2009

"Haeundae", "Thirst", "Mother", "Breathless"

The year 2009 opened in difficult circumstances, to say the least. With a global financial crisis exacerbating a two-year old crisis in the Korean film industry, expectations for the year were low. The situation was particularly tough for mid-sized, genre-based commercial films, which in the previous few years had lost money for more often than they had earned it.

In better shape were Korea's internationally-recognized directors, with both Park Chan-wook (Thirst) and Bong Joon Ho (Mother) lining up high profile spring releases. Hong Sangsoo also turned in a new film Like You Know It All, shot for a tiny fraction of his usual budget. All three films would be invited to various sections of Cannes.

Surprisingly, low budget independent films were also showing considerable life in the midst of the crisis. Daytime Drinking and Breathless, two debut films shot on tiny budgets, earned critical praise and an encouraging degree of commercial success. Most astounding, however, was the smashing success of the low budget documentary Old Partner, about an elderly farmer and his cow, which as of May 1 was the best grossing film of the year with close to 3 million tickets sold. (written on May. 5)

Reviewed below: Daytime Drinking (Feb 5) -- Marine Boy (Feb 5) -- The Naked Kitchen (Feb 5) -- Handphone (Feb 19) -- Private Eye (Apr 2) -- Breathless (Apr 10) -- Thirst (Apr 30) -- Like You Know It All (May 14) -- Castaway on the Moon (May 14) -- Mother (May 28) -- A Blood Pledge (Jun 18) -- Bandhobi (Jun 25) -- Chaw (Jul 15) -- Haeundae (Jul 22) -- Possessed (Aug 12) -- The Pot (Aug 20) -- Treeless Mountain (Aug 27) -- Let the Blue River Run (Oct 8) -- Paju (Oct 28) -- A Brand New Life (Oct 29) -- Lost in the Mountains (Nov 12) -- The Actresses (Dec 10) -- Woochi (Dec 23).

| Korean Films | Nationwide | Release | Revenue | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Haeundae | 11,397,749 | Jul 22 | 81.02bn |

| 2 | Take Off | 8,092,676 | Jul 29 | 57.57bn |

| 3 | Woochi | 6,100,532* | Dec 23 | 44.03bn |

| 4 | My Girlfriend is an Agent | 4,078,293 | Apr 22 | 26.38bn |

| 5 | Running Turtle | 3,052,459 | Jun 11 | 20.62bn |

| 6 | Mother | 3,003,785 | May 28 | 19.97bn |

| 7 | Old Partner | 2,952,579 | Jan 15 | 19.08bn |

| 8 | Good Morning President | 2,583,767 | Oct 22 | 18.56bn |

| 9 | Thirst | 2,223,429 | Apr 30 | 14.84bn |

| 10 | Closer to Heaven | 2,153,068 | Sep 24 | 15.58bn |

| All Films | Nationwide | Release | Revenue | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Avatar (US) | 13,351,368* | Dec 17 | 124.87bn |

| 2 | Haeundae (Korea) | 11,397,749 | Jul 22 | 81.02bn |

| 3 | Take Off (Korea) | 8,092,676 | Jul 29 | 57.57bn |

| 4 | Transformers: Revenge of the Fallen (US) | 7,437,602 | Jun 24 | 50.70bn |

| 5 | Woochi (Korea) | 6,100,532* | Dec 23 | 44.03bn |

| 6 | 2012 (US) | 5,431,440* | Nov 12 | 38.89bn |

| 7 | Terminator Salvation (US) | 4,527,614 | May 21 | 29.69bn |

| 8 | My Girlfriend is an Agent (Korea) | 4,078,293 | Apr 22 | 26.38bn |

| 9 | Running Turtle (Korea) | 3,052,459 | Jun 11 | 20.62bn |

| 10 | Mother (Korea) | 3,003,785 | May 28 | 19.97bn |

* Includes tickets sold in 2010. Source: Korean Film Council.

Seoul population: 10.2 million

Nationwide population: 49.8 million

Market share: Korean 48.8%, Imports 51.2% (nationwide)

Films released: Korean 118, Imported 243

Total admissions: 157.0 million

Number of screens: 2055

Exchange rate (2009): 1279 won/US dollar

Average ticket price: 6970 won

Exports to other countries: US$14,122,143 (Japan: 42%)

Average budget: 2.3bn won including 0.8bn p&a spend

Hyuk-jin (Song Sam-dong), a recent returnee from the military service, is a shy and soft-spoken twenty-something guy. During a drunken mash-up with his buddies, his best friend Ki-sang (Yook Sang-yup: are these actors' names for real?) invites him to stay at his relative's guest house (called "pension" in Korea) in the remote resort town of Jeongseon, Kangwon Province. Next day, Hyuk-jin arrives at Jeongseon only to find himself stranded without his friends. He reluctantly spends the night in the town, in a wrong guest house, as it turns out. To add insult to injury, his awkward attempt to "pick up" the next-door neighbor (Kim Kang-hee) results in an ego-damaging brush-off by her thuggish companion (Tak Seong-joon). But Hyuk-jin's troubles are far from over, as the weird locals he encounters, including a motor-mouthed woman with nasty temper (Lee Ran-hee) and a good-natured truck driver (Sin Woon-seop), begin to pose threat not only to his financial security and mental stability but perhaps to his chastity (?).

Filmed extremely cheaply (with the total budget allegedly under 10 million won) over a couple of years by director Noh Young-seok with zero film-school background, Daytime Drinking won an audience award at the 2009 Jeonju Film Festival and landed a robust distribution deal, even though its box office performance did not measure up to the mind-boggling success of Old Partner, another extreme low-budget indie feature.

Filmed extremely cheaply (with the total budget allegedly under 10 million won) over a couple of years by director Noh Young-seok with zero film-school background, Daytime Drinking won an audience award at the 2009 Jeonju Film Festival and landed a robust distribution deal, even though its box office performance did not measure up to the mind-boggling success of Old Partner, another extreme low-budget indie feature.

Daytime Drinking is definitely not a good showcase of filmmaking skills on the part of director Noh: in some aspects it's downright amateurish. For instance, the camera seems to have trouble keeping a proper focus in some distant shots, resulting in blurred edges, as if we are seeing them through an opaque window. What's funny is that these scenes, usually showing Hyun-sik stranded in the middle of nowhere, make him, in the context of this rough-and-tumble but strangely charming flick, appear sunk in the middle of a fish bowl, amusingly illustrating the character's exasperation and, shall we say, dork-ish qualities. The film is full of these even-its-goofs-are-hilarious moments.

Outwardly Daytime Drinking could be mistaken for a low-octane parody of a Hong Sangsoo film (the main characters swig hard liquor like whales in both cases: well, this one is called Daytime Drinking after all, and no, we are not talking about afternoon tea here), but it's far loosely structured and plainly mounted, and its ultimately good-natured, deadpan humor is pretty unique, at least among Korean movies. Song Sam-dong as Hyuk-jin, even though barely "acting" in the technical sense, serves as the perfect foil for the languorously surreal characters he runs into. Even when the troubles keep piling up, the doofus kid always stays one-and-a-half steps behind the right response, making his expression of slow-burn befuddlement, when done right, both droll and sympathetic.

The film only loses its bearing in the last thirty minutes or so, when Hyuk-jin finally meets up with Ki-sang and visits the "right" "pension." This section features an embarrassingly inane "nightmare sequence," which probably could not have been done properly with the meager resources available to the crew, and the explanation of Ki-sang's real motivation that pivots on a disappointingly lazy storytelling device. I wish the movie had a more dynamic, emotionally cathartic resolution that shows Hyuk-jin actively taking some initiatives against his tormentors. (I guess he does a tiny bit of that, off-screen)

Daytime Drinking may not be an earth-shaking masterpiece, but Noh Young-seok's no-budget comedy has its heart in the right place, and richly deserves the praise it has garnered from the viewers.

