines the Hollywood-style approach of piling up ingeniously conceived and professionally executed set-pieces on top of another, and the more East Asian sensibility of preference for CGI-eschewing, physically in-there action and bold-faced melodramatics, into a winning formula. World War Z may have commanded a bigger scale, but its computer-rendered human hills of scrambling zombies have nothing on, for instance, the jaw-dropping raw stunt in Train's climactic chase sequence, showing dozens of zombies forming a ghastly sheet of human carpet behind a running train. Equally impressive is Yeon's total control over complex action set-pieces, making great use of usually mundane spaces such as the washroom and the luggage compartments, or routine situations such as the train entering tunnels at certain points, highlighted by the superb sequence in which our surviving protagonists, led by Seok-woo and Sang-hwa and armed with a baseball bat, a riot policeman's shield and the knuckles tightly wrapped in duct tape, must pass through a car full of the drooling, blood-thirsty infected. It is surely one of the best we-have-to-bust-a-few-zombie-heads-to-save-loved-ones sequences ever committed to celluloid (or digital pixels), striking the perfect balance between adrenaline-pumping excitement and heart-stopping thrills.

Knowing the kind of merciless, almost cruel, disposition Yeon has toward his characters, it is both a relief and a strange letdown to realize that Train to Busan has no desire to twist its genre-derived elements beyond recognition. Make no mistake, however: we are talking about Korean genre filmmakers with the talent and moxie to take on competition many times their size. Just as The Wailing blows the skullcaps off any garden-variety possessed-by-the-devil horror opus, Train to Busan stomps to death those anemic, imagination-challenged zombie flicks that have become a staple of low-budget horror since the conclusion of George Romero's Dead trilogy (all of which have themselves been remade more than once by other filmmakers). The film combines the Hollywood-style approach of piling up ingeniously conceived and professionally executed set-pieces on top of another, and the more East Asian sensibility of preference for CGI-eschewing, physically in-there action and bold-faced melodramatics, into a winning formula. World War Z may have commanded a bigger scale, but its computer-rendered human hills of scrambling zombies have nothing on, for instance, the jaw-dropping raw stunt in Train's climactic chase sequence, showing dozens of zombies forming a ghastly sheet of human carpet behind a running train. Equally impressive is Yeon's total control over complex action set-pieces, making great use of usually mundane spaces such as the washroom and the luggage compartments, or routine situations such as the train entering tunnels at certain points, highlighted by the superb sequence in which our surviving protagonists, led by Seok-woo and Sang-hwa and armed with a baseball bat, a riot policeman's shield and the knuckles tightly wrapped in duct tape, must pass through a car full of the drooling, blood-thirsty infected. It is surely one of the best we-have-to-bust-a-few-zombie-heads-to-save-loved-ones sequences ever committed to celluloid (or digital pixels), striking the perfect balance between adrenaline-pumping excitement and heart-stopping thrills.

Neither does Yeon forget to tend to his characters. Granted, they are not as thrillingly (and sometimes disturbingly) literary and original as in his previous films and come off as more genre archetypes than real people. Still, I must disagree with the criticism that he relies on hackneyed tear-jerking plot developments, especially during the final third. True, perhaps he should not have entrusted Gong Yoo with too many "moving" close-ups, but overall I support Yeon's decision not to assume the worst about human nature (except for the film's one true hissable villain Yong-seok [Kim Eui-seong, The Priests]: but even he has a strangely touching moment when he reverts back to the memory of a childhood trauma, just before the zombie virus takes over his brain completely). And I like it in Korean movies when characters break down and weep for having failed to save their loved ones, or overwhelmed by survivor's guilt: who's to say this is less "realistic" than the kind of we-have-a-job-to-do stoicism often displayed by the protagonists of American genre films? In any case, Ma Dong-seok delivers more than enough witty one-liners and smashes more zombie heads and noggins for any single feature.

Ma, Jeong and especially the child actress Kim should receive much kudos for perfectly pitching their performances at the slightly but not obviously exaggerated, feverish level that director Yeon and Park Ju-seok's (Hwayi: A Monster Boy) screenplay demanded. Yet, watching the film it is not difficult to come to the conclusion that the nameless extras playing the zombies are the real stars of this show. They are ferocious, scary, sometimes humorous, and the maliciously sudden way in which they turn into body-contorting, snarling beasties from benign, mundane salarymen, high schoolers, riot policemen and soldiers is highly effective. Special effects makeup artist Gwak Tae-yong (Thirst, A Werewolf Boy) and his crew, "body movement composer" Park Jae-in (The Wailing), who allegedly consulted the inhuman yet graceful movements of animated characters in such films as Ghost in the Shell 2: Innocence to come up with the choreography for the zombie's distinctive, jerky movements, and martial arts coordinator Heo Myung-haeng (New World) and his Seoul Action School staff collaborated with the DP Lee Hyung-deok (Sunny), Lighting Supervisor Park Jeong-woo (Venus Talk) and editor Yang Jin-mo (The Beauty Inside) to transform stuntmen and extras into such cunning creatures.

