Essays from the Far East Film Festival

by Darcy Paquet

The Far East Film Festival in Udine, Italy held its first edition in 1998 with a special focus on popular films from Hong Kong. Since then, the event has grown in size and expanded to encompass works from across East and Southeast Asia. The festival specializes in popular films that are often not shown by other festivals, in the hopes of providing a snapshot of how cinema fits within overall trends in Asian popular culture. The FEFF also hosts many retrospectives: examples include the Asian musical, director Patrick Tam, Nikkatsu action films from Japan, and Korean films of the 1970s. More information about the festival can be found at http://www.fareastfilm.com.

I've been working for the FEFF, and contributing essays to their catalogue, since 2002. The following essays are reprinted with permission from the organizers. The main essay for each year covers general commercial and artistic trends within the previous 12 months (the catalogue is printed during the festival in late April, so I usually write them in February or March). Note that I mostly, but not exclusively, focus my comments on the Korean films screened in Udine each year. I hope that through these essays, readers can get a general sense of what issues had people talking in each given year.

Still Waiting for Good News: Korean Cinema in 2021

Another year has passed for the Korean film industry, and it finds itself in much the same state that it was in spring 2021. South Korea has weathered the pandemic better than most countries, all things considered, but moviegoing is a habit that many citizens have been content to give up in difficult times. As recently as 2019, South Korea had the highest rate of theatrical attendance in the world, with an average 4.37 films seen per capita. In 2021, by contrast, per capita attendance fell to 1.17. What it will take to re-instill that habit in the broader public is the primary question facing the Korean film industry today.

Let's rewind for a moment to May of 2021. Korean film studios and exhibitors were facing a dilemma. It was highly uncertain at that time if there would be any sort of summer box office season, or if theaters would continue to remain empty through the traditionally peak months of July and August. The spring had offered little in the way of encouragement, with high profile features The Book of Fish (pictured right) and Seobok both performing far below expectations. But the imminent return of Hollywood blockbusters to the theater after a year-long absence brought at least some hope for a partial revival. No one expected a return to 2019 levels, of course, but the question was, would it make economic sense to release any of the numerous big-budget Korean films that had been stuck in limbo since early 2020?

Let's rewind for a moment to May of 2021. Korean film studios and exhibitors were facing a dilemma. It was highly uncertain at that time if there would be any sort of summer box office season, or if theaters would continue to remain empty through the traditionally peak months of July and August. The spring had offered little in the way of encouragement, with high profile features The Book of Fish (pictured right) and Seobok both performing far below expectations. But the imminent return of Hollywood blockbusters to the theater after a year-long absence brought at least some hope for a partial revival. No one expected a return to 2019 levels, of course, but the question was, would it make economic sense to release any of the numerous big-budget Korean films that had been stuck in limbo since early 2020?

It was a bit of a chicken-and-egg problem. The only thing likely to pull casual viewers of all ages to the theater was the marketing hype, media attention and word-of-mouth excitement that a big-budget local film could provide. So exhibitors were hoping that Korean distributors would schedule their blockbusters for the summer. But from the distributors' point of view, it was tremendously risky to release such expensive movies in such uncertain times. Only millions of ticket sales would ensure a chance of turning a profit, so they preferred to wait until more positive signs emerged at the box-office.

Initially, attention turned to the Hollywood films opening in late spring. The first of these, Fast & Furious 9, sold 2.3 million tickets in late May. Disney's Cruella, released in the same month, sold 1.2 million tickets. Such numbers were not bad, but neither were they particularly encouraging. One by one, distributors who had considered releasing big-budget films in the summer announced they would delay further.

It was at this point that exhibitors, desperate to avoid a lost summer, decided to make a deal. In normal times, theaters will keep roughly half of the revenue earned from ticket sales, with the other half going to the film company. But for the summer of 2022, they agreed that Korean film companies could keep 100% of the revenues from ticket sales until they had recovered the cost of making the film. After that point, revenues would be divided as usual.

This temporary deal briefly transformed the economics of film releases. Although some of the major distributors declined to join in, three Korean blockbusters ultimately went ahead and opened in the summer. The first of these was director Ryoo Seung-wan's Escape from Mogadishu. Shot in Morocco, and having wrapped production just weeks before the start of the pandemic, Escape from Mogadishu is based on a true story of a group of North and South Korean diplomats trapped in the civil war which broke out in Somalia at the end of 1991. Featuring a talented ensemble cast, a highly dramatic story and some jaw-dropping spectacle, this was a film that in ordinary times would be a sure bet to sell 10 million tickets. Upon its release in late July, reviews and word-of-mouth were both strong, nonetheless an unfortunately-timed surge in case numbers with the arrival of the Delta variant had a dampening effect on its performance. With its large production budget, Escape from Mogadishu would ordinarily have to sell over 6 million tickets to cover its costs, but under the new deal with the theater chains, the break-even point was 3.4 million tickets. Ultimately, an extended but steady run in theaters left the film with 3.6 million tickets sold -- enough for a slight profit, and to overtake Black Widow as the top-grossing film of the summer.

This temporary deal briefly transformed the economics of film releases. Although some of the major distributors declined to join in, three Korean blockbusters ultimately went ahead and opened in the summer. The first of these was director Ryoo Seung-wan's Escape from Mogadishu. Shot in Morocco, and having wrapped production just weeks before the start of the pandemic, Escape from Mogadishu is based on a true story of a group of North and South Korean diplomats trapped in the civil war which broke out in Somalia at the end of 1991. Featuring a talented ensemble cast, a highly dramatic story and some jaw-dropping spectacle, this was a film that in ordinary times would be a sure bet to sell 10 million tickets. Upon its release in late July, reviews and word-of-mouth were both strong, nonetheless an unfortunately-timed surge in case numbers with the arrival of the Delta variant had a dampening effect on its performance. With its large production budget, Escape from Mogadishu would ordinarily have to sell over 6 million tickets to cover its costs, but under the new deal with the theater chains, the break-even point was 3.4 million tickets. Ultimately, an extended but steady run in theaters left the film with 3.6 million tickets sold -- enough for a slight profit, and to overtake Black Widow as the top-grossing film of the summer.

Disaster movie Sinkhole, about a family who is trapped when a giant sinkhole swallows up their apartment building, came in second among Korean releases with 2.2 million admissions. Offering up a familiar blend of comedy and CGI-heavy effects, the film was less warmly embraced by critics but still found a decent-sized audience.

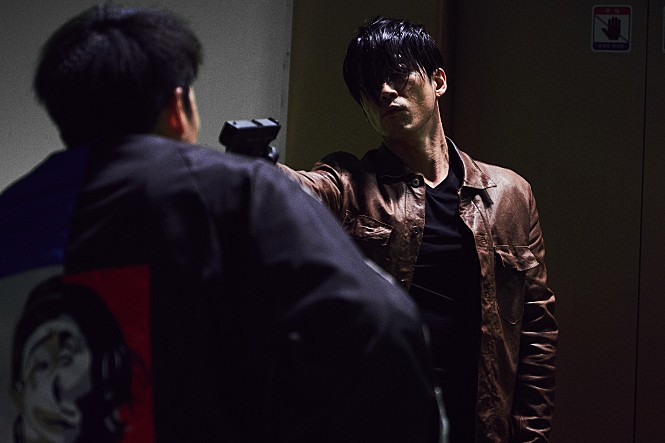

The third major release of the summer relied more on concept and execution, rather than special effects or a blockbuster-scale budget. Hostage: Missing Celebrity by debut writer-director Pil Gam-seong features top star Hwang Jeong-min playing himself, in a fictional story about the actor being kidnapped and held for ransom. In keeping with the concept, the director decided to cast largely unknown actors in the other roles to heighten the film's sense of reality. Tense and dramatic, the film was well-received after its mid-August release, and sold a total of 1.6 million tickets.

The third major release of the summer relied more on concept and execution, rather than special effects or a blockbuster-scale budget. Hostage: Missing Celebrity by debut writer-director Pil Gam-seong features top star Hwang Jeong-min playing himself, in a fictional story about the actor being kidnapped and held for ransom. In keeping with the concept, the director decided to cast largely unknown actors in the other roles to heighten the film's sense of reality. Tense and dramatic, the film was well-received after its mid-August release, and sold a total of 1.6 million tickets.