A note: Be careful not to be ambushed by the film's end-credit music, also composed by director Noh a la John Carpenter. It's a sort of techno-ppongjjak, like ballroom muzak played for International Conference of the Organ Grinder's Monkey Association: I warn you, you won't be able to get it out of your brain once you heard it. (Kyu Hyun Kim)

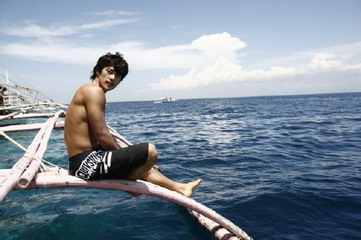

Cheon-soo (Kim Kang-woo, Rainbow Eyes) is a talented swimmer, once a competitor in international games. A bad gambling habit, however, ruins him financially. He gets willy-nilly recruited into a dope courier job for the gangster President Kang (Jo Jae-hyun, Hanbando, Romance). The task seems to involve swimming past the Korea-Japan border with a string of bags filled with dope inside your intestines (As I had suspected it would, the movie milks this set-up for ca-ca jokes, so sensitive viewers beware). Kang is obsessed with his former colleague's daughter, a fruit tart named Yuri (Park Si-yeon, Dazimawa Lee), and naturally she and Cheon-soo fall in love with each other, after sharing several cosmetics-commercial moments of cocky stares and pouty insults. Just to make things more complicated than necessary, Cheon-soo is being tailed by a corrupt cop named "Dog Snout (Lee Won-jong, The Foul King, Hi Dharma!)," who has a past history with President Kang.

Marine Boy is a typical commercial "action film" being turned out with a sense of foot-dragging futility by the Korean industry these days. It takes a premise and a plot vaguely reminiscent of a '70s or '80s Hollywood action thriller (this time, it's Peter Benchley's The Deep, itself more than a little schlocky and illogical) and tries to update them with slick visuals imported from TV commercials, while "Koreanizing" the characters by burdening them with arch-melodramatic gestures, dialogues and motivations. Jo Jae-hyun and Lee Won-jong, both terrific actors, try gamely to bring some verve and finesse to their roles that seem to be defined more by their Kyongsang Province accents than anything else. Director Yun Jong-seok, like many Korean debut directors, is competent if not inspired, and knows how to wrangle camera angle and editing to keep the pace up. Unfortunately, the ridiculously convoluted plot and motivations quickly drag down the proceedings. Park Si-yeon, foxily charming in Dazimawa Lee, here has to grapple with a role that cannot decide if Yuri is just a spoiled brat with a drug problem or a manipulative femme fatale. And wasn't she supposed to be a serious addict? Or maybe that was a put-on, too, since we never see her once without looking like she just stepped out of a Vogue photo spread. I suppose since she and Cheon-soo got to sip Pina Colada at Palua in the end, we shouldn't be asking these niggardly questions. As for Kim Kang-woo, I still like his wild-cat hauteur with a dash of vulnerability, but he really should fire his agent or just stay away from whoever it is that advises him on choosing scripts.

Marine Boy is a typical commercial "action film" being turned out with a sense of foot-dragging futility by the Korean industry these days. It takes a premise and a plot vaguely reminiscent of a '70s or '80s Hollywood action thriller (this time, it's Peter Benchley's The Deep, itself more than a little schlocky and illogical) and tries to update them with slick visuals imported from TV commercials, while "Koreanizing" the characters by burdening them with arch-melodramatic gestures, dialogues and motivations. Jo Jae-hyun and Lee Won-jong, both terrific actors, try gamely to bring some verve and finesse to their roles that seem to be defined more by their Kyongsang Province accents than anything else. Director Yun Jong-seok, like many Korean debut directors, is competent if not inspired, and knows how to wrangle camera angle and editing to keep the pace up. Unfortunately, the ridiculously convoluted plot and motivations quickly drag down the proceedings. Park Si-yeon, foxily charming in Dazimawa Lee, here has to grapple with a role that cannot decide if Yuri is just a spoiled brat with a drug problem or a manipulative femme fatale. And wasn't she supposed to be a serious addict? Or maybe that was a put-on, too, since we never see her once without looking like she just stepped out of a Vogue photo spread. I suppose since she and Cheon-soo got to sip Pina Colada at Palua in the end, we shouldn't be asking these niggardly questions. As for Kim Kang-woo, I still like his wild-cat hauteur with a dash of vulnerability, but he really should fire his agent or just stay away from whoever it is that advises him on choosing scripts.

I think I would have been more charitable to Marine Boy if it, like The Deep, at least had a good sense to regale us with beautiful underwater footage. But no, the movie wastes most of its running time among boring characters jawing unconvincing one-liners and "tough guy talks," ensconced in chi-chi apartment living rooms, or seated in fancy cars barking into cell phones. Where is "marine" in Marine Boy? Frankly, who gives a sardine's fin if President Kang is in love with Yuri? Was that the point of this alleged "action film?" Marine Boy was at one point the most frequently downloaded Korean film of this year: an "oceanic action film" fit to watch on a 17-inch PC screen? I somehow doubt that's what this movie's crew and cast had in mind while making it. (Kyu Hyun Kim)

The day of Ahn Mo-rae and Han Sang-in's wedding anniversary is pretty eventful. First, Mo-rae (Shin Min-a, Go Go 70) cooks breakfast,serving it on their best china, hoping to get Sang-in (Kim Tae-woo, Woman on the Beach) into the mood for love before he goes to work. (It works.) Second, Sang-in quits his high-end stockbroker job so that he can devote himself to his lifelong dream of running a fancy restaurant. Third, while shopping for an anniversary gift for Sang-in, Mo-rae sneaks into a closed gallery, where she encounters another illicit visitor -- a very handsome young man with whom she hides when the gallery owner turns up. Mo-rae, overcome by heat and dizziness, has a sudden sexual encounter with the stranger, who then vanishes. Fourth, Sang-in tells Mo-rae over dinner that he's expecting a mentor to help him plan the menu for his dream restaurant: a brilliant young French-Korean chef who will arrive that evening. Fifth, you guessed it: Park Du-re (Ju Ji-Hoon, Antique, Princess Hours), the French-Korean mentor, turns out to be Mo-rae's zipless stranger, who now will be staying with the young couple, sleeping in the room that had belonged to Sang-in's late mother.

From there the story goes about as you would expect. Mo-rae is powerfully drawn to the seductive Du-re while Sang-in gets cooking lessons from him. Eventually everything comes crashing down, but Kitchen is a comedy, so it turns out all right in the end. (The official English title of this movie is The Naked Kitchen, but it's a cheap tease, since nobody gets naked, even metaphorically. This is a very buttoned-up movie. The Korean title is nothing but the English word Kitchen, so that's what I'll call it here.)

From there the story goes about as you would expect. Mo-rae is powerfully drawn to the seductive Du-re while Sang-in gets cooking lessons from him. Eventually everything comes crashing down, but Kitchen is a comedy, so it turns out all right in the end. (The official English title of this movie is The Naked Kitchen, but it's a cheap tease, since nobody gets naked, even metaphorically. This is a very buttoned-up movie. The Korean title is nothing but the English word Kitchen, so that's what I'll call it here.)

Kitchen didn't do well at all, which is surprising since it features three bankable stars. It wasn't even noticed as a coming release here at Koreanfilm.org. I wouldn't have known about it if it hadn't been featured in a book-length survey of Korean movies for 2008, which gave some idea of its visual appeal and emotional dynamics, so I picked up the DVD. First-time director Hong Ji-young made a very pretty movie, her cast turned in fine performances. So what is wrong?

If not for the fact that not many other people liked it either, I'd guess my lack of enthusiasm for Kitchen was just my personal hangup. First, I suspect someone loved Jean-Pierre Jeunet's 2001 hit Amelie, a movie I hated for the way it reveled in its own cuteness - so if you liked Amelie, maybe you should give Kitchen a try. Shin Min-a seems to be channeling Audrey Toutou, and has been made up and coiffed to recall her perky obnoxiousness. The soundtrack slathers on a Parisian-style waltz, Sang-in's restaurant will feature a Korean-French fusion cuisine, and of course Du-re is a French-Korean adoptee. The food is a major character in the movie, with lots of close-ups of yummy-looking table spreads.

Under all the Francophile syrup there are interesting characters. Mo-rae and Sang-in have been friends since childhood. He didn't mind that she followed him around, calling him hyung or Big Brother (though Korean girls are supposed to call their older brothers oppa), and their marital relationship is an odd but appealing mix of hot sex and best buddies. The script explores this intelligently, as when Mo-rae tells Du-re, "To me, love doesn't mean much. It's Han Sang-in. Not because I don't love someone, or love more someone else. I'm just trying to be me."

