Top Ten Lists for the Decade, 2000-2009

TThe years 2000-2009 were a transformative decade for Korean cinema. A large number of important directors became famous in this period, and for the first time Korean films began to travel widely around the world, both at international film festivals and in commercial releases. It has been exciting for all of us to witness this flowering of Korean cinema, but with the decade now ended we are taking the opportunity to look back and identify our own personal standouts and favorites. The critics below represent a range of different perspectives, and each one has been free to choose their own criteria in making their list. We hope this page will give readers a sense of the highlights of the past decade, and to inspire them to search out those titles which they have missed.

Adam Hartzell -- Darcy Paquet -- Davide Cazzaro -- Hong Jiro -- Lance Crayon -- Kyu Hyun Kim

Adam Hartzell

As you'll see from my list, I prefer the slow, contemplative film to the big box office spectaculars. I also am not a fan of the violent film regardless of the moral points it makes amongst the punches, poundings and pulverizing. As for certain directors missing from my list, it's pretty clear that Kim Ki-duk's films have never impressed me, except for Samaritan Girl (2004). And although I enjoy Park Chan-wook's films, his films haven't meant as much for me over the years as they have for so many others. This is a very personal top ten, that's all. I've chosen the films that have had the greatest impact on me over the decade, the films and directors who drew me to South Korean film. Plus, another adjustment I made was to only include one film by any director, basically to avoid this list being inundated with Hong Sangsoo films. My reviews on this page (which Darcy will link to) still speak for my feelings about these films, so I won't write anymore about them. But for those where I didn't write the Koreanfilm.org reviews, I'll provide some brief thoughts...

10. Wanee & Junah (2001), Kim Yong-gyun

10. Wanee & Junah (2001), Kim Yong-gyun

9. Camel(s) (2002), Park Ki-yong -- An affair in stark black and white. Little back story, only conversation and silences giving us context. The rhythm of windshield wipers in the rain still have me thinking of this film.

8. Oasis (2002), Lee Chang-dong -- Two marginalized people given a moment away from the margins. An emotional workout of a film with two stellar acting performances.

7. Host & Guest (2006), Shin Dong-il

6. Grain In Ear (2006), Zhang Lu

5. Sa-Kwa (2005), Kang Yi-kwan

4. Take Care Of My Cat (2001), Jeong Jae-eun -- In my mind, the best film about girls at the edge of adulthood ever made. Can't get enough of that lovely soundtrack too.

3. Invisible Light (2003), Gina Kim

2. Turning Gate (2002), Hong Sangsoo -- I fluctuate between my favorite Hong films being this one or The Power Of Kangwon Province. But this is definitely one of those rare films I can watch over and over again for constant cerebral pleasures.

1. Memories Of Murder (2003), Bong Joon-ho -- Genre filmmaking at its finest. This will truly stand the test of time as one of greatest films (let alone South Korean) ever made.

(Adam Hartzell is a contributing writer for sf360.org, Koreanfilm.org, and Hell on Frisco Bay. He has written essays about South Korean director Hong Sang-soo for GreenCine, the San Francisco Asian American International Film Festival's Retrospective on Hong Sang-soo in 2007, and specifically on Hong's second film The Power of Kangwon Province for The Cinema of Japan and Korea, part of the Walflower Press 24 Frames series on national cinemas.)

Darcy Paquet

Given that this is a look over the past 10 years, I've tried to focus on films that, for whatever reason, have exhibited staying power. These are the works that I and my small circle of Korean film loving friends seem to keep talking about. If you'll forgive a slightly gross metaphor, these are the ones that, after years of being chewed over, still retain their flavor. I've limited myself to one film per director, because it's hard enough to narrow it down as it is...

1. Memories of Murder (2003) -- Every other slot on this list is subject to change, depending on my mood or what I have re-watched recently, but this film has a permanent place at the top. More than anything else I think what most impresses me about this movie is that it is so well-formed and executed, both on the level of tiny details and in the film's overall structure. Every element of this film works, and it all works together.