The combination of some innovative dealmaking, and a willingness to take risks by the film companies involved (particularly production company Filmmakers R&K, which produced both Escape from Mogadishu and Hostage: Missing Celebrity), resulted in a partial win for Korean cinema in the summer of 2021. Surely, if there had been no summer box office season, the psychological and financial hit to the industry would have been more severe. And in the end, these three releases would rank as the best-selling Korean films not only in the summer, but for the year as a whole.

The fall season was marked by continued struggles with COVID and some moderate successes at the box office. The Chuseok holiday in September, another traditionally strong period for Korean films, saw two major releases: thriller On the Line from CJ Entertainment, and the rural-set drama Miracle: Letters to the President from Lotte Entertainment. The latter film, based on a true story, earned less at the box office but is the more memorable of the two, with its assured acting performances and touching story about family, talent and ambition. Director Lee Jang-hoon, whose debut feature Be With You (a Far East Film Festival 20 selection) was a solid hit in 2018, is marking himself as an important new voice in the genre of family melodrama.

Later in the fall, a pleasant surprise emerged with the release of Perhaps Love, the feature directorial debut of well-known actress Cho Eun-ji (The Villainess). A bold comedy about a famous but troubled novelist (Ryu Seung-ryong) and his tangled personal life, the film features an unforgettable cast of characters and some of the funniest moments provided by Korean cinema in 2021. Despite the challenges it faced at the box office, Perhaps Love amassed 500,000 admissions and marked out its director as a key talent to watch.

Later in the fall, a pleasant surprise emerged with the release of Perhaps Love, the feature directorial debut of well-known actress Cho Eun-ji (The Villainess). A bold comedy about a famous but troubled novelist (Ryu Seung-ryong) and his tangled personal life, the film features an unforgettable cast of characters and some of the funniest moments provided by Korean cinema in 2021. Despite the challenges it faced at the box office, Perhaps Love amassed 500,000 admissions and marked out its director as a key talent to watch.

The autumn may have been a grim time overall for Korean cinema, but that doesn't mean people weren't talking about Korean content. The release of Netflix series Squid Game in September and its astounding worldwide success had all of Korea buzzing. Much of the talent behind Squid Game were longstanding contributors to Korean cinema, from director Hwang Dong-hyuk -- whose previous works Miss Granny and Silenced (an FEFF Audience Award winner) will be familiar to audiences in Udine -- to leading actor Lee Jung-jae and his nearly three decades of experience in Korean film. Seeing this team succeed to such a degree on Netflix's platform was both encouraging and exciting, but also bittersweet for people in the film industry. With movie theaters hobbled by the pandemic, and Netflix investing $500 million per year in Korean content, the large-scale migration of talent to OTT platforms was hard to witness without a certain degree of alarm. For the comparatively few Korean feature films entering production in 2021, competition to secure the services not only of actors but also directors and all manner of production crew made the situation even more difficult.

As winter came, Korea experienced an unprecedented surge in COVID cases, despite vaccination rates of more than 90% among adults. Big-budget tentpoles that had decided to sit out the summer saw even less reason to take a chance on the winter box office season. Ironically, however, in the midst of the COVID surge Spider-Man: No Way Home opened and powered its way to 7.6 million admissions -- easily the best performance of the pandemic period. This was a much-needed boost to theater chains, and provided some reassurance that moviegoing was not yet dead. Nonetheless it played out largely as a one-off success, not leading to any broader recovery in box office admissions. The single blockbuster-scale Korean release of the winter, Lotte Entertainment's The Pirates: The Last Royal Treasure, topped out at 1.3 million admissions, not near enough to cover its massive budget.

Nonetheless, a few mid-sized Korean films opened in January and drew some attention. Special Delivery (pictured right) is an action film in which Park So-dam ('Jessica' from Bong Joon Ho's Parasite) plays an expert driver on the run from a corrupt detective. Filled with energy and personality, the film earned yet more praise for the talented Park in her first action role. Then a few weeks later, a much heavier drama burst onto the scene. Kingmaker is a thinly-veiled depiction of the events leading up to Korea's 1971 presidential election, in which the authoritarian president Park Chung Hee was nearly unseated by the upstart (and future president) Kim Dae Jung. A political drama with much to say about the tension between power and ideals, the release was even more relevant given that Korea was in the midst of a contemporary presidential campaign.

Nonetheless, a few mid-sized Korean films opened in January and drew some attention. Special Delivery (pictured right) is an action film in which Park So-dam ('Jessica' from Bong Joon Ho's Parasite) plays an expert driver on the run from a corrupt detective. Filled with energy and personality, the film earned yet more praise for the talented Park in her first action role. Then a few weeks later, a much heavier drama burst onto the scene. Kingmaker is a thinly-veiled depiction of the events leading up to Korea's 1971 presidential election, in which the authoritarian president Park Chung Hee was nearly unseated by the upstart (and future president) Kim Dae Jung. A political drama with much to say about the tension between power and ideals, the release was even more relevant given that Korea was in the midst of a contemporary presidential campaign.

With February and March showing no further signs of a breakthrough, the film industry once again finds itself gazing into the near future, not knowing whether the industry will finally turn a corner in the coming months, or whether the downturn will persist. The Omicron wave in Korea has been so many times bigger than anything that has preceded it, that one expects when it does finally recede, citizens will feel more at ease out in public. A cautious optimism for the upcoming summer season seems to be taking hold among local distributors. Film festivals, at least, are returning in force; after a partial revival of the Busan International Film Festival in October (in-person screenings at 50% capacity, though with no parties and few international guests), the Jeonju International Film Festival in May is planning for a return to its former scale.

Meanwhile, the crisis brought on by the pandemic has given members of the Korean film industry much time to think about the present and future of Korean cinema. One issue that continues to receive much attention is the need for further diversity in Korean cinema. Independent films have felt as vital as ever during the pandemic, with new voices emerging every year. 2021 saw quite a few independent films attract attention, including the major prizewinner The Apartment With Two Women by debut director Kim Se-in. A startlingly intense family drama about a single mother and her 20-year old daughter, the film screened at Busan and Berlin, and is just getting started on what is sure to be a long festival career. This year's FEFF will highlight several exciting independent works, from the genre-inflected Thunderbird produced by the Korean Academy of Film Arts, to acclaimed documentaries Fanatic and Kim Jong-boon of Wangshimni.

Meanwhile, the crisis brought on by the pandemic has given members of the Korean film industry much time to think about the present and future of Korean cinema. One issue that continues to receive much attention is the need for further diversity in Korean cinema. Independent films have felt as vital as ever during the pandemic, with new voices emerging every year. 2021 saw quite a few independent films attract attention, including the major prizewinner The Apartment With Two Women by debut director Kim Se-in. A startlingly intense family drama about a single mother and her 20-year old daughter, the film screened at Busan and Berlin, and is just getting started on what is sure to be a long festival career. This year's FEFF will highlight several exciting independent works, from the genre-inflected Thunderbird produced by the Korean Academy of Film Arts, to acclaimed documentaries Fanatic and Kim Jong-boon of Wangshimni.

Nonetheless, the election of conservative candidate Yoon Suk-yeol in March to a 5-year term as president is seen as an ominous sign for independent filmmakers. The previous administration had boosted its financial support to independent cinema, providing a much-needed lifeline in difficult times. But if Yoon follows the example of previous conservative presidents, such support may well dry up in the coming years.

One also senses changes taking place within the realm of genre cinema. Up until now, Korean audiences have never fully embraced low-budget genre films, in contrast to many markets in Europe. The thrillers for which Korean cinema is famous have been produced mostly as mainstream commercial features with sizable budgets. And yet the genre films being produced in Korea these days are showing much broader range in terms of scale and budget. Widening distribution options on OTT and other platforms, as well as expanding opportunities for international distribution, has meant that mid-range and lower-budget action films, thrillers and horror movies enjoy more of a second life after their theatrical runs.