Kitchen also flirts, ever so delicately, with male homoeroticism. There's a hint that Sang-in and Du-re had an affair when they met in France; when Sang-in shows Du-re his room, Du-re asks him to spend the night with him. Sang-in begs off awkwardly: "Well... I have a wife." But Kitchen doesn't explore these possibilities; it refers to them glancingly, trying to make itself look spicier than it really is. It always draws back to the pretty surface. In this it suffers by comparison with the far superior Wanee and Junah (Kim Yong-gyoon, 2001), which shares some of its topics: a relationship more of friendship than of passion, flirting with bisexuality and gender games. Kitchen just frustrates me, though; because it falls so far short of what it might have been. The film seems torn between taking chances and playing it safe, and playing it safe didn't help either artistically or at the box office. (Duncan Mitchel)

A warning: if you are looking for a feel-good escapist entertainment, avoid Handphone. That type of film must meet several conditions. First and foremost, we should be able to feel for its protagonist. Conversely, the piece's villain should brook no sympathy. The violence the good guy employs against the villain must be clean-cut, not messy like one we see in real life. And so on.

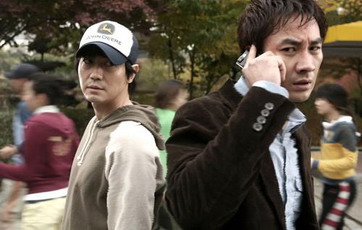

Handphone ignores these conditions. In fact, it gleefully violates them. Seung-min the entertainment agent, the film's alleged hero, is not someone we would voluntarily feel any sympathy toward. He is shallow, low-rent and lacking in conscience. Yi-gyu, who accidentally picks up Seung-min's cell phone and decides to blackmail him, is, on the other hand, someone easier for us to root for. Yi-gyu is slowly crumbling under the pressure of working life, unlike Seung-min, whose shallow character seems to actually enhance his ability to navigate through the treacherous waters of his profession. The film is aware of this contrast, and puts Yi-gyu through a wringer to prove its point. Naturally, the violence eventually sparked between these two disturbed characters does not help the viewers whatsoever in reducing the latter's stress.

Handphone ignores these conditions. In fact, it gleefully violates them. Seung-min the entertainment agent, the film's alleged hero, is not someone we would voluntarily feel any sympathy toward. He is shallow, low-rent and lacking in conscience. Yi-gyu, who accidentally picks up Seung-min's cell phone and decides to blackmail him, is, on the other hand, someone easier for us to root for. Yi-gyu is slowly crumbling under the pressure of working life, unlike Seung-min, whose shallow character seems to actually enhance his ability to navigate through the treacherous waters of his profession. The film is aware of this contrast, and puts Yi-gyu through a wringer to prove its point. Naturally, the violence eventually sparked between these two disturbed characters does not help the viewers whatsoever in reducing the latter's stress.

Well, what can I say? Handphone is masochistic, cynical and ultimately misanthropic. Few characters in this film are mentally stable or morally upright. Most of them are seriously flawed in one way or another: a few are annoying on a metaphysical scale. Of course, since Handphone's hateful depiction of humanity is based on the relational dynamics of the Korean society as well as the stereotypes of its members, we might accept that the scope of its misanthropy is limited to those whom we see around us. Whatever the director originally intended with all this is rather beside the point.

How does Handphone stack up as a thriller? Its structure is rather loose. The cell phone in question can only do so much as a multi-purpose McGuffin. The filmmakers eventually resort to improbable coincidences and a bit of cheating. As in his previous film Paradise Murders, director Kim Han-min does not quite know when to end the movie. A double-entendre epilogue is frankly redundant, although we could concede that this looseness does contribute to extending the agony of the climax.

The film's biggest assets, not surprisingly, are its two stars: Uhm Tae-woong and Park Yong-woo. They are quite well cast for the respective roles of a sleazy agent and an "emotional laborer" rotting from the inside, producing a powerful synergistic effect. If I were compelled to compare the two, I must say Park seems to benefit slightly from a more three-dimensional character he is playing.

Let me finish by observing that Handphone performs an excellent public service by providing those of us living in the contemporary Korean society with three useful and important lessons: 1) Let's keep a watchful eye on any digital device that contains private information: 2) Let's pay attention to the mental health of the emotional laborers, lest they snap: 3) And most importantly, let's not be aggressively rude to total strangers. The payoff can be really ugly. (Djuna, translated by Kyu Hyun Kim)

I'd heard some positive things about Private Eye before actually catching the movie in the theater. A detective story set in the early 20th century under the Japanese colonial rule! With Hwang Jeong-min, Ryu Deok-hwan, Uhm Ji-won, Oh Dal-soo in the cast! And the screenplay picked up some kind of award! Well, the last bit was not so intriguing. It's not uncommon for an acclaimed screenplay to turn out to be disappointing. Still, the first two pieces of information were enough to get my expectations up.

The details of the story go like this. Hong Jin-ho, the character played by Hwang Jeong-min in this film, is a pro at things like tracking down missing people and exposing illicit love affairs. He doesn't call himself a private eye, but that's basically what he is. He usually tries to avoid tight situations but is one day pushed into a rather sticky murder case, when Jang Gwang-soo, a med student who collects abandoned bodies for dissection, asks Hong to find the murderer of his latest cadaver.

The details of the story go like this. Hong Jin-ho, the character played by Hwang Jeong-min in this film, is a pro at things like tracking down missing people and exposing illicit love affairs. He doesn't call himself a private eye, but that's basically what he is. He usually tries to avoid tight situations but is one day pushed into a rather sticky murder case, when Jang Gwang-soo, a med student who collects abandoned bodies for dissection, asks Hong to find the murderer of his latest cadaver.

Wait. I mean, wouldn't it be obvious to a med school student that if you find a body with a knife wound in it, it was probably a victim of murder? The film begins to lose its footing this early on. The story wouldn't make sense even from the viewpoint of early 20th-century Seoulites. Any moderate reader among them would have been familiar with the ABCs of detective novels. This would have included a cadaver-hungry medical student, by the way. It could be that Jang was simply thinking that his actions were fine if the body belonged to some insignificant fellow, but less so if it turned out to be the son of a high-ranking official that spells out mortal danger for him-- but then the audience wouldn't be able to like him as much.

If it's all an excuse to bring together a private eye and a doctor-to-be as a murder investigation team, well, I can't say I don't understand. The folks who made this film were indeed aiming for a Holmes and Watson partnership, colonial Seoul-style. The names match somewhat, with a little stretch: Holmes - Hong Jin-ho, John Watson - Jang Gwang-soo, see? But there's a fatal flaw here. As you Baker Street Regulars already know, Holmes and Watson are highly distinctive characters. Just a few pages into the story and you know what kind of people they are. In Private Eye, it's much harder to figure out the two main characters. Especially Hong Jin-ho. What is he, anyway? A man of "the little gray cells" like Hercule Poirot? No, he's too dumb for that. Or an eclectic super-hero like his namesake Holmes? He doesn't have half the skills. Maybe a tough guy like Sam Spade? Not so. Hong can't hold up in a fistfight, nor does he have the guts to handle the life underground. Then why in the world is this man the hero?

Hong's plight springs from the fact that the film denies him a chance to reveal his unique features or skills. In other words, the screenplay was not very well thought out. The film doesn't have much mystery in it. There's no foreshadowing that lasts more than ten minutes, and most clues are explained away in the very next sequence. On top of that, there's just one suspect. Or were there two? In any case, there's no room for a detective to do anything, much less show himself off. Even that snazzy toy that looks like something Q might make for 007 is simply no good if the man doesn't get to use it.

And who makes these toys for Hong? It's the inventor Soon-duk, played by Uhm Ji-won. Soon-duk, although not very realistic, could have been an interesting character: a lady of noble birth that gets hooked on modern Western science and sets up a lab in an abandoned church to cook up all sorts of inventions. A personage of these dimensions might well be the heroine in a sensible screenplay, but here she remains underdeveloped and misused in a supporting role.

Another badly formulated character is the police officer Oh Young-dal. As always, Oh Dal-soo turns in a fun, top-notch comic performance, but his character really does not deserve such cutesy treatment. It's always a bad idea to put together in one character the roles of a harmless clown and an accomplice in crime. No amount of good acting on Oh Dal-soo's part can pull it off, however excellent an actor he may be.

The film attempts to cover up gaping holes in the story and characters with action scenes, but those aren't so well-crafted either. The chase scene between Hong and a mysterious pursuer is a glaring example. The city-stomping stunts on the fabulous open sets could have been "cool," or so the makers must have thought, but it did not work. The rhythm is awkward and the timing a mess. The entire sequence here is meant to end on a clear slapstick note, which might have looked good in the script. But where one second would have been enough, the film drags on for a few more seconds and the result is a boring scene. This is just one of many such unwise decisions. All in all, I don't believe that the makers of Private Eye are giving film as a medium its full workout. (Djuna, translated by ye-jung)

Sanghoon, the character played by Yang Ik-June in Breathless, communicates mostly in cusswords, beats up people for a living, and thinks he's got a God-given right to spit all over the place. Your everyday guy -- just with all of the worst qualities one can get through the combination of unlucky breeding and bad genes.