1. Memories of Murder (2003) -- Every other slot on this list is subject to change, depending on my mood or what I have re-watched recently, but this film has a permanent place at the top. More than anything else I think what most impresses me about this movie is that it is so well-formed and executed, both on the level of tiny details and in the film's overall structure. Every element of this film works, and it all works together.

2. Old Boy (2003) -- In my mind I picture this film as a very heavy object moving at a very great speed (as opposed to Sympathy for Mr. Vengeance (2002), a similarly accomplished film that evokes the image of something very large and heavy, moving at a slow speed). The momentum we feel in the film stems from more than just the narrative, there is a relentless onward motion in the filmmaking itself, and that's not something you see very often.

3. Save the Green Planet! (2003) -- How sad it is that Jang Jun-hwan only made one film in this past decade. He's been referred to as the Mozart of the Korean film industry, but in contrast to music, which you can sit down and write with a piano, pencil and paper, filmmaking requires a lot more support. Let's hope he returns for next decade's list.

4. Secret Sunshine (2007) -- Certainly any of Lee Chang-dong's three films released in this decade (Peppermint Candy opening on January 1, 2000) would be a worthy choice for this list, but if you add in the performance of Jeon Do-yeon then I think the choice becomes more obvious. There is something in the relentlessness of this film that repels me, but at the same time it is impossible to resist.

5. The President's Last Bang (2005) -- There are two things that I love about this film. It brings an almost mythical event in recent Korean history down to a very tactile level; you feel that you are right there, and you can reach out and touch what you see on the screen. And I love the film's very odd second half, when the president is already dead but the story continues to unfold. For me, the film showed how power lies in the system created by one man, and even if you kill the man, the system may live on.

6. Woman on the Beach (2006) -- I've always respected and admired the works of Hong Sang-soo, but it was from this film that I began calling myself a fan. In some ways it marks no major departure from his previous works, but there is a sense of something opening up in his filmic world, like a breeze blowing in from the ocean. It's not that I consider this film to be better than the others, I just like it better.

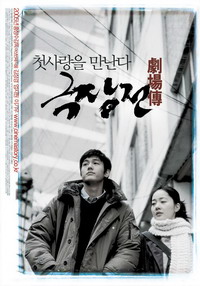

7. One Fine Spring Day (2001) -- Back in 2001 I might have considered several other works from that year to be superior to this one, but nine years later I think this is the one that stands out. It's the kind of melodrama that they only make in Korea, but at the same time it stands out from all other Korean melodramas. The only thing that keeps this film short of perfection is its overuse of music.

8. Paju (2009) -- It hasn't been long since I first watched this film, and so I may not have a proper perspective on it, but this work's complexities and contradictions thrilled me. A coming-of-age story, and much more besides.

9. My Dear Enemy (2008) -- I'm a big fan of this director, and I had a hard time deciding between this film and Ad Lib Night (2006). But even though My Dear Enemy is more mainstream in style, I think it will ultimately leave a greater impact. Great acting, highly sensitive directing,  and the confidence to base a film on so simple a premise: all these combine to make a truly extraordinary work.

and the confidence to base a film on so simple a premise: all these combine to make a truly extraordinary work.

10. (tie) A Tale of Two Sisters (2003) / Someone Special (2004) -- Okay, let me cheat slightly and list a tie for the last slot. Kim Jee-woon has left an unmistakable mark on contemporary Korean cinema, and although on another day I might have chosen A Bittersweet Life, today I'll go with A Tale of Two Sisters, the iconic Korean horror film. Even with its slightly messy ending, it is an achievement. And Jang Jin's Someone Special is my favorite Korean comedy... you can poke holes in it all you like, but the film is unique and it was made with real feeling. May it live long in people's memories.

Other films/directors that almost made the list, in chronological order: Chunhyang (2000), Failan (2001), Nabi (2001), Take Care of My Cat (2001), Repatriation (2004), Pruning the Grapevine (2007), Epitaph (2007), My Friend & His Wife (2008), The Chaser (2008).

It's been an amazing 10 years, no matter how you look at it. Will the next decade be able to compare? It may well be that we are given 10 more films which are the equal of the ones listed above, but the industry as a whole will be unlikely to see such transformative changes as we saw in the early and middle part of the past decade.