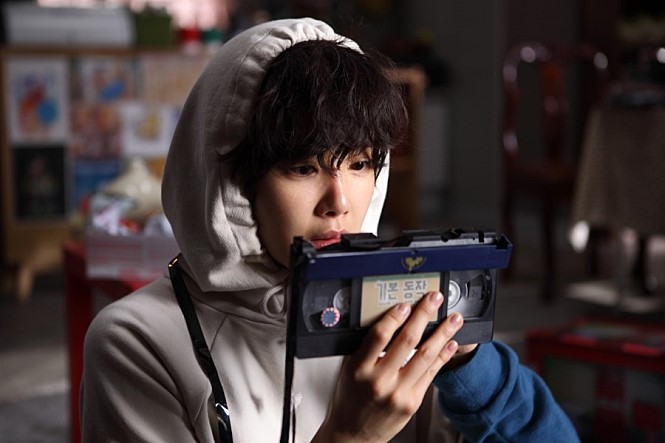

This year's FEFF features several notable action films in its program. Tomb of the River adopts the seaside city of Gangneung as the setting for a classic tale of betrayal and gang warfare. The film features veteran actor Yoo Oh-sung (Friend) and Jang Hyuk as two gangsters of opposite temperament destined to collide. Jang Hyuk also takes the lead role in The Killer, (pictured right) continuing his late career reinvention as a formidable action star. The film, which receives its world premiere in Udine, has already secured distribution deals to 23 international territories.

This year's FEFF features several notable action films in its program. Tomb of the River adopts the seaside city of Gangneung as the setting for a classic tale of betrayal and gang warfare. The film features veteran actor Yoo Oh-sung (Friend) and Jang Hyuk as two gangsters of opposite temperament destined to collide. Jang Hyuk also takes the lead role in The Killer, (pictured right) continuing his late career reinvention as a formidable action star. The film, which receives its world premiere in Udine, has already secured distribution deals to 23 international territories.

There's no question that Korean cinema finds itself at an interesting crossroads in its development. Worldwide interest in Korean content only seems to be getting stronger, but the pandemic has temporarily pushed the film industry aside, as acclaimed series on Netflix and other platforms gather international attention. Clearly, the Korean film industry still has the talent and know-how to be successful. But can it survive shifting market forces and the lingering effects of the pandemic to regain its former glory? One suspects that 2022 may provide an answer to this question -- but it's not yet clear what the answer will be.

Stalled: Korean Cinema in 2020

Following the Korean film industry over the past 12 months has been a bit like watching a sports car stalled at the side of the road. With great effort and a bit of ingenuity, the driver just manages to start the engine... but after creeping forward a short distance, the engine kicks out again. You know that this is a vehicle that can travel at impressive speeds, but for the time being, it is stuck.

A year ago, as spring ended and the (in usual times) peak summer box office season approached, the audience seemed to be on the fence. South Korea's first major COVID-19 outbreak had taken place in February, and it was clear that the pandemic was not going away anytime soon. But authorities had brought it under control with an effective test-and-trace strategy, keeping the average number of new cases to about 50 per day.

Movie theaters were seen by the general public as a particularly dangerous place to be spending time during a pandemic, but the film industry was trying to change the narrative. In reality, universal mask use and the high ventilation standards in place for movie theaters meant that theatrical screenings were quite safe. Even a year later, not a single person in Korea has been confirmed to have caught COVID-19 at a movie theater. But it was clear that audiences would only consider returning to the theater en masse if the disease were beaten back more generally in society.

There was also the lack of high-profile content in theaters. Hollywood releases dried up almost completely, as in the rest of the world. Korean distributors too pulled all their major releases in the first part of the year, but by June they were debating whether to test the waters. Innocence, a mid-budgeted, highly melodramatic legal thriller released on June 10, exceeded expectations by amassing close to 900,000 admissions (about US$7 million). The zombie thriller #Alive (pictured left), which would go on later to find an international audience through Netflix, sold 1.9 million tickets (close to $15 million) after its June 24 release in theaters.

There was also the lack of high-profile content in theaters. Hollywood releases dried up almost completely, as in the rest of the world. Korean distributors too pulled all their major releases in the first part of the year, but by June they were debating whether to test the waters. Innocence, a mid-budgeted, highly melodramatic legal thriller released on June 10, exceeded expectations by amassing close to 900,000 admissions (about US$7 million). The zombie thriller #Alive (pictured left), which would go on later to find an international audience through Netflix, sold 1.9 million tickets (close to $15 million) after its June 24 release in theaters.

Such numbers convinced local distributors to gamble on the summer season. Although not all the planned releases went through, distributor N.E.W. decided to go ahead and slot in Peninsula, one of the year's most anticipated films, for a July 15 release. A big-budget sequel of sorts to the 2016 runaway hit Train to Busan, Peninsula centers around a Korean soldier in Hong Kong who takes up a gangster's offer to infiltrate the zombie-infested Korean peninsula to liberate a truckful of cash. In the end, despite lukewarm reviews, the film performed well, grossing 3.8 million admissions (adding up to roughly US$30 million) in Korea, and also topping the box office in other parts of Asia that had contained the virus well. It seemed like a proper summer season was taking shape.

Steel Rain 2, a political thriller that is a sequel in name only to the original Steel Rain (2017) - it imagines a wholly different doomsday scenario, involving the leaders of South Korea, North Korea and the US all taken hostage on a nuclear submarine - opened on July 29 and had middling success. Its 1.8 million admissions is less than half that of the original film, but still good enough for revenues of about $13 million.

Unexpectedly, the winner of the summer box office season turned out to be not Peninsula, but Deliver Us from Evil, an action thriller set mostly in Thailand. The film stars Hwang Jung-min as a veteran assassin who rushes to Bangkok to save his kidnapped daughter. With impressively staged action sequences, striking cinematography by Parasite DoP Hong Kyeong-pyo, and several memorable performances including Lee Jung-jae as the stylish and menacing villain Ray, Deliver Us from Evil topped 2 million admissions after only 5 days on release. On its 18th day on release it reached 4 million admissions (US$32 million), but by then events had already turned for the worse.

Unexpectedly, the winner of the summer box office season turned out to be not Peninsula, but Deliver Us from Evil, an action thriller set mostly in Thailand. The film stars Hwang Jung-min as a veteran assassin who rushes to Bangkok to save his kidnapped daughter. With impressively staged action sequences, striking cinematography by Parasite DoP Hong Kyeong-pyo, and several memorable performances including Lee Jung-jae as the stylish and menacing villain Ray, Deliver Us from Evil topped 2 million admissions after only 5 days on release. On its 18th day on release it reached 4 million admissions (US$32 million), but by then events had already turned for the worse.

It was an extensive cluster infection at a conservative church, combined with a massive anti-government rally organized in part by the leader of that church, that led to a sharp rise in cases not only in Seoul, but in the rest of the country as well. Although not on the scale of outbreaks in other countries (the August wave peaked at 441 positive tests on a single day), it had a huge effect on the nation's psyche. Attendance at theaters plunged.

One film that suffered from particularly unfortunate timing was the action comedy OK! Madam, starring Uhm Jung-hwa. The story of a family who wins a trip to Hawaii but then has their plane hijacked by North Korean terrorists, OK! Madam opened on August 12, hoping to take advantage of the three-day weekend from August 15-17 that was predicted to bring box office gold. Instead, cases began to spike on August 14, dominating the news cycle and resulting in many canceled ticket reservations. The film ended up selling a total 1.2 million tickets.

Case counts stabilized somewhat in September and October, but the damage had been done. For much of the mainstream audience, moviegoing shifted into the mental category labeled "things to do after the pandemic is over." During the Chuseok holiday at the end of September, traditionally a boom time at the box office, case counts were actually quite low, but theaters remained deserted. Distributors that had hoped for a rebound ended up suffering the consequences. Cult director Shin Jung-won's eccentric Night of the Undead, despite being a thoroughly enjoyable and hilarious film, bombed at the box office with just over 100,000 admissions. Two weeks later, the critically acclaimed debut film Voice of Silence (pictured left) featuring the very popular Yoo Ah-in only managed to secure 400,000 admissions.

Case counts stabilized somewhat in September and October, but the damage had been done. For much of the mainstream audience, moviegoing shifted into the mental category labeled "things to do after the pandemic is over." During the Chuseok holiday at the end of September, traditionally a boom time at the box office, case counts were actually quite low, but theaters remained deserted. Distributors that had hoped for a rebound ended up suffering the consequences. Cult director Shin Jung-won's eccentric Night of the Undead, despite being a thoroughly enjoyable and hilarious film, bombed at the box office with just over 100,000 admissions. Two weeks later, the critically acclaimed debut film Voice of Silence (pictured left) featuring the very popular Yoo Ah-in only managed to secure 400,000 admissions.