Sanghoon works as a thug for a company. His job is to beat up and threaten weaker folks. It fits him like a glove. Maybe it is better for guys like him to stay there, instead of messing with other parts of society -- although his victims probably would not agree.

Sanghoon works as a thug for a company. His job is to beat up and threaten weaker folks. It fits him like a glove. Maybe it is better for guys like him to stay there, instead of messing with other parts of society -- although his victims probably would not agree.

Sanghoon is far from having a knack with people, but for some reason he's got some complex relationships going on around him, which add flavor to the movie. His father, for one, is stuck at Sanghoon's house after being released from jail. There is also his recently divorced stepsister and her son. One day he has a nasty run-in with a neighbor, a high school girl called Yeonhee, and due to Yeonhee's odd taste in men (or perhaps a desperate ploy to incorporate at least one decent character into the film) the two build up something like a friendship. Yeonhee is burdened with a total jerk of a brother and a disturbed Vietnam veteran for a father. The cast also includes Sanghoon's friend-slash-boss Mansik and his cronies at work.

These folks have one serious problem in common: their fathers. All of the father figures in this film are downright horrible people. They assert their existence only through displays of violence. They do awful things that come back to haunt them later. Of course, it's not entirely their fault. Yeonhee's father, for example, is the victim of some kind of illness. But somehow I don't think he would have been much of a pleasant person even if he had not been sick. The film portrays a disease that spreads violence and ill humor, and fathers are the carriers of the virus.

From this sprouts the main dilemma of the film. The cure for this 'disease' is to cut away one's life from the father, then run like hell. The few close-to-normal characters in the film, like Sanghoon's stepsister or Mansik, have either succeeded in pulling away from the violent father figure or are fatherless from the start. In Sanghoon and Yeonhee's case, though, it does not work out that way. Circumstances and blood-ties keep them tangled up with their fathers for life. Since they cannot get away, the film repeatedly attempts to reconcile them with the fathers somehow, showing symptoms of a whiny and unimpressive sort of self-vindication. Sanghoon, in particular, has already sunk pretty low, maybe as low as the father he hates so much, so he must take drastic measures to avoid serving as an excuse for the kind of man his father is, and one that he is becoming. This is not so easy. What the film shows us is probably the best he could have done under the circumstances.

Breathless is a rough and unpolished film, made extremely low-budget under the hands of an inexperienced director. However, being rough and unpolished does not equal lack of professionalism. True, 130 minutes is on the drawn-out side, and too many close-ups clog up the screen. On the other hand, Yang Ik-joon's direction of his cast is close to perfect, and the lines jump straight out of real life. The plot could be more creative, but it is logical enough. The style goes well with the story, the pace is appropriate, and the music is well-designed. In other words, for all his talk about not knowing what he's doing, Yang has turned out a better-made film than most films being churned out in the Korean movie scene today. Whether he can keep up the raw energy driving this honest-to-goodness portrayal of lives gone sour throughout his future career remains to be seen. With Breathless, he is just beginning to pour out the words that must have been fermenting inside him all his life. (Djuna, translated by ye-jung)

Sang-hyun (Song Kang-ho), a tormented priest, volunteers as a human guinea pig at an African research facility, working on the vaccine for a virulent virus called EV (which only infects celibate or sexually inactive men). The virus kills him, but he is miraculously resurrected by blood transfusion. Unfortunately, the miracle comes with a serious side effect: he turns into a vampire. Only continuous supply of fresh human blood can reverse the symptoms of EV infection. While grappling with his disturbing new habit-and superpowers-Sang-hyun becomes attracted to Tae-ju (Kim Ok-vin, Dasepo Naughty Girls ), unhappily married to his childhood friend Kang-woo (Sin Ha-gyun, Sympathy for Mr. Vengeance), a bizarrely infantile hypochondriac living under the thumb of his manic dressmaker mother Ms. Ra (Kim Hae-sook, Open City).

Thirst, which, along with Bong Joon Ho's Mother, is 2009's most anticipated Korean film, opened to good if not spectacular box office performance (0.8 million tickets sold in the first weekend for the Seoul theaters). Unlike Park Chan-wook's "revenge" trilogy, however, the movie is generating extreme reactions from both viewers and critics. Some reviews have blasted it as a pretentious bore or a poorly conceived adaptation of Emile Zola's Therese Raquin (from which this film borrows certain plot points and a love triangle central to the plot): only a few critics have hailed it as a masterpiece. Among the viewers, the chasm is even wider: internet comments freely range from "a piece of trash" to "the best movie I have seen in 10 years."

Thirst, which, along with Bong Joon Ho's Mother, is 2009's most anticipated Korean film, opened to good if not spectacular box office performance (0.8 million tickets sold in the first weekend for the Seoul theaters). Unlike Park Chan-wook's "revenge" trilogy, however, the movie is generating extreme reactions from both viewers and critics. Some reviews have blasted it as a pretentious bore or a poorly conceived adaptation of Emile Zola's Therese Raquin (from which this film borrows certain plot points and a love triangle central to the plot): only a few critics have hailed it as a masterpiece. Among the viewers, the chasm is even wider: internet comments freely range from "a piece of trash" to "the best movie I have seen in 10 years."

Even for someone like me, a rabid-crazy Park Chan-wook fan, the initial reaction to Thirst was that of deep unease: I literally could not name what it was that I was feeling as the end credits rolled up. All I knew for sure was that I had to see it again immediately. Only after the second viewing did I understand that the unease came from my inertial inability to acknowledge that I'd just watched a bewildering but awesome work of art, well-nigh indescribable in its insane, alchemic melding of disparate genre elements.

Thematically, Thirst is as a straightforward and relentless exploration of Catholic guilt as any Euro-American film I have ever seen--as painful as Abel Ferrara's Bad Lieutenant, as scorching as Bunuel's Viridiana-- with its profoundly contradictory attitude toward the glamour and agony of desire. The protagonist Sang-hyun, like Graham Greene's Scobie in The Heart of the Matter, is tragically, sympathetically flawed. He has enough dedication to face certain death in the service of humanity yet cannot stop his pity toward a beautiful, unhappy young woman growing into passionate love. He is powerless to stop the faithful who regard his vampirism as a sign of being touched by God: having committed a mortal sin out of love, he figuratively and literally drowns in guilt.

Song Kang-ho gives yet another brilliant performance (I don't think he can just walk through a role even if his life depended on it), but it is not a flashy one: as was in Secret Sunshine, it's a catcher's turn that perfectly anchors the emotional content of a particular scene and at the same time generously puts the spotlight on other actors. I can only hope that Euro-American critics are not lazy (or foolish) enough to mistake the essential passivity of Sang-hyun's character for the lack of talent on Song's part.

A lot of media attention has been paid to the explicit sex scenes between Song and Kim Ok-vin, an interesting choice on Park's part. He seems to have had a young Isabelle Adjani (The Story of Adel H was allegedly one of the films Park recommended to Kim as a research material) in mind: fiery, heartbreaking, maybe a bit raw. Kim is stunningly sexy and gorgeous in both wilted-housewife and full-blown femme fatale modes, and throws all of herself into the role, but I cannot help but seeing Yeom Jeong-ah (who appeared as a fictional vampire in Park's "The Cut" from Three Extreme) or Lee Young-ae as Tae-ju. Kim strikes me as a bit too young and contemporary: she does not strike as someone who could have tolerated long years of indentured servitude in exchange for meager domestic comfort. She is blindingly beautiful, I must admit, in a blue hanbok dress.

The rest of the cast is equally superb: Oh Dal-soo, Sin Ha-gyun, Kim Hae-su, Kim Jee-woon regulars Park In-hwan (The Quiet Family), as a blind senior priest with a wry sense of humor, and Song Young-chang (the head-rocking section chief from Foul King), as a hard-nosed former cop. Their ensemble acting in the sequence where a character tries desperately to alert the presence of a vampire to other unsuspecting guests is a piece de resistance, superior to any similar scene in Sympathy for Lady Vengeance.