Davide Cazzaro

It would be presumptuous of me to say I have prepared a "Top 10"... I probably couldn't have anyway, as in the past two-three years I have not been able to follow Korean cinema as closely as I did before. As a result, I could only pen down something shamelessly subjective and chronologically unbalanced -- thinking carefully, however, isn't expressing preferences something ineluctably subjective and unbalanced?

Listed below, in chronological order, are the works that came to mind first when recollecting this pivotal, roller-coaster decade. Regrettably, only two debut features are included and, even worse, there are no films by women directors... Miahnhamnida.

The Isle (2000) -- Kim Ki-duk

The Isle (2000) -- Kim Ki-duk

Virgin Stripped Bare by Her Bachelors (2000) -- Hong Sang-soo

Oasis (2002) -- Lee Chang-dong

Resurrection of the Little Match Girl (2002) -- Jang Sun-woo

Sympathy for Mr. Vengeance (2002) -- Park Chan-wook

A Good Lawyer's Wife (2003) -- Im Sang-soo

Save the Green Planet! (2003) -- Jang Jun-hwan

Influenza (2004) -- Bong Joon-ho

Repatriation (2004) -- Kim Dong-won

Café Noir (2009) -- Chung Sung-ill

Lastly, let me venture to mention what in many respects could be regarded as the "rediscovery of the decade": Holiday (Lee Man-hee, 1968)

(Davide Cazzaro is an Italian film scholar specializing in East and Southeast Asian cinemas and a PhD candidate at Goldsmiths, University of London. For a number of years now, he has been working as consultant and curator for the Mostra Internazionale del Nuovo Cinema di Pesaro. He co-edited Il cinema sudcoreano contemporaneo e l'opera di Jang Sun-woo.)

Hong Jiro

This is not my "most favorite" list. Of course I like these films and some are definitely my beloved ones, but there could be others I value higher and visit more often. Also, this is not a list of the "best cinematic achievements." I know Memories of Murder or Mother can be said to be more tightly constructed or more beautifully arranged than The Host, for instance. Then what is the criteria? Somehow these films feel like the most unlikely, least possible movies in Korea. I'm not saying they are more "universal" films rather than Korean ones and that they don't evoke any Koreanness. (I chose Chunhyang, right?) However, they shocked me with their attempts to do something (thematically or cinematically) that other coy Korean films fear, avoid, or wouldn't dare to think about. What is more, their efforts succeeded. It's a bit ironical to emphasize "being different from ordinary Korean films" while making a list for Koreanfilm.org, but I believe that's the spirit which make films of this country still worthy of being loved.

Chunhyang (2000) -- Though Chunhyang-jeon may be introduced as the most famous literary classic, that every Korean knows well, it is a different matter whether they love it. Usually it is regarded as a subject of study rather than a beloved classic, and the story seems too outdated for viewers to accept its theme sincerely these days. However, Im Kwon-taek dared to turn this relic into cinematic ecstasy. By his experiments in shooting, editing, and even making actors act alongside pansori, Korean traditional musical performance, the world of Chunhyang revives vividly, and I could finally see the world through her eyes, and of the people who have loved it for hundreds of years.

Sorum (2001) -- For the last two or three decades, the horror genre has confined itself to cheesy "boo!"s and worthless bloodfests, only to make audiences today incapable of distinguishing horror from mere surprise or gore. Sudden closeups and jumping out with irritating noises are the only weapons of horror films nowadays, and values like eerieness, ambiguity, bizarreness and inscrutability are forgotten. A few Korean horror films revive these qualities, (usually with the comment that "this is more an arthouse film than a horror flick") and Sorum is at the top of them. The film knows how to strain audiences with space, lighting, composition and silence, let alone its critical allusion to Korean society and people who have lived there. The only problem is, there is no DVD suitable enough to show its horror. May a decent production company abroad like Magnolia discover this masterpiece!