Any hopes that the winter holiday season might give the film industry a bit of a rebound were crushed by a COVID third wave that was worse than anything before or since. Ironically, the peak number of new cases (1,241 in one day) came on Christmas, a holiday that in normal times could be expected to be a box office bonanza. But by then, all the major blockbusters that had considered a release, including CJ Entertainment's Seobok, had been postponed to a later date.

Early 2021 offered little in the way of respite, except for two foreign animated releases that enjoyed sustained long-term success. Pixar's Soul, released on January 20, earned glowing reviews and amassed a total of 2 million admissions. Even more successful was Demon Slayer: Mugen Train from Japan, which opened a week later and slow-burned its way to a total of 2.1 million admissions. But the Korean films which opened in theaters - mostly lower profile genre films and independent releases - failed to generate much of an audience.

Ultimately, only one big-budget local movie went through with a release in spring 2021. Seobok - a futuristic action film about the world's first human clone who develops special powers, but escapes from his research team - boasted considerable star power in its male leads Gong Yoo and Park Bo-gum, as well as ambitious special effects. It was released on April 15, which is not usually a strong season for moviegoing, but CJ hedged its bets by opening it simultaneously on its own OTT platform TVing. It's not clear how many viewers tuned in to watch Seobok at home, but in theaters at least, the returns were low with 385,000 ticket sales.

Ultimately, only one big-budget local movie went through with a release in spring 2021. Seobok - a futuristic action film about the world's first human clone who develops special powers, but escapes from his research team - boasted considerable star power in its male leads Gong Yoo and Park Bo-gum, as well as ambitious special effects. It was released on April 15, which is not usually a strong season for moviegoing, but CJ hedged its bets by opening it simultaneously on its own OTT platform TVing. It's not clear how many viewers tuned in to watch Seobok at home, but in theaters at least, the returns were low with 385,000 ticket sales.

Ultimately, not a single Korean release from the first five months of 2021 managed to sell as much as 500,000 tickets. Given that as recently as 2019, a Korean film (Extreme Job) had sold upwards of 16 million tickets, this was quite a shock to the industry.

At the writing of this essay, the local film industry is looking ahead to the 2021 summer season with many of the same feelings and concerns as they had in the previous year. There are some positive signs. South Korea's vaccination drive started later than in many other countries, but when large shipments of vaccines finally began to arrive in May and June, it progressed quickly, with little anti-vaccine sentiment among the populace. Late spring also ushered in the return of high-profile Hollywood releases. Whereas in previous years, local distributors often viewed Hollywood as a competitor, in 2021 they hope that Hollywood can help coax local viewers to re-start their moviegoing habits. Early returns were decent: Fast & Furious 9 passed the 2 million admissions mark to become the highest grossing film of the year to date.

But the question of whether summer 2021 will be a time of recovery for the Korean box office, or yet another disappointment, is still up in the air. The local film industry, which has been pushed to its limits during the pandemic, and which has a large backlog of films waiting for release, has much riding on the outcome.

Between Two Earthquakes: Korean Cinema in 2019

In the year since the previous Far East Film Festival was held in April 2019, two earthquakes have shaken the South Korean film industry. The first was Bong Joon Ho's Parasite, which on multiple levels ranks as the most successful Korean film in history. Its storybook trajectory, which began with a Palme d'Or in May 2019 and ended with its Best Picture win at the Oscars in February 2020, was so unprecedented that the industry was pushed to rethink some of its most basic assumptions about what Korean films can achieve in the global market. With an estimated $257 million worldwide box-office total, including $53 million in U.S. theaters, it is not only the most acclaimed and awarded Korean film of all time, but also the highest grossing.

The second earthquake, of course, was the COVID-19 pandemic, which hit South Korea's film industry just as hard as it did everywhere else. The fact that the country had previously had such a vibrant theatrical market - with Koreans watching more films in theaters per capita than in any other country in the world - meant that the whiplash from postponed releases and closed theaters was especially severe. At this point the long-term impact of the pandemic is still impossible to calculate, but it seems likely that the economics of filmmaking in Korea are going to change in fundamental ways.

The second earthquake, of course, was the COVID-19 pandemic, which hit South Korea's film industry just as hard as it did everywhere else. The fact that the country had previously had such a vibrant theatrical market - with Koreans watching more films in theaters per capita than in any other country in the world - meant that the whiplash from postponed releases and closed theaters was especially severe. At this point the long-term impact of the pandemic is still impossible to calculate, but it seems likely that the economics of filmmaking in Korea are going to change in fundamental ways.

In future times when people look back on the years 2019-2020, memories will be dominated by these two seismic events. But there are other films that emerged in the past 12 months that are in themselves still worth seeking out and remembering. This year's online edition of the Far East Film Festival will serve as an opportunity to highlight some of those works.

Let's start by going back to the summer of 2019. The year to date had produced two huge hits of over 10 million admissions (comedy Extreme Job, released in January and invited to the 21st FEFF in April, and Parasite), but no other commercial standouts. As usual, Korea's major distributors had lined up several ambitious releases for the peak summer season, but given the weak performance of big-budget films in the previous year, their success was far from certain. Sure enough, of the four major releases, two were major commercial disappointments, one just barely broke even and one was a strong success. The disappointments included The King's Letters, a period drama about Korea's most famous monarch King Sejong, which was hammered by an SNS-fueled controversy over the supposed liberties the film took with the historical record; and director Kim Joo-hwan (Midnight Runners)'s big-budget exorcist thriller The Divine Fury, which failed to generate positive word-of-mouth despite the casting of popular star Park Seo-joon. Nationalist-tinged The Great Battle: Roar to Victory, about Korean independence fighters' successful ambush of Japanese colonial forces in June 1920, fared somewhat better with 4.7 million admissions. But it was the disaster movie Exit that ultimately prevailed, with 9.4 million admissions.

Exit, by debut director Lee Sang-geun, imagines a terrorist incident in which poison gas spreads across downtown Daegu, forcing citizens to flee to the top of buildings for safety. The film's effective mixture of likable characters, humor and suspenseful climbing sequences provided the kind of breezy fun many viewers were looking for in the summer months. Produced by Ryoo Seung-wan and his wife Kang Hye-jeong, the film succeeded not with the familiar formula of top-level star power and expensive special effects (one of the benefits of having poison gas as the main antagonist is that it's fairly simple to render visually), but with good storytelling and well-shot suspense.

Exit, by debut director Lee Sang-geun, imagines a terrorist incident in which poison gas spreads across downtown Daegu, forcing citizens to flee to the top of buildings for safety. The film's effective mixture of likable characters, humor and suspenseful climbing sequences provided the kind of breezy fun many viewers were looking for in the summer months. Produced by Ryoo Seung-wan and his wife Kang Hye-jeong, the film succeeded not with the familiar formula of top-level star power and expensive special effects (one of the benefits of having poison gas as the main antagonist is that it's fairly simple to render visually), but with good storytelling and well-shot suspense.

As is often the case, the fall season provided an opening for a mixture of lower-budget genre films and dramas that touch on various aspects of contemporary Korean society. One noteworthy release that outperformed expectations was the hard-edged romantic comedy Crazy Romance, by debut director Kim Han-kyul. Starring Kim Rae-won (The Prison) and the always-delightful Gong Hyo-jin (Door Lock), the film centers around two coworkers, each with a bit of a drinking problem, who enter into a sometimes-friendship, sometimes-flirtation that is never really sure where it is going. Director Kim's sardonic take on Korea's work and social scene, and her refusal to idealize romance, make for a wholly unique film that is difficult to characterize.