By now we expect not just high quality jobs but extraordinary aesthetic achievements from Park Chan-wook's regular staff, and Thirst certainly does not disappoint. Production designer Ryu Seong-hee is responsible for the uncommonly reined-in colors-bleached white and faded green-of the religious and medical institutions as well as ever-so-slightly off-kilter hues of Ms. Ra's domain-deranged blues and slick browns. Lenser Jeong Jeong-hoon weaves pure magic with shadows and light, culminating in the stunning vista of the ocean spreading in scarlet red, illuminated by the setting sun, as looked on by the eyes of the doomed protagonist.

Oh, is it a good vampire film, you ask? It sure as heck is- the tomato juice flows abundantly in horrendous, cringe-inducing scenes of violent exsanguinations, and there are many insanely creative twists on the familiar genre staples that will either stun you into silence or make you gape in disbelief. Have you wondered how a vampire can convince a blind person that he is one? Watch Thirst. Have you ever wondered whether becoming an immortal creature will heal calluses on the soles of your foot? Again, watch the movie. There are at least two sequences in this film that matches in sheer audacity and jaw-dropping hutzpah the notorious "long-take corridor action" set piece in Oldboy.

But Thirst is not an exhilarating showcase of directorial vision and filmmaking pizzazz that Oldboy was. Despite occasional insertions of absurdist deadpan humor, it is at its basis a tragic romance. And despite much bloodletting, the film is not interested in generating frisson of fear, but a deep sense of melancholy. In the end it returns, perhaps in a purer form than ever, to Park Chan-wook's starting point: the torturous reflection on the impossibility of salvation, the moral weight of sin and desire, and the agonizing scream of a man against God who may or may not exist, and may or may not love him. If Thirst were a book, it probably deserves a whole shelf of its own: regardless of one's likes or dislikes, it is a true work of art that calls out for the defense of its artistic honor by those who are taken with it, way beyond the question of one's taste in specific genres or stylistic choices. (Kyu Hyun Kim)

"The two biggest self-deceptions of all are that life has 'meaning' and that each of us is unique. One can see that evolving a built-in obscuring mechanism for those depressing and inevitable insights might be of practical use." - Talking Heads frontman David Byrne in Bicycle Diaries (p 74).

In spite of the variations spun on recurring themes in the oeuvre of director Hong Sangsoo, when you repeat so many themes, bits of dialogue, actions, gestures, and characters (his films are dominated by traveling role-players in the film community and writers and visual artists), you can't help but leave viewers with a sense of meaninglessness to the films and the dialogues and the characters. Even though we do repeat ourselves often in real life, watching the repetition of sections of dialogue in Hong's films strips them of their meaning, echoing their in-authenticity. However true it might be when our main character Director Ku Kyung-nam repeats his motivation for being on the film jury panel of the Jecheon Film Festival to an ambitious, over-eager actress and her enabling stage-mom that "Many good films get buried unfairly", the sincerity is brought into question when the actress responds "Like your films?" He takes offense to this because his words didn't have the effect he'd hoped, or better yet, his own words were used against him, resulting in an awkward moment that is one of the many Hongian beats spread out throughout Like You Know It All to the delight of Hong fans sprinkled everywhere.

Not just characters are repeated, but the very actors who play them. And Like You Know It All, Hong's ninth film, repeats actors like no other. Three Hong alumni pepper this film. Kim Tae-woo of Woman Is the Future of Man and Woman on the Beach is our film director Ku Kyung-nam; Uhm Ji-won returns from Tale of Cinema to be out first female, Gong Hyun-hee playing the festival director of the Jecheon Film Festival; and Ko Hyun-jung finds herself on a beach again after Woman on the Beach as the second female, Ko Sun, the May wife of a December husband who happens to be a revered senior artist of Jeju Island.

Not just characters are repeated, but the very actors who play them. And Like You Know It All, Hong's ninth film, repeats actors like no other. Three Hong alumni pepper this film. Kim Tae-woo of Woman Is the Future of Man and Woman on the Beach is our film director Ku Kyung-nam; Uhm Ji-won returns from Tale of Cinema to be out first female, Gong Hyun-hee playing the festival director of the Jecheon Film Festival; and Ko Hyun-jung finds herself on a beach again after Woman on the Beach as the second female, Ko Sun, the May wife of a December husband who happens to be a revered senior artist of Jeju Island.

This film can be separated into two blocks like many of Hong's other films. We begin at the bus stop where Ku (the subtitles reference last names, so I'll follow that pattern) is picked up at a bus stop to be a part of a jury at the Jecheon Film Festival. We begin again at the second section where Ku is picked up at the airport by an old friend who now works for the Jeju Film Commission and teaches film at the local university, which is why Ku is there, to give a lecture and pick up a stipend for the effort. Both times he is picked up, the welcoming person was delayed because they had to pick up bread. The repetitions begin early, and don't stop.

And these Like You Know It All repetitions seep into the Hong films that preceded it. In the Korean Film Council Korean Directors Series volume devoted to Hong, American film theorist and writer David Bordwell notes "Hong has remarked that he is less interested in a dramatic structure than a pattern, and his narrow repertoire of situations allows us to perceive echoes and variations among the actions. This geometric model of storytelling has pushed him beyond his contemporaries' looser, more anecdotal and additive narrative strategies" (p 24). In Like You Know It All, Hong continues the arm-wrestling, extending back to the film before, Night and Day. Ku sees a frog in the swimming pool like the insect in the planter of The Day a Pig Fell In the Well or the random dog in The Power of Kangwon Province. Ku will find himself wounded literally in accordance with Hong's metaphorically wounded males, just like in Hong's other films. Hong even covers up the cause of the wound on Ku's cheek with a reference to an actual scene that happened in Turnging Gate, claiming a few thugs beat him up because "One of them said I was looking at their girl's legs." In Turning Gate our male tries to cover up that he was looking at a woman's legs by saying he was looking at a poster above the woman. Here Ku covers up the bizarre reaction of a former friend with what was covered up in a film before.

It is this repetition that keeps Hong's films from being unique, yet making Hong's oeuvre unique at the same time. They are one long treatise on the inability to be authentic, to be sincere. It is a treatise on the inherent meaninglessness of our words and actions, and by extension, the meaninglessness of cinematic signifiers, such as his refusal to announce his character's dreams. As Korean film critic Huh Mooning (the editor of the previously mentioned KOFIC book on Hong) argues, "In Hong Sangsoo's films, meaninglessness is more strongly experienced than meaning. His film is a 'form of meaninglessness'" (p 10). Even more so, ' . . . his films have questioned the nature of movies and redefined it" (p x). The supreme irony of Hong Sangsoo's films is that he takes an artistic medium that the very patrons of which find so meaningful and shows that audience the inherent meaninglessness in the medium. And the further irony is this is what makes his work so meaningful to the small group of us who follow and anxiously anticipate his films.

As Bordwell also points out, Hong's films are memory-tests. His films require re-watching because you want to go back to previous scenes to check if you recall correctly. His scenes are like the cards you flip in a game of memory. And by repeating dialogue and actions and themes throughout his films, you are enticed to not only re-watch a single film, but to re-watch past Hong films. His films are perfect for DVD technology since his films are their own DVD extras in that they propel you to click back to previous scenes, and previous scenes in previous films.

Interestingly, Hong Sangsoo's memory-testing oeuvre arose at the very moment when our memories have been augmented by the technologies available to those of us who can afford them. As Viktor Mayer-Schönberger details in his excellent book Delete: The Virtue of Fogetting in the Digital Age, we have entered a rare time in history where remembering has become the default rather than forgetting. Previous to our present now, the cost of remembering (be that cost monetary or time-intensive) had well exceeded the cost of forgetting. But with the internet storing exponentially the words, acts, and images of our past, along with the reliable searching and aggregating mechanisms enabling efficient retrieval of these data points, our technologies remember while our human minds are still programmed to forget.

Interestingly, Hong Sangsoo's memory-testing oeuvre arose at the very moment when our memories have been augmented by the technologies available to those of us who can afford them. As Viktor Mayer-Schönberger details in his excellent book Delete: The Virtue of Fogetting in the Digital Age, we have entered a rare time in history where remembering has become the default rather than forgetting. Previous to our present now, the cost of remembering (be that cost monetary or time-intensive) had well exceeded the cost of forgetting. But with the internet storing exponentially the words, acts, and images of our past, along with the reliable searching and aggregating mechanisms enabling efficient retrieval of these data points, our technologies remember while our human minds are still programmed to forget.