While careening at maximum speed and cleverly designed to generate much excitement and thrills among viewers, Train to Busan still does not forget to satirize a bunch of sensitive local issues. The disastrous sinking of the Sewol ferry and its tragic loss of many teenage lives, the food-and-mouth disease epidemic of 2010 that forced farmers to exterminate more than one million pigs, the clumsy efforts of the Park Geun-hye government to control the contents of media reportage, and other pointed references to recent events and controversies pepper the film. Few of these references would mean much to viewers outside Korea, yet they add up to an extra layer of melancholy that suffuses the film, culminating in the poignant ending (a response of sorts to Memories of Murder's dark and despairing "tunnel" sequence?), asking us how can we distinguish murderous zombies from ordinary humans, when the basic level of social trust has evaporated. It is also telling that Yeon purposefully subverts a few cliches familiar from contemporary zombie horror, including the characterization that would have encouraged a class conflict-centered interpretation, only to conclude with "the poor rabble are no class revolutionaries after all"-type nihilism. Whether this choice suggests a "softening" of Yeon's taste, or merely a commercial calculation on his part so as not to turn off potential viewers, remains unclear.

Not quite reaching the mind-shattering level of ingenuity and hutzpah scaled by Na Hong-jin's The Wailing, Yeon Sang-ho's Train to Busan is nonetheless a superior horror film that satisfies one's usual genre-based expectations and then some. With The Wailing already out, Train to Busan now in play, and the equally promising Seoul Station to be released soon, South Korea is shaping up to be the country to beat for the most satisfying summer horror extravaganza for the year 2016. (Kyu Hyun Kim)

Barring some unexpected, miraculous development taking place near the end of 2016, John H. Lee's Operation Chromite will take the prize as the year's worst Korean film. It is not like there is an objective standard for measuring the quality of a motion picture, so I am reluctant to stake my claim that there is absolutely no other 2016 Korean film as terrible as this bloated war epic, but I can honestly claim that only this film dared to so blatantly flaunt its "badness."

As its Korean title indicates, the film is about the fateful September 1950 landing of U.N. forces under the command of General Douglas McArthur on the shores of Inchon behind the North Korean enemy lines, a maneuver said to have turned the tide of the Korean War against the invading Communist forces. The motion picture chooses to tell this story from the POV of the South Korean naval intelligence officers and the Korean Liaison Office agents. Most characters are fictional. The shoes of the main protagonist and antagonist are filled in by Jang Hak-soo (Lee Jeong-jae, Assassination), the leader of the SK naval intelligence unit, and by Rim Gye-jin (Lee Beom-soo, The City of Violence), his North Korean counterpart, respectively: all actions and dramatic conflicts in the movie revolve around the confrontation between these two men.

This choice in itself is hardly a matter of concern. War film is not a monolithic genre. It usually consists of a variety of sub-genres. It could tell an epic historical narrative in the manner of The Longest Day (1962), turn itself into a contemporary action film like The Dirty Dozen (1967), or settle down to be an espionage thriller, as was the case with Where Eagles Dare (1968). Within this spectrum, Operation Chromite seems to fall somewhere between The Dirty Dozen and Where Eagles Dare. And again, this choice could have easily resulted in a terrific picture. The backstories surrounding the successful landing of the U.N. forces have not yet been exhaustively dissected among the viewing public, many of them still veiled in secrecy. As a subject matter goes, it was good enough to provide fresh historical interest as well as a considerable range of creative freedom.

This choice in itself is hardly a matter of concern. War film is not a monolithic genre. It usually consists of a variety of sub-genres. It could tell an epic historical narrative in the manner of The Longest Day (1962), turn itself into a contemporary action film like The Dirty Dozen (1967), or settle down to be an espionage thriller, as was the case with Where Eagles Dare (1968). Within this spectrum, Operation Chromite seems to fall somewhere between The Dirty Dozen and Where Eagles Dare. And again, this choice could have easily resulted in a terrific picture. The backstories surrounding the successful landing of the U.N. forces have not yet been exhaustively dissected among the viewing public, many of them still veiled in secrecy. As a subject matter goes, it was good enough to provide fresh historical interest as well as a considerable range of creative freedom.