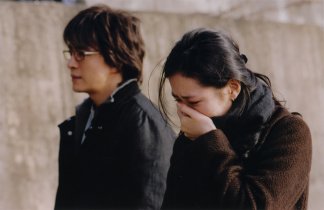

The most discussed release of the fall was the story of an ordinary housewife, Kim Ji-young, Born 1982. The film is based on a 2016 novel by Cho Nam-joo that was a bestseller not only in South Korea, but also in Japan and China (it was subsequently released in English translation in early 2020). The ordinariness of the protagonist is part of the author's point - she chose the name Kim Ji-young because it is the most common female name of her generation, and the characterization is left deliberately abstract. In this way her struggles to get by in a male-dominated society take on a wider resonance. Though not an easy novel to adapt into a film, director Kim Do-young's casting of Jung Yoo-mi in the lead role was inspired, and its release sparked a nationwide discussion about (or in some quarters, an angry backlash against) feminism in contemporary Korea. The film ended up with a solid 3.7 million admissions.

The most discussed release of the fall was the story of an ordinary housewife, Kim Ji-young, Born 1982. The film is based on a 2016 novel by Cho Nam-joo that was a bestseller not only in South Korea, but also in Japan and China (it was subsequently released in English translation in early 2020). The ordinariness of the protagonist is part of the author's point - she chose the name Kim Ji-young because it is the most common female name of her generation, and the characterization is left deliberately abstract. In this way her struggles to get by in a male-dominated society take on a wider resonance. Though not an easy novel to adapt into a film, director Kim Do-young's casting of Jung Yoo-mi in the lead role was inspired, and its release sparked a nationwide discussion about (or in some quarters, an angry backlash against) feminism in contemporary Korea. The film ended up with a solid 3.7 million admissions.

The second half of 2019 was also a comparatively fertile period for Korean independent films. Whereas in recent times it has been mostly politically-oriented documentaries that captured mainstream attention among the 100+ independent films released in theaters each year, in 2019 it was female-centered dramas that received the spotlight. Coming-of-age story House of Hummingbird, set in Seoul in 1994, was far and away the most acclaimed, selling over 130,000 tickets and winning upwards of 50 awards from festivals and awards ceremonies in Korea and abroad. But there were other success stories as well. Director Yoon Ga-eun's The House of Us, a heartfelt companion piece to her acclaimed 2017 feature The World of Us, focuses on a middle-school student trying to save her parents' marriage, and two younger girls she meets who are trying to save their home. Moonlit Winter, the second feature by Director Lim Dae-hyung (Merry Christmas Mr. Mo), takes place mostly in Japan and depicts a long-lost romance between two women. Strong word-of-mouth led the film to over 100,000 admissions. Even the coolly experimental Maggie, which premiered at the 2018 Busan International Film Festival and which departs from many storytelling conventions, managed to attract 40,000 admissions, a strong score for an independent release. It does seem that within the realm of independent cinema, one film's success often paves the way for increased audience interest in subsequent releases as well.

Moving towards the lucrative winter vacation season, the big studios lined up three major releases for mid-late December. Forbidden Dream by veteran director Hur Jin-ho (The Last Princess) also centered around the famous King Sejong, this time on his friendship with noted inventor Jang Young-sil. The chemistry between actors Han Suk-kyu and Choi Min-sik drew the praise of critics but only a modest gross of about 1 million admissions. Comedy Start-Up, based on a famous webtoon and featuring prolific star Ma Dong-seok, fared somewhat better with a gross of 3.3 million. Like Exit, this film too came from Kang Hye-jeong and Ryoo Seung-wan's production house Filmmakers R&K.

But in terms of scale, budget and ultimate commercial success, the behemoth of the winter was the disaster movie Ashfall. Featuring top stars Lee Byung-hun, Ha Jung-woo, Ma Dong-seok, Han Hye-jin and K-pop singer-turned-actress Bae Suzy, the film posits a multiple-stage violent eruption of the volcano Mt. Baekdu which lies on the border between North Korea and China. With all the peninsula threatened with catastrophe, and the North Korean leadership all wiped out in an earthquake, it falls into the hands of a South Korean special forces operative and a North Korean spy to prevent total devastation. Guided by the principle "more is more", the film's ceaseless escalation of spectacle, destruction and sensational plot twists set it on another level from ordinary Korean blockbusters.

But in terms of scale, budget and ultimate commercial success, the behemoth of the winter was the disaster movie Ashfall. Featuring top stars Lee Byung-hun, Ha Jung-woo, Ma Dong-seok, Han Hye-jin and K-pop singer-turned-actress Bae Suzy, the film posits a multiple-stage violent eruption of the volcano Mt. Baekdu which lies on the border between North Korea and China. With all the peninsula threatened with catastrophe, and the North Korean leadership all wiped out in an earthquake, it falls into the hands of a South Korean special forces operative and a North Korean spy to prevent total devastation. Guided by the principle "more is more", the film's ceaseless escalation of spectacle, destruction and sensational plot twists set it on another level from ordinary Korean blockbusters.

The first part of 2020 also opened on a commercially strong note. Around the time Parasite was collecting its four Oscar trophies, the 1970s-set political thriller The Man Standing Next was well on its way to amassing a 4.8 million admissions gross. From the director of Inside Men and The Drug King, the film is based on the real-life assassination of authoritarian president Park Chung-hee in 1979 by the head of his intelligence agency (played by Lee Byung-hun). This is a topic that has been covered multiple times in Korean cinema, such as in Im Sang-soo's controversial The President's Last Bang (2005) - which also screens in this year's FEFF program. The Man Standing Next focuses on the 40 days leading up to the shooting, and the various power struggles and intrigue that caused the protagonist to ultimately pull the trigger. It forms a particularly interesting companion piece with The President's Last Bang, which takes place over 24 hours but which nonetheless shows considerable overlap with the new film. The strong box office success of The Man Standing Next suggests that contemporary Korean history, which has formed the basis for many a blockbuster in the past two decades, continues to have commercial appeal if packaged in the right way.

Nonetheless, trouble was brewing for Korean films. South Korea's first case of COVID-19 was reported on January 20, and anxiety spread quickly among the local populace, who still remembered a poorly-handled outbreak of the MERS coronavirus in 2015. Film distributors fell into a quandary about how to respond. One of the first casualties was the critically-praised thriller Beasts Clawing at Straws, which had just won a Special Jury Award at Rotterdam the previous month, and which was scheduled to open in theaters on February 12. Featuring a complex, well-structured plot and strong performances from Jung Woo-sung and Jeon Do-yeon, the film looked like a release with strong commercial potential. But as frightening headlines about the novel coronavirus began to proliferate, distributor Megabox Plus M decided to move the release back a week, to February 19. In retrospect, this was a fatal mistake, as a major cluster of infections were reported in Daegu on the 19th. The news worsened quickly and within a week, South Korea had one of the highest concentrations of confirmed infections in the world. Beasts Clawing at Straws would end up with only 630,000 admissions, the first of many titles to see their shot at profitability go up in smoke.

Nonetheless, trouble was brewing for Korean films. South Korea's first case of COVID-19 was reported on January 20, and anxiety spread quickly among the local populace, who still remembered a poorly-handled outbreak of the MERS coronavirus in 2015. Film distributors fell into a quandary about how to respond. One of the first casualties was the critically-praised thriller Beasts Clawing at Straws, which had just won a Special Jury Award at Rotterdam the previous month, and which was scheduled to open in theaters on February 12. Featuring a complex, well-structured plot and strong performances from Jung Woo-sung and Jeon Do-yeon, the film looked like a release with strong commercial potential. But as frightening headlines about the novel coronavirus began to proliferate, distributor Megabox Plus M decided to move the release back a week, to February 19. In retrospect, this was a fatal mistake, as a major cluster of infections were reported in Daegu on the 19th. The news worsened quickly and within a week, South Korea had one of the highest concentrations of confirmed infections in the world. Beasts Clawing at Straws would end up with only 630,000 admissions, the first of many titles to see their shot at profitability go up in smoke.

The pandemic also affected films in production. In a case of spectacularly bad timing, a string of big-budget films set in overseas locations were all scheduled to ramp up production in early 2020. Of these, only Ryoo Seung-wan's Escape From Mogadishu, which began shooting in Morocco in late 2019, managed to wrap production before international travel restrictions were put in place. Productions that were not so lucky included the crime drama Bogota, which pulled out of Colombia with only a fraction of its shooting complete; Yim Soon-rye's Afghanistan-set Negotiation, which had to cancel its planned shoot in Jordan; and the Lebanon-set kidnapping drama Pirap starring Ha Jung-woo which had to postpone its production to 2021.