Hong films don't let you forget even while his characters are forgetting. At the same time his characters are claiming they have excellent memories, (such as in this film with Ku and his mentor artist Yang battling over whose memory is more excellent during one of Hong's obligatory group drinking sessions), Hong's films prove those memories faulty in that the slight variations of similar scenes brings into question the reliability of our memories. Plus, his refusal to prompt dream sequences makes them real while at the same time dreaming the real. And with the modern technology of DVD players, and even more so the inevitable, future searching algorithms that will allow scenes to be searched like Google now allows for the text of books, we can immediately pinpoint the past scenes Hong's films motivate us to recall in their slight variation. Yet Hong demonstrates that even with the expansive external memory banks that film in internet form might provide, each fragmented scene allows for multiple interpretations of meaning, multiple interpretations of meaningless meaning, therein providing their meaning. Hong's films are an endless tape loop, a Möbius strip that collects Escher ants as we travel along its form.

When a college student who was demure to Director Ku outside the classroom before watching his film in class, a film she claims to have seen before, responds bluntly that she doesn't understand why he makes the films he does, arguing, perhaps correctly, that people don't understand his films, Director Ku response is close to an outrage.

"If you don't get it, then you don't. I just make them and the rest is up to you. My films are not dramas that you're used to. No clear messages, ambiguous at best. No beautiful images, either. I can only do one thing. I jump into the process without preconceived ideas. I gather the pieces I discover and make them into one. You might not like the result. No one might."

I swear I've heard Hong make similar comments at post-film Q&A's or conversations I've personally had with him, a clear moment where Hong has brought himself into his film. After questioning Director Ku's proclaimed modesty, stating that his films are irresponsible, she makes the best summary of Hong and why his films fall so flatly on so many, yet resonate so deeply with the small number of us who've grown to love his films, "You're not a film director, but a philosopher." (Adam Hartzell)

Mr. Kim has lost all hope. One day he stands at the edge of one of Seoul's famous bridges that cross the Han River and jumps into the swirling water. All goes black. However the following morning he awakens with the sun in his eyes and his face in the sand. This isn't heaven, he has drifted to one of the small uninhabited islands that lie in the middle of the Han River. At first he is merely frustrated that his suicide was a failure, but soon he realizes that he faces a more immediate problem. There is nobody else on the island -- nothing but plants, trees, the odd duck and bits of trash. The far edge of the river is well within sight, but Kim never learned how to swim. His efforts to contact the mainland fail. He is stranded, there is nothing to eat, and even though he is in the middle of one of the world's major metropolises, he has become a modern-day Robinson Crusoe.

Kim will eat a lot of mushrooms in the coming weeks and months, and his isolation will slowly but surely start to change him. But there is another unexpected character in this drama. A young woman, also with the surname Kim, lives in a riverside apartment building. Like the hikimori portrayed in Bong Joon Ho's "Shaking Tokyo" (from Tokyo!), Ms. Kim is a recluse who has not ventured out of her room for years. One day she is peering out her window with a pair of binoculars when she catches sight of the strange disheveled man on the island. His actions mystify her, and then gradually intrigue her. Eventually she will be moved to do the unthinkable: to step outside her apartment building and enter into a strange sort of communication with him.

Kim will eat a lot of mushrooms in the coming weeks and months, and his isolation will slowly but surely start to change him. But there is another unexpected character in this drama. A young woman, also with the surname Kim, lives in a riverside apartment building. Like the hikimori portrayed in Bong Joon Ho's "Shaking Tokyo" (from Tokyo!), Ms. Kim is a recluse who has not ventured out of her room for years. One day she is peering out her window with a pair of binoculars when she catches sight of the strange disheveled man on the island. His actions mystify her, and then gradually intrigue her. Eventually she will be moved to do the unthinkable: to step outside her apartment building and enter into a strange sort of communication with him.

Castaway on the Moon can lay claim to being one of the more creatively imagined films produced in Korea in recent years. It makes the most out of its unique setting, but at its core it is a fairly simple character-based drama about two sensitive recluses. Director Lee Hey-jun seems to take a special interest in social outsiders. His debut work Like a Virgin, co-directed with his friend and working partner Lee Hae-young, centered on a short, pudgy high school boy who dreams of getting a sex change operation. Both films present their heroes' predicament with warmth, understanding and sense of humor.

For a film such as this, acting is crucial, and Lee succeeded in casting one of contemporary Korean cinema's standout actors in Jung Jae-young (Welcome to Dongmakgol, Someone Special). Jung's deadpan comic performance is a good match with the director's style, and he creates sympathy for his character without ever pandering to the audience's emotions. Ms. Kim is played by Chung Yeo-won, who grew up in Australia and started her career as a pop singer before debuting as an actor. This is her second leading role in a feature film. (Incidentally, she was enrolled as a student in my Practical English class at Korea University back around 2000, but I guess that's neither here nor there...)

If we are meant to see the two central characters in this film as being broadly compatible, there are nonetheless significant differences between them. The man becomes isolated from society by accident, and yet his experience turns him into something greater than his former self (though he may no longer be able to readjust to modern society). The woman isolates herself from society by choice, but this is portrayed as something damaging, as a condition that needs to be overcome. In observing the man and starting to interact with him, she is slowly drawn out. Why is the man's seclusion a positive experience, and the woman's a negative one? Is it simply that the man has gravitated towards a more natural state, while the woman has moved away from it?

Personally, I found this film interesting, but I couldn't shake the feeling that it wasn't quite reaching its potential. I was also left wishing at the end that there had been a bit more real communication between the two leads. However I seem to be in the minority here -- most people I talk to adore this film. For its unique setting if nothing else, it deserves a look. (Darcy Paquet)

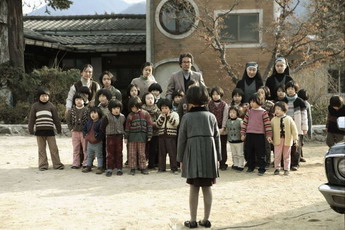

Bong Joon Ho's new film Mother begins with a tease: Do-joon's Mother (Kim Hye-ja, Palace), in an embroidered violet jacket, walks toward the camera through a field of tall grass. Soft jazz-funk begins to play on the soundtrack. Gazing offscreen, she stops walking, then hesitantly starts dancing to the music. We'll see her in the same field later in the movie, but not dancing.

Do-joon's Mother lives with her son Do-joon (Won Bin, Taegugk, Guns and Talks) behind the murky shop where she sells medicinal plants and roots, and practices acupuncture without a license on the side. Do-joon is very good looking (he's played by Won Bin, after all), but he's not quite right in the head, rather like Song Gang-ho's character Gang-du in The Host, and like Gang-du, there is a hint that his impairment is his mother's fault. He's not retarded, but his dullness is difficult to define: he has no attention span to speak of and a poor memory; at twenty-seven he still sleeps with his mom, with a hand on her breast. He hangs around with Jin-tae (Jin Ku, A Dirty Carnival), who's also good-looking in a bad-boy way, and is a bad boy - a tough, cynical hustler who feels constrained by his small-town life and dreams of adventure. Still, Jin-tae seems to have nothing better to do than hang out with Do-joon. He taunts Do-joon for being a virgin at his age. Jin-tae doesn't seem to have any family, and lives alone at the edge of town. There's a lot of this in Mother: one high school character lives with her half-senile, boozing grandmother, intact families are not much in evidence. (For a "traditional" society like Korea, its films and TV dramas feature a surprising number of one-parent families and broken homes.)

Do-joon's Mother lives with her son Do-joon (Won Bin, Taegugk, Guns and Talks) behind the murky shop where she sells medicinal plants and roots, and practices acupuncture without a license on the side. Do-joon is very good looking (he's played by Won Bin, after all), but he's not quite right in the head, rather like Song Gang-ho's character Gang-du in The Host, and like Gang-du, there is a hint that his impairment is his mother's fault. He's not retarded, but his dullness is difficult to define: he has no attention span to speak of and a poor memory; at twenty-seven he still sleeps with his mom, with a hand on her breast. He hangs around with Jin-tae (Jin Ku, A Dirty Carnival), who's also good-looking in a bad-boy way, and is a bad boy - a tough, cynical hustler who feels constrained by his small-town life and dreams of adventure. Still, Jin-tae seems to have nothing better to do than hang out with Do-joon. He taunts Do-joon for being a virgin at his age. Jin-tae doesn't seem to have any family, and lives alone at the edge of town. There's a lot of this in Mother: one high school character lives with her half-senile, boozing grandmother, intact families are not much in evidence. (For a "traditional" society like Korea, its films and TV dramas feature a surprising number of one-parent families and broken homes.)