What went wrong, then? The biggest, most obvious problem is that Operation Chromite works way too hard to present itself as an anti-North Korea propaganda. Most of the time and energy that should have spent on refining the narrative, characters and action setups have instead gone into riling up the viewers and squeezing reluctant tears out of their eyeballs. Adding insult to injury, the film inflates the role of Douglas McArthur (Liam Neeson) in order to make sure the viewers understand the operation's "world-historical importance." Unfortunately, McArthur's presence is awkward, completely mismatched to the rest of the film.

Needless to say, Operation Chromite miserably fails in its objective. It is fatally devoid of the kind of coolly manipulative quality that any first-rate propaganda film would come equipped with. It gets all worked up by itself, shedding buckets of tears, leaving the audience dry in the dust. Frankly, I have little evidence to believe that the director, John H. Lee, who had already gone down this path before in 71 into the Fire (2010), knew anything or cared about modern Korean history. He seems to see his position strictly as a gun-for-hire, the worst kind of attitude for the filmmaker of a propaganda film to assume. How could not it have sunk to the bottom of the barrel?

The film is a total failure as "pure entertainment" as well, whatever one means by that term. Operation Chromite thrashes around screaming and hollering, not having figured out what kind of movie it is supposed to be until (and beyond) when the end credits roll. The part with McArthur has the tone of a stilted biopic, rendering the controversial military hero into a sort of one-liner-spewing automaton rather than a flesh-and-blood human being. Jang Hak-soo's adventures deliriously switches genres from an espionage thriller, an action blockbuster to a serious war film and back, but there is no flow, no context and no logic to any of these shenanigans, and everything is executed in a dreadfully mechanical, obligatory manner. None of these elements are capable of drawing the viewer's attention for a minute. I won't even go into the sufferings visited on Jin Se-yeon (White: The Cursed Melody) as the sole "young and pretty woman" caught among barking and running male actors. Finally, the movie simply lacks the type of meticulousness and attention to detail today's Korean viewers expect in an A-class war film: did the filmmakers ever think about how detail-sensitive the military hardware enthusiasts and war film aficionados are? They wasted even the opportunity to reach out to those who could have forgiven all this awfulness so as to gaze agog at the "authentic" military hardware in action.

There have been regimes and eras in human history that produced great propaganda films. Acknowledging this fact does not mean that we are obliged to accept the "greatness" of these regimes and eras. It goes without saying that Leni Riefenstahl's documentaries, whatever we may think of them as works of art, are insufficient reasons for us to defend the Nazi ideology that gave birth to them. Yet, this truism cannot serve as an excuse for the regime capable of making only crass and mediocre propaganda films. Those who can only make crass and mediocre propaganda are one-hundred percent crass and mediocre themselves, for the mediocre ones are by definition unable to overcome their own mediocrity. (Djuna, translated by Kyu Hyun Kim)

Seoul Station, South Korea: hidden beneath the glittering restaurants, gift shops and platforms to the train are a group of homeless vagrants, old and young. One of them, an old man, staggers around bleeding profusely from an ugly bite wound on the neck. A couple of bystanders express concern but no one helps him. By the time his frazzled homeless buddy has convinced the police to take a look at the dead or comatose old man, the latter has mysteriously vanished. Meanwhile, 19-year-old Hye-seon (Shim Eun-gyung, Queen of Walking) is about to be evicted from a seedy motel. Her dorky boyfriend Gi-woong (Lee Joon, The Piper)'s idea of a solution is to set up an internet connection for online johns who want paid sex with underage girls. Hye-seon is outraged, yet her online photo somehow manages to be discovered by her father Suk-kyu (Ryu Seung-ryong, The Admiral: Roaring Currents). Suk-kyu meets up with Gi-woong pretending to be a client and gives him a sound thrashing. Together, they try to locate Hye-seon, when all hell breaks loose, with fast-moving, ferocious zombies pour out of Seoul Station to munch on the hapless Seoulites.

Seoul Station, the third animated feature film from Yeon Sang-ho (The King of Pigs, The Fake), has been marketed as a prequel to the megahit Train to Busan, with Shim Eun-gyung also making a cameo appearance in the latter live-action film as a young woman who first infects the train crew with the deadly epidemic. However, in reality, the connection between these two films is rather tenuous: not only is the direct continuity in terms of plot never established, it is not even clear whether the events in them are taking place in the same universe.