South Korea did end up handling its outbreak well and flattening its curve, so that the country never went into full lockdown. But theaters were hit particularly hard, and film attendance slowed to a trickle. Virtually all of the major commercial releases were postponed to later in the year, with re-releases like La La Land taking up the slack. Nonetheless there were a few low-budget independent films that pushed ahead with their releases, and ended up grossing numbers that - by the standards of independent cinema -- were rather decent. One notable example was Lucky Chan-sil, the offbeat story of an out-of-work producer, which was enthusiastically received during its premiere at the 2019 Busan International Film Festival. Opening commercially on March 5, the film still managed to pull in 25,000 viewers, which would have been considered a success in any year.

South Korea did end up handling its outbreak well and flattening its curve, so that the country never went into full lockdown. But theaters were hit particularly hard, and film attendance slowed to a trickle. Virtually all of the major commercial releases were postponed to later in the year, with re-releases like La La Land taking up the slack. Nonetheless there were a few low-budget independent films that pushed ahead with their releases, and ended up grossing numbers that - by the standards of independent cinema -- were rather decent. One notable example was Lucky Chan-sil, the offbeat story of an out-of-work producer, which was enthusiastically received during its premiere at the 2019 Busan International Film Festival. Opening commercially on March 5, the film still managed to pull in 25,000 viewers, which would have been considered a success in any year.

Looking ahead to the future, it's hard to see what lies in wait. For all the struggles that Korean independent cinema has been through in recent years, this sector will likely show more resilience in the face of the damage wrought by the pandemic. But it's an open question when audiences will return to theaters in numbers that will support a big-budget film. New labor regulations in recent years have pushed up the cost of shooting in Korea, so at the very least it will be a struggle to get back to making movies on the scale of Ashfall. On the other hand, the success of Parasite suggests that if or when the world does recover from the pandemic, be it in 2021 or in later years, South Korea may be poised to continue its a role as an influential cultural leader far beyond its own borders. Clearly, hard times lie ahead. But all hope is not lost.

Sending a Message: Korean Cinema in 2018

There are times in the history of any film industry when the audience makes its feelings known. The past twelve months have been such a time. A string of big-budget, high profile releases that were expected to do well were rejected by the audience with a vehemence that was a bit startling. Online discourse about film, which has always been polarized, displayed a sustained level of anger and frustration that was noticeable. On the other hand, films that offered something new, or were made in a style or genre that had been overlooked in recent years, often outperformed expectations. When you step back and look at the year as a whole, there was a noticeable gap between the kind of films that Korea's big studios were releasing in theaters, and the kind of films that audiences wanted to see. After losing an astonishing amount of money, the film companies now seem to have gotten the message.

Consider as an example The Drug King, a big-budget production released in December 2018. On paper this project must have seemed like a can't-miss prospect. The director Woo Min-ho was coming off a massive, well-received hit film Inside Men (2015). Leading star Song Kang-ho has a long, reliable track record of success, most recently in the massive 2017 hit A Taxi Driver, and can be relied upon to give a dynamic, eye-opening performance. He was surrounded by a strong supporting cast including Bae Doona and Jo Jeong-seok. The story is based on real events and references the major social transformations of the late 20th century - an approach that has worked well in the past. Finally, it was released by major distributor Showbox during the peak winter box office season, when students finish their exams and head to the movie theaters in droves.

Consider as an example The Drug King, a big-budget production released in December 2018. On paper this project must have seemed like a can't-miss prospect. The director Woo Min-ho was coming off a massive, well-received hit film Inside Men (2015). Leading star Song Kang-ho has a long, reliable track record of success, most recently in the massive 2017 hit A Taxi Driver, and can be relied upon to give a dynamic, eye-opening performance. He was surrounded by a strong supporting cast including Bae Doona and Jo Jeong-seok. The story is based on real events and references the major social transformations of the late 20th century - an approach that has worked well in the past. Finally, it was released by major distributor Showbox during the peak winter box office season, when students finish their exams and head to the movie theaters in droves.

Yet The Drug King performed at only a fraction of its high expectations (1.8 million admissions, which was well below its break-even point). Online comments about the film were merciless, condemning the predictable rise-and-fall plot and the film's reliance on provocative content to attract attention. Within no time it was being held up as an example of all that is wrong with contemporary Korean cinema. Although it's true that The Drug King compares poorly to Inside Men in terms of storytelling and execution, it seems likely that if it had been released five years earlier, it wouldn't have received anywhere near the same level of criticism. In other words, much of the anger directed towards The Drug King may have reflected accumulated frustration about Korean films in general.

In contrast, consider the case of the mid-budget comedy Extreme Job. From up-and-coming director Lee Byoung-heon, one of the few directors working in the film industry to specialize in comedy, the film is about a group of detectives who struggle to keep a low profile while on an extended stakeout of a criminal organization. They decide to buy out a failing fried chicken restaurant across the street from the criminal's hideout to give them a base, secure in the knowledge that hardly any customers will show up. But when a lone customer starts raving online about a bizarre fusion fried chicken dish cooked up by one of the cops, the restaurant becomes a viral sensation and they are soon overwhelmed with business.

In this case, a very different dynamic was at work. The film is undeniably funny and effectively paced. Given the audience's positive response, it's no surprise that it turned into a hit. But the scale of its success went far beyond even the rosiest projections. Released in late January 2019, Extreme Job spent a month at #1 and recorded an astonishing 16.3 million admissions, making it Korea's second most popular film of all time after 2014 historical epic Roaring Currents' total of 17.6 million admissions. In terms of revenue, Extreme Job ranks at the top with US$123 million. Director Lee surely deserves all the credit for his success, but it's also true that the film seemed to tap into pent-up demand for a decent comedy.

In this case, a very different dynamic was at work. The film is undeniably funny and effectively paced. Given the audience's positive response, it's no surprise that it turned into a hit. But the scale of its success went far beyond even the rosiest projections. Released in late January 2019, Extreme Job spent a month at #1 and recorded an astonishing 16.3 million admissions, making it Korea's second most popular film of all time after 2014 historical epic Roaring Currents' total of 17.6 million admissions. In terms of revenue, Extreme Job ranks at the top with US$123 million. Director Lee surely deserves all the credit for his success, but it's also true that the film seemed to tap into pent-up demand for a decent comedy.

Why have so few Korean comedies been made in recent years? For the most part, it's because of conventional wisdom among investors and the big film studios. Comedies have been considered an "old" genre, that worked well in the early 2000s but were not well suited to the contemporary audience. Now, of course, that conventional wisdom has been shattered, and film companies are rushing to add comedies to their slate.

But it goes beyond a simple question of genre. There is a sort of money-making template, based on star power, high production values and serious, weighty themes, that has been embraced by investors. The idea that the middle is falling out of the industry, leaving only low budget films and blockbuster-scale works that can secure a wide release, has been repeated like a mantra, even in the face of contradictory evidence. As a result of these beliefs (and rising production costs, particularly due to new labor rules), 2018 saw a massive increase in the number of big-budget films (defined as 10 billion won or US$9 million and up), and comparatively low levels of mid-budgeted films in the $3 million to $7 million range.

In the end, the big-budget films suffered a bloodbath, and the few mid-budgeted films that were released did rather well. Many of the blockbuster flops were from directors who have solid track records of box office success, such as Kim Jee-woon's dystopian Illang: The Wolf Brigade (pictured right), Kang Hyeong-cheol's musical Swing Kids set in a POW camp, Kim Byung-woo's military thriller Take Point, Choo Chang-min's murder mystery Seven Years of Night, Yeon Sang-ho's Psychokinesis, Woo Min-ho's The Drug King, and from early 2019, Lee Jeong-beom's corrupt cop drama Jo Pil-ho: The Burning Rage.

In the end, the big-budget films suffered a bloodbath, and the few mid-budgeted films that were released did rather well. Many of the blockbuster flops were from directors who have solid track records of box office success, such as Kim Jee-woon's dystopian Illang: The Wolf Brigade (pictured right), Kang Hyeong-cheol's musical Swing Kids set in a POW camp, Kim Byung-woo's military thriller Take Point, Choo Chang-min's murder mystery Seven Years of Night, Yeon Sang-ho's Psychokinesis, Woo Min-ho's The Drug King, and from early 2019, Lee Jeong-beom's corrupt cop drama Jo Pil-ho: The Burning Rage.