Do-joon and Jin-tae are already in trouble with the police for vandalizing a Mercedes-Benz that knocked Do-joon down in the street. Then a high-school girl is murdered, and a clue connected to Do-joon is found near her body. Relieved that their first murder case in living memory is so cut-and dried, the police pack Do-joon away. He insists that he didn't kill the girl, though he saw her the night she died. Frantic, his mother sets out to prove Do-joon's innocence. Her blundering efforts draw Jin-tae into helping her to play detective, and they poke around the seamy underside of the town. Jin-tae enjoys himself: "This is in my blood!" he exults after beating up a couple of "suspects," "I should have been a cop." In jail, Do-joon tries to dredge up details from the sieve of his memory, often coming up with details that make matters worse, while his mother closes in on the girl's real killer ... or maybe not ... before returning to that grassy field.

Kim Hye-ja is famous for playing mothers on Korean TV, and it must have been interesting for her to play such a double-edged role. Taking the melodramatic archetype of the Mother to extremes, Kim plays a mother whose symbiosis with her son is nearly complete, yet Bong and Kim manage to keep the character from being monstrous. (The archetype isn't just Korean: the mother who sacrifices everything to save her accused son is a mainstay of American country music, for example.) She does a great job, and one of the main pleasures of the movie is watching her. Won Bin's Do-joon seems like a change from his usual pretty-boy roles, but since the people around Do-joon comment ruefully on his good looks (another of Bong's jokes, I suspect), it's not that big a leap. Jin Ku plays Jin-tae energetically, full of frustrated vitality, and by the end turns out to be a bit more sympathetic than you'd expect.

If you've seen Bong Joon Ho's earlier movies, you'll have some idea what to expect from Mother. Bong says that he chose the English word mother as his title to avoid the associations of the Korean word omoni, but it's probably no coincidence that the Korean pronunciation of mother also sounds like the Korean pronunciation of murder. He likes to build his stories around ordinary people; the characters of his first feature Barking Dogs Never Bite -- a college professor and his salarywoman wife -- were as upscale as he gets. Since then his protagonists have been small-town cops (Memories of Murder), a family that runs a food stand by the Han River (The Host), and now a small-town widow. His manner is operatic: reactions, facial expressions, sound design, even the weather (see the use of rain in Mother) tend to be over the top. Even Won Bin's stupefied look is rapturous in its dullness. Typically for Bong, there are plenty of small jokes at the expense of movie clich?s - misrecognitions, comically inappropriate reactions - jokes that make you wince as you laugh.

In this and in his operatic excesses, Bong is reminiscent of Pedro Almodovar - think of All About My Mother - and if you like Almodovar you may like Bong. (Come to think of it, Lee Byeong-woo's music reminds me of the music in Almodovar's films.) Hong Gyeong-pyo's photography captures the grittiness of decrepit small towns and the working poor; there's a lot of grey and murk, and even the blood looks dark and muddy. Mother is a retreat in scale after the CGI-heavy science-fiction blockbuster The Host, but an advance in confidence and style. It even contains his first sex scene! It's been obvious since Memories of Murder that Bong is a director worth watching, and Mother confirms it. (Duncan Mitchel)

A Catholic chapel in a girl's high school, in a stormy dark night. Four young faces are illuminated by candlelight. Friends who have made a pact to commit suicide, they proceed to climb to the roof of the building. However, only one of them, Eon-joo (Jang Gyung-ah), jumps to her death, her mangled body to be discovered by her shocked sister Jeong-eon (Yoo Shin-ae). The surviving members of the pact, So-yi (Son Eun-seo), Eun-young (Song Min-jeong) and Yu-jin (Oh Yeon-seo), begin to sense the presence of the dead Eon-joo.

The redoubtable Whispering Corridors series, not only one of the few successful film franchises in Korean cinema but also a platform through which many talented actresses have been launched into stardom (Gong Hyo-jin, Kim Min-seon, Song Ji-hyo and Kim Ok-vin to name just a few), is celebrating its tenth anniversary in 2009. Given the disastrous environment in which Korean filmmakers have struggled in the last few years, perhaps we should just be thankful that the series was able to come back at all. Unfortunately, the fifth installment is probably the most generic and lackluster of the lot.

The redoubtable Whispering Corridors series, not only one of the few successful film franchises in Korean cinema but also a platform through which many talented actresses have been launched into stardom (Gong Hyo-jin, Kim Min-seon, Song Ji-hyo and Kim Ok-vin to name just a few), is celebrating its tenth anniversary in 2009. Given the disastrous environment in which Korean filmmakers have struggled in the last few years, perhaps we should just be thankful that the series was able to come back at all. Unfortunately, the fifth installment is probably the most generic and lackluster of the lot.

This does not mean that A Blood Pledge is devoid of any merit. Director Lee Jong-yong, promoted from assistant work for Park Chan-wook's JSA, while taking on an ultra-topical subject of group suicide, goes for the jugular. I find his refusal to burden the film with superficial discussions of the malaise of Korean school system as well as his decision to resolutely stick to the conventions of Gothic horror (this is the kind of movie in which an important prop symbolizing political power is a key to the Catholic chapel, preserved in a velvet-inlaid, ornate jewel box) rather admirable. Sure, some of the scare tactics are obvious, but what do you expect from a summer horror film?

And yet, director Lee also takes some critical missteps, avoided by all other helmers of the series so far. He over-burdens his young actresses with reams of convoluted, emotive expository dialogue, few of which actually serve to enlighten the viewers. Poor girls struggle through the breathless sentences like rookie recruits in a boot camp with extra-heavy backpacks: only Yoo Shin-ae emerges relatively unscathed. Despite his visible effort to construct a decent psychological mystery, director Lee's failure to create three-dimensional characters leave us rather blas? about the ultimate motivation behind Eon-joo's haunting. Finally, the film has two or three truly embarrassing moments of non-special effects, including a laughable "exploding head" gag that I sincerely hope will be deleted from the export version.

While not the worst Korean horror film in recent memory by a long shot (Are you kidding? Oetori? Death Bell?), A Blood Pledge is nonetheless a disappointment. Lacking the elegant lyricism of Memento Mori, the disturbing metaphysical implications of Voice, or even the lurid psychodrama of Wishing Stairs, A Blood Pledge is an obtusely "sincere" horror film in a series known for a remarkable mixture of ingeniously induced frisson and unexpectedly moving art-house touches. (Kyu Hyun Kim)

Min-seo is a high school student who feels frustrated and angry at the state of her life. Her friends all take after-school classes at study institutes, but her single mother can't afford to pay for them. With her mother preoccupied with a new boyfriend, Min-seo has nothing to do during the hours after school (that is, if she goes to school), and she eventually gets an under the table job at a massage parlor in order to pay for English classes.

One day she is riding the bus when a migrant worker from Bangladesh drops his wallet. The man exits the bus, and Min-seo takes the wallet for herself. However the man, named Karim, soon realizes what happens and manages to chase Min-seo down in a side street. "Let's go to the police station," he says in excellent Korean, but Min-seo manages to talk herself out of trouble. Instead, she eventually agrees to help him with a problem that has long haunted him: trying to collect his back wages from a former employer who refuses to pay him.

One day she is riding the bus when a migrant worker from Bangladesh drops his wallet. The man exits the bus, and Min-seo takes the wallet for herself. However the man, named Karim, soon realizes what happens and manages to chase Min-seo down in a side street. "Let's go to the police station," he says in excellent Korean, but Min-seo manages to talk herself out of trouble. Instead, she eventually agrees to help him with a problem that has long haunted him: trying to collect his back wages from a former employer who refuses to pay him.

Min-seo and Karim are one of the more interesting pairings in 2009 Korean cinema. Min-seo is particularly well drawn: rebellious and not particularly nice, she is an unpredictable and magnetic screen presence. Although at first her actions are driven by a kind of self-focused anger, as the film goes on and she draws closer to Karim, her anger takes on a different quality. The young actress Baek Jin-hui puts tremendous life into this performance, and her character is without question the best thing in this film.

Karim is played by Mahbub Alam, a longtime resident of Korea who entered the country as a migrant worker and who has since become involved in various activist projects, including the launch of the Seoul Migrant Workers Film Festival. He shows himself to be a decent actor in this film, as well as an accomplished Korean speaker, although his character lacks the sort of emotional complexity that we see in Min-seo. (Alam also appeared briefly in Where Is Ronny?, another film from 2009 that explores Korean attitudes towards Southeast Asian minorities.)