Arahan (2004) -- Actions speak louder than words. This credo of all actionmeisters, and of course, of Ryoo Seung-wan, has never been more exemplified than in Arahan. Usually, the words of action films are the words of fury and anger, as Ryoo often does. In Arahan, however, he punches and kicks to teach, learn, understand each other and live together. (If you don't agree, check out the actions and their meanings in the underrated, 20-minute-long final duel sequence!) Though bloody cries from Die Bad (2000) and The City of Violence (2006) linger on, the self-affirmative energy of Arahan feels more valuable in this post Korean New Wave era.

Arahan (2004) -- Actions speak louder than words. This credo of all actionmeisters, and of course, of Ryoo Seung-wan, has never been more exemplified than in Arahan. Usually, the words of action films are the words of fury and anger, as Ryoo often does. In Arahan, however, he punches and kicks to teach, learn, understand each other and live together. (If you don't agree, check out the actions and their meanings in the underrated, 20-minute-long final duel sequence!) Though bloody cries from Die Bad (2000) and The City of Violence (2006) linger on, the self-affirmative energy of Arahan feels more valuable in this post Korean New Wave era.

The President's Last Bang (2005) -- The President's Last Bang is not a political or historical (in their narrow terms) film about the assassination of Park Jeong-hee. It's about the omnipresent machismo in Korean culture, which has allowed militarism, dictatorship and other kinds of authoritarian activity throughout its history, and especially in the recent era of degradation, the characters and their behavior seem painfully realistic, not remaining as cynical caricatures. This is the undercurrent of Korea I fear the most.

Blossom Again (2005) -- A painfully overlooked gem in the last decade. It's a shame that audiences booed for its not being a typical Kim Jeong-eun romantic comedy. Constructing a maze of signifieds and signifiers, juggling spaces and times, characters, their names, dialogues and actions, this unique love story in the end leaves all earthly materials behind and plays with love itself. That cinematic purity never fails to liberate me.

A Bittersweet Life (2005) -- Most Korean gangster films readily identify with their gangster protagonists. Even if you don't agree with their lifestyle, the perspectives and structures of gangster films usually go along with the protagonists' desire, fury, and despair. In this context, we can say the Korean gangster film genre is still in its "classical" era. A Bittersweet Life is a rare exception. The film is driven by the protagonist's misunderstanding, or even bluffing himself into ignoring the shallow motif under his luxurious surface. It deals with the emptiness of the gangster lifestyle (or the genre itself), rather delves into it. Among Kim Jee-woon's "luxurious wallpaper trilogy," (the other two are A Tale of Two Sisters (2003) and The Good, The Bad, The Weird (2008), though the latter doesn't give much focus to walls) this one goes beyond its exuberant style farthest and best.

The Host (2006) -- With that mutant tadpole... thing alone, The Host deserves its place here. Among director Bong Joon-ho's panorama of Korea, Memories of Murder (2003) or Mother (2009) may be greater in their thematic/structural terms, but who could ever have thought this country would have such a masterpiece in "a genre only for children?"

The Chaser (2008) -- There have been so many would-be thrillers after the success of Old Boy (2003), but rarely a successful one. It seems only The Chaser stands alone in its own place, by catching the atmosphere of contemporary Korea. With his deft use of locations, director Na Hong-jin captures the fear of living in an exploitative, indifferent metropolis, Seoul. In one scene, the film shows a vision of a night: anonymous alleyways intertwined below the burning red crosses of too many churches. The vision asks -- how many brutalities lurk there that we've never known and will continue to ignore? That was the most vivid landscape of Korean city life, and the most scary vision in the last decade.

Thirst (2009) -- Thank God, I don't have to choose among the vengeance trilogy! And this is not a bit a lesser, evasive choice. For me, Thirst is one heartfelt love story about complementary lovers. We've seen too many romantic lovers saying "I can't live without you," I know. But Park Chan-wook delivers it with a penetrating intelligence. Instead of being overwhelmed by emotion only, his characters analyze, dissect, and justify their acts of love, that is, also their acts of hatred and violence. Through their reasoning attempts, love reveals the cowardice and meanness in them, and the more miserable they become, the more complementary they are to each other. This is a rare example of a love story charged with both sense and sensibility, which only a few directors like David Cronenberg or John Cassavettes could achieve.

Thirst (2