Each of these films had a defensible strategy for finding box-office success, but part of the problem was that they all had more or less the same strategy. There is clearly a level of audience fatigue setting in for the sort of dark, heavy drama that characterizes much recent big-budget filmmaking. One recent blockbuster-scale release (which I won't identify for the sake of spoilers) ends with the film's charismatic leads being gunned down by machine gun fire. This was meant to reference Korea's tragic modern history, and perhaps provoke an upsurge of nationalist feeling, but after years of watching such films, viewers no longer seem to be in the mood. The idea that blockbuster films should be fun to watch is something that has been overlooked in recent times.

A look at the blockbusters that did achieve some blockbuster success is illuminating. 2018's most successful film by far was Along With the Gods: The Last 49 Days which tallied 12.3 million admissions in early August. This sequel to the even more successful Along With the Gods: The Two Worlds from late 2017 is based on a popular web comic, and features a mix of spectacle and melodrama set in the realm of the afterlife. Despite a weak critical reception, the film appealed to all age groups and set itself up for more lucrative sequels in the future.

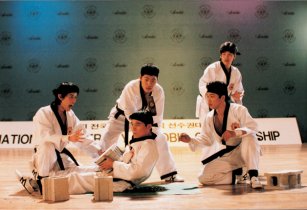

Another commercial success, if not on the same level, was director Kim Kwang-sik's first big budget production The Great Battle. Budgeted at US$20 million and based on a 7th century skirmish between Tang Dynasty forces and the residents of the small Ansi Fortress, the film is rich in spectacle and features a charismatic performance by popular star Jo In-sung. Although not groundbreaking, it benefits from effective pacing and an emotionally involving buildup to the final confrontation. It was, in other words, fun -- and audiences lined up to make it the second-highest grossing Korean film of the year, with a total of 5.4 million admissions.

Another commercial success, if not on the same level, was director Kim Kwang-sik's first big budget production The Great Battle. Budgeted at US$20 million and based on a 7th century skirmish between Tang Dynasty forces and the residents of the small Ansi Fortress, the film is rich in spectacle and features a charismatic performance by popular star Jo In-sung. Although not groundbreaking, it benefits from effective pacing and an emotionally involving buildup to the final confrontation. It was, in other words, fun -- and audiences lined up to make it the second-highest grossing Korean film of the year, with a total of 5.4 million admissions.

Two other big-budget films managed to do respectably well, earning positive word of mouth through effective characterization and storytelling, as well as highly memorable settings and content. The Spy Gone North premiered at Cannes in May 2018 and went on to earn a respectable 4.9 million admissions during its summer release. Set in the 1990s, and based on the dramatic real-life experiences of an undercover spy, the US$20 million film presented a new perspective on North-South relations as well as some beautifully rendered shots of Pyongyang.

Meanwhile Lee Hae-young's Believer, a loosely adapted remake of Johnnie To's Drug War, was the one big-budget release of 2018 that seemed to pick up real momentum from positive word of mouth. With a supremely talented ensemble cast giving highly memorable performances, the film demonstrated that not all dark-themed films were doomed to fail, if they exhibited tight storytelling and something unique. Despite being released "off season" in May, Believer accumulated just over 5 million admissions.

The picture was much brighter for the mid-budgeted films of 2018, which appealed to viewers mostly on the strength of their storytelling. At the head of the pack was Intimate Strangers (pictured), the Korean remake of the famously successful 2016 Italian feature Perfect Strangers which has spawned numerous remakes across the world. Sticking fairly close to the original, the film benefitted from good casting and enthusiastic word of mouth to rack up a highly impressive 5.3 million admissions. Considering its modest budget, it stands as one of the year's most profitable releases.

The picture was much brighter for the mid-budgeted films of 2018, which appealed to viewers mostly on the strength of their storytelling. At the head of the pack was Intimate Strangers (pictured), the Korean remake of the famously successful 2016 Italian feature Perfect Strangers which has spawned numerous remakes across the world. Sticking fairly close to the original, the film benefitted from good casting and enthusiastic word of mouth to rack up a highly impressive 5.3 million admissions. Considering its modest budget, it stands as one of the year's most profitable releases.

Also drawing attention was Default, the second film by director Choi Kook-hee (Split), which examines South Korea's questionable handling of the 1997 Asian financial crisis, and its closed door dealings with the International Monetary Fund over a record bailout package. Sharing some things in common with Hollywood film The Big Short, but also portraying the lasting effects of the crisis on South Korea's middle class, the film is especially powered by a standout performance by actress Kim Hye-soo.

In terms of genre cinema, director Lee Kwon's well-received thriller Door Lock was also built around the acting skills of an acclaimed performer. Kong Hyo-jin plays an employee at a bank who suspects that someone is trying to get into her apartment. A remake of the 2011 Spanish thriller Sleep Tight by Jaume Balaguero, the film's expert handling of suspense was well received by audiences. Meanwhile the popular Ma Dong-seok of Train to Busan fame also found a suitable vehicle for his star persona in Unstoppable, a hugely likeable and entertaining action film that recalls the Taken franchise.

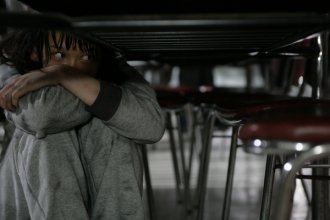

Although the early part of 2019 has been dominated by Extreme Job's extreme success, a few other works have garnered attention from audiences. Innocent Witness (pictured) is a courtroom drama about an autistic girl (Kim Hyang-gi) who is the only witness of a mysterious crime. When the defendant's lawyer (Jung Woo-sung, in a charismatic performance) comes looking for a way to discredit her testimony, he finds himself turning more sympathetic to her point of view.

Although the early part of 2019 has been dominated by Extreme Job's extreme success, a few other works have garnered attention from audiences. Innocent Witness (pictured) is a courtroom drama about an autistic girl (Kim Hyang-gi) who is the only witness of a mysterious crime. When the defendant's lawyer (Jung Woo-sung, in a charismatic performance) comes looking for a way to discredit her testimony, he finds himself turning more sympathetic to her point of view.

Finally, the drama Birthday holds a special place among recent films. It's hard to overestimate the effect of the tragic 2014 sinking of the Sewol Ferry on contemporary Korean society. Although the politics surrounding the event are complicated, Birthday avoids politics and depicts a family torn apart by the loss of their teenage son. Centered around the heartbreaking performances of award-winning actors Sol Kyung-gu and Jeon Do-yeon, the film has proven to be both meaningful and well made. It also marks the emergence of an exciting new talent in debut director Lee Jong-eon, a longtime assistant to director Lee Chang-dong.

So where does Korean cinema stand at the current moment? Although the overall statistics for 2018 indicate only a modest decline, the large number of dramatic box office failures suggest that producers and investors have some soul-searching to do. The last decade has seen the increasing systemization of the film industry, as its biggest companies have grown ever more powerful. In some respects this has made the industry stronger, but it has also left it vulnerable in a creative sense. The more formulas and templates adopted by the big studios, the more likely it is that audiences will grow tired of seeing the same style of movies over and over again.

It may be that someday we can look back on 2018 as a key moment, when the audience spoke up and expressed its dissatisfaction with the state of Korean filmmaking. At first glance it looks like the studios are getting the message, but whether they are truly flexible enough to respond to audiences' evolving tastes is yet to be seen.

Making Amends: South Korean Cinema in 2017

The past 12 months have brought a change of seasons to South Korean politics and society. For the Korean film community, the election of President Moon Jae-in to replace the disgraced and impeached Park Geun-hye signaled the end of a decade-long winter, which was marked by slashed funding, government reprisals and secret blacklists of cultural figures. Much of the focus of the past year has been on rebuilding institutions like the Korean Film Council and the Busan International Film Festival which had been compromised under the previous two administrations. But the arrival of spring has not been without its own degree of turbulence. In the political sphere, tensions with North Korea and the U.S. has kept the country on edge, even as a new diplomatic front opened in early 2018. And after a slow start, the #MeToo movement hit South Korea with full force, shaking many sectors of society, including the film industry.

Several films released over the past year have successfully captured various aspects of the current historical moment. The sense of society rising up and ushering in a new era was effectively depicted in Jang Joon-hwan's 1987: When the Day Comes. Set in the run-up to the so-called June Struggle of 1987, in which mass demonstrations forced the military government to introduce direct presidential elections and a democratic constitution, the film follows a wide cast of characters in order to show how one small act of resistance can lead to another, and gradually build up momentum for social change. With its combination of a timely social message (the film inevitably calls to mind the mass demonstrations against the government leadership in 2016-17), its complex but effective storytelling, and its all-star cast, 1987: When the Day Comes was for many critics the film of the year.

Several films released over the past year have successfully captured various aspects of the current historical moment. The sense of society rising up and ushering in a new era was effectively depicted in Jang Joon-hwan's 1987: When the Day Comes. Set in the run-up to the so-called June Struggle of 1987, in which mass demonstrations forced the military government to introduce direct presidential elections and a democratic constitution, the film follows a wide cast of characters in order to show how one small act of resistance can lead to another, and gradually build up momentum for social change. With its combination of a timely social message (the film inevitably calls to mind the mass demonstrations against the government leadership in 2016-17), its complex but effective storytelling, and its all-star cast, 1987: When the Day Comes was for many critics the film of the year.

Just as timely in many ways was the political thriller Steel Rain, which explores the present-day tension between South and North Korea. Directed by Yang Woo-seok (whose debut film The Attorney was an FEFF award-winner in 2014), the film opens with a elaborately-planned coup attempt against the North Korean leadership. In the chaos and confusion that results, a North Korean military agent ends up in Seoul, forced to cooperate with a South Korean national security secretary whose motives he cannot trust. At turns suspenseful, funny, frightening and thought-provoking, the film opened in December at a time when real-life nuclear tensions on the Korean peninsula were almost as intense as the events depicted in the film.

The abovementioned movies represent two of the three major releases of the 2017-18 winter box-office season. As it turned out, the third film Along With The Gods: The Two Worlds also (unintentionally) found itself at the center of a major social storm. The #MeToo movement, which took shape last fall in Hollywood following allegations against producer Harvey Weinstein, did not immediately take hold in Korea. However in late January, a female prosecutor Seo Ji-hyun appeared on live TV to describe being groped at a funeral by one of her superiors, and the reprisals she suffered after she tried to speak up about it. The outpouring of public support she received encouraged other women to go public with their own stories, and before long the #MeToo movement had penetrated deep into all corners of Korean society.

Within the film industry, one of the first figures to be accused was the popular supporting actor Oh Dal-soo (Assassination, Ode to My Father), who admitted to sexually abusing several women early in his career. Oh had played a key supporting role in the tremendously successful Along With the Gods: The Two Worlds, although the film had already earned the majority of its 14.4 million admissions (the second-highest grossing film of all time in Korea) at the time the story broke. Nonetheless, this film is merely the first in a two-part series, with part two already shot and being readied for a summer 2018 release. After some deliberation, the production company decided to re-cast and re-shoot the scenes that feature Oh and another actor Choi Il-hwa who was accused of similar crimes.

Within the film industry, one of the first figures to be accused was the popular supporting actor Oh Dal-soo (Assassination, Ode to My Father), who admitted to sexually abusing several women early in his career. Oh had played a key supporting role in the tremendously successful Along With the Gods: The Two Worlds, although the film had already earned the majority of its 14.4 million admissions (the second-highest grossing film of all time in Korea) at the time the story broke. Nonetheless, this film is merely the first in a two-part series, with part two already shot and being readied for a summer 2018 release. After some deliberation, the production company decided to re-cast and re-shoot the scenes that feature Oh and another actor Choi Il-hwa who was accused of similar crimes.

Major figures in the political world, academia, literature, theater circles and more have been brought down by #MeToo allegations, but the most high profile case in the film industry involves Golden Lion-winner Kim Ki-duk and his frequent collaborator Cho Jae-hyun, who were accused by multiple women on a leading investigative TV program of repeated assault. Both are now currently under criminal investigation, and it appears that their long careers may be over.

So in one sense, the Korean film industry is going through a period of profound upheaval and change. The Korean Film Council is making an effort to address issues like sexual harassment and gender discrimination in the industry. At the same time, they are also drawing up plans to increase support for independent cinema, which has suffered through a lean decade under conservative rule. The number of independent films produced in Korea is expected to rise in the coming years, as more funds are made available for production support. Nonetheless, distribution and marketing of independent films will remain a challenge in a market dominated by the major distributors.

The one area of the industry that has not shown much change is in the overall statistics. In 2017 there were 219.9 million film tickets sold totaling $1.66 billion, a 0.8% increase on the previous year. The market share of Korean films dropped slightly to 51.8%. Four distributors - CJ Entertainment, Lotte Entertainment, Showbox, and NEW - continue to dominate the market (CJ has been the top distributor for 15 years straight), although the smaller distributor-exhibitor Megabox found considerable success with mid-budget releases like The Outlaws, Little Forest and Anarchist from the Colony.

Some of the year's box-office hits were expected to do well from the start, while others came as a surprise. The most ambitious, high-profile release of 2018 was Ryoo Seung-wan's big-budget The Battleship Island, which opened in July. Set during World War II on the Hashima Island coal mine, the film depicts the tragic experiences of Korean forced laborers and women forced into prostitution. Its jaw-dropping action sequences and massive open set unquestionably set a new standard for Korean blockbusters. Nonetheless the film's mix of historical polemic and genre spectacle proved highly controversial, in a way that exposed divisions within Korean society. Those on the more nationalist end of the spectrum were incensed at the film's depiction of Koreans collaborating with the Japanese, while those on the other end of the spectrum accused the film itself of being nationalist. In the end, The Battleship Island amassed 6.6 million admissions - a considerable amount, but far short of initial expectations.

Some of the year's box-office hits were expected to do well from the start, while others came as a surprise. The most ambitious, high-profile release of 2018 was Ryoo Seung-wan's big-budget The Battleship Island, which opened in July. Set during World War II on the Hashima Island coal mine, the film depicts the tragic experiences of Korean forced laborers and women forced into prostitution. Its jaw-dropping action sequences and massive open set unquestionably set a new standard for Korean blockbusters. Nonetheless the film's mix of historical polemic and genre spectacle proved highly controversial, in a way that exposed divisions within Korean society. Those on the more nationalist end of the spectrum were incensed at the film's depiction of Koreans collaborating with the Japanese, while those on the other end of the spectrum accused the film itself of being nationalist. In the end, The Battleship Island amassed 6.6 million admissions - a considerable amount, but far short of initial expectations.

Another major summer release, Jang Hun's A Taxi Driver, also took its inspiration from a real-life tragedy. In this case it was a lethal government crackdown on demonstrators in the city of Gwangju in 1980, which ended with hundreds (or perhaps thousands) of people killed and the army invading the city. The film focuses on a German photojournalist Jürgen Hinzpeter who, with the help of a taxi driver from Seoul, recorded images from the events in Gwangju and then distributed them to the outside world. Since news of the incident was suppressed in the Korean press, underground videotapes of the footage shot by Hinzpeter circulated among the Korean populace in the coming years - as indeed can be seen in a memorable scene from 1987: When the Day Comes. A Taxi Driver proved to be the must-see release of the summer season, with 12.2 million tickets sold.

Some other hits from 2017 arrived with less pre-release hype, but succeeded through strong word of mouth. Midnight Runners by up-and-coming director Jason Kim tells the story of two young police academy students who witness a kidnapping late one night, and decide to pursue the kidnappers, despite their lack of experience. A funny and warm-hearted action comedy that also goes into some pretty dark places, the film hung on to amass an impressive 5.7 million admissions.

The Outlaws by debut director Kang Yun-sung was even more of a surprise. A violent thriller about an ethnic Korean gangster from China, and the police detective who tries to bring him to justice, the film looked from the outside like any number of other Korean mid-budget crime films. But a combination of inventive characterization, energetic pacing, and a charismatic performance by Ma Dong-seok (a.k.a. Don Lee, Train to Busan) turned it into a potent force at the box office. Indeed, with his unique blend of physical brawn and toughness masking an inner warmth and sympathy, Ma Dong-seok is proving himself to be a major box-office draw. After debuting in early October at #3, The Outlaws quickly rose to #1 and held on long enough to rack up a highly impressive 6.9 million admissions.