In a sense, Bandhobi is two films in one: a story about two people from very different backgrounds who come to form a close bond, and a piece of social commentary about discrimination against migrant workers in Korea. If the latter had been executed as effectively as the former, this film would have been a major achievement. Alas, there is a one-dimensional quality to the film's political content that clashes with its three-dimensional characters. Every time we see Karim interacting in Korean society, someone discriminates against him. This may well be true to the experiences of many migrant workers, but within the film itself it becomes so predictable that the director's intention crowds out everything else.

This is a rare misstep for Shin Dong-il, who in the past five years has established himself as one of the most interesting among the Korean directors who haven't yet become famous. His previous works, including Host & Guest (2005) and My Friend & His Wife (2006), have also drawn attention to social issues and class differences through well-developed, complex characters and relationships. Bandhobi's best scenes capture the viewer's attention in a powerful, involving way. If Shin let his politics become a little too obvious this time, other aspects of his filmmaking are still in top form. In this case, even a partially realized effort is well worth watching. (Darcy Paquet)

Patrolman Kim (Uhm Tae-woong, Handphone, Family Ties) is kicked off to a mountain town due to a jokey report he filled in, supposedly idyllic and crime-free. The town's mayor and other bigwigs are scheming to bring in and scalp the Seoul folks eager to experience "organic farming." There is only one problem: the surrounding area's food-chain imbalance has unleashed a steamroller-sized boar that has developed taste for human flesh. After it devours a few townies, including the veteran game hunter Cheon Il-man's (Jang Hang-sun, Tell Me Something, The Foul King) daughter, the big-shots reluctantly organize an ad hoc team of boar hunters, led by a Finland-trained professional Baek Man-bae (Yun Je-mun, The Host, Mother). Tagging along with Il-man and Man-bae, who promptly rekindle an unresolved father-son conflict from the past, are hapless Patrolman Kim, wild boar expert Soo-ryun (Jeong Yu-mi, Family Ties, Blossom Again) and the shades-wearing Detective Shin (Park Hyuk-kwon, Open City, TV's The Great White Tower).

Chaw (This apparently means "trap" in Chungcheong Province dialect) is a mighty strange movie, even considering that it is about a man-eating pig(Seriously, a wild boar is plenty persuasive as a movie monster, as Russell Mulcahy's Razorback, among others, testifies). For about its first third, the movie seems willing to stick to the conventions of monster-on-the-rampage films, introducing innocent victims to be slaughtered and showing the town's effort to whitewash real dangers for the tourists, a la Jaws. Then the film begins to mutate into a horror comedy with positively bizarre setups and wildly surrealistic touches.

Chaw (This apparently means "trap" in Chungcheong Province dialect) is a mighty strange movie, even considering that it is about a man-eating pig(Seriously, a wild boar is plenty persuasive as a movie monster, as Russell Mulcahy's Razorback, among others, testifies). For about its first third, the movie seems willing to stick to the conventions of monster-on-the-rampage films, introducing innocent victims to be slaughtered and showing the town's effort to whitewash real dangers for the tourists, a la Jaws. Then the film begins to mutate into a horror comedy with positively bizarre setups and wildly surrealistic touches.

For sure, some of the film's off-kilter humor had the preview audience in stitches: an Aliens parody in which a snickering local cop, sequestered in a cockpit-like driver's seat of an excavator, gets down mano-a-bestia with the very angry boar, for example, is simply priceless. Yet, for every one of these winners, there is another totally mind-boggling scene like Baek-man's dog hurling sarcasm at him telepathically (?) in Russian (??), or the town's resident madwoman smoking opium (?) reclining in her forest abode, where multicolored mushrooms (???) sprout everywhere. By the two-thirds of the film, you might indeed be wondering just what substance Director Shin Jung-won (whose previous film, To Catch A Virgin Ghost, was dopey-crazy in the same style, but not to this extent) had himself been partaking of in the course of production.

The surprise, then, is that, despite all these bizarre touches and weird goings-on, Chaw ultimately registers as superior entertainment. Let's be clear about one thing, though: Shin displays little aptitude for an action thriller. He's no Spielberg--shucks, he's not even Joe Dante: Chaw's big monster is simply lame, especially whenever it has to ever so slowly chase after hapless humans. In terms of special effects, too, the hog ranks somewhere between the levels of "Acceptable" and "Pathetic."

Chaw's strengths lie elsewhere. For one, it is blessed with an excellent cast who convincingly rattle off its insanely colorful dialogue. Even though the characters are sometimes thoroughly unrealistic, they are nonetheless hugely attractive. Most importantly they don't insult the viewer's intelligence: for instance, Detective Shin actually deduces that there is indeed a man-eating pig from the clues he put together. Their arcs intersect in pleasantly surprising ways, too: Soo-ryun's relentless sunny disposition turns out to be a perfect antidote to Man-bae's camouflage of hardened cynicism. At the center of all these crazy antics, Uhm Tae-woong is perfect as our (relatively speaking) normal hero: his absurdly commonsensical response to the surrounding chaos becomes mercilessly hilarious by the climax.

Part Monty Python-like parody of Hollywood disaster films, part conventional monster horror, part surrealist situation comedy (?), Chaw is the kind of film that makes you shake your head in disbelief more than once, but also keeps you laughing. I do wish Shin had reined in some of the film's excesses (including an afterthought-like epilogue that explains the ultimate fate of a character) and was given a chance to improve on the creature design and execution of special effects, but what ended up on screen, while lacking in bite, has a pleasing, unique flavor of its own. (Kyu Hyun Kim)

Haeundae became the fifth South Korean film to break the 10 million admissions mark. It made a lot of money, but it didn't make much else.

That's a trite statement, I know. Typing such a statement requires I ignore the fact that in making a lot of money, that money spread around the Korean peninsula like the pixilated tidal waves of the film throughout the beaches of Haeundae. And depending on how that money was spent elsewhere in the economy, it made other things. By creating a financially successful blockbuster, it allowed for friends, families, and both well-trenched and tentative romantic partners to create an eventful evening. And more with the money, they possibly ate before or after the film at an independently-owned restaurant or drank coffee before or after the film at a corporate coffeehouse. But as for giving us something to talk about as a cultural touch point with lasting power, there's not much there. Even Shiri brings up even more interesting things to discuss than Haeundae.

But talk about it we must, because this website is as much a film aggregator as it is a place for pinpointing the significance of South Korean films. So let's get the plot out of the way. Claiming to be South Korea's first disaster movie, director Youn Je-gyun (Sex Is Zero and My Boss, My Hero who also goes by just 'JK Youn') takes advantage of Busan's tourist beaches as an opportunity to destroy tall buildings and holiday-goers with a tsunami. With the devastation caused by a tsunami in Thailand a few years back, non-diegetic fears and images travel along the current of the computer-generated images of insanely-storey-ed waves.

But talk about it we must, because this website is as much a film aggregator as it is a place for pinpointing the significance of South Korean films. So let's get the plot out of the way. Claiming to be South Korea's first disaster movie, director Youn Je-gyun (Sex Is Zero and My Boss, My Hero who also goes by just 'JK Youn') takes advantage of Busan's tourist beaches as an opportunity to destroy tall buildings and holiday-goers with a tsunami. With the devastation caused by a tsunami in Thailand a few years back, non-diegetic fears and images travel along the current of the computer-generated images of insanely-storey-ed waves.

Here are the characters we are asked to care about. There is a wealthy young woman on holiday with friends from Seoul who falls for a local member of the Coast Guard. We also have a seaman (Sol Kyung-gu, a great actor choosing yet another bad film, although I'm sure he got paid nicely) who longs for the daughter of a fellow seaman. Unfortunately, that fellow seaman died while at sea during a tsunami years ago and our surviving seaman feels responsible for his death, which leaves our survivor hesitant in consummating his affections for the daughter. Then there's the geologist (Park Joong-hoon returns!) who has a genre-demanding, outlandish theory about mega-tsunamis which the genre equally demands his colleagues find unconvincing. Plus, he provides a third love interest storyline when he runs into his divorced wife who has a daughter he thinks he's seen somewhere before (such as his mirror, because it's his daughter but his daughter doesn't know that). Still more, we have an ambitionless adult child frustrating his mother. And rounding things off is the misunderstood hotel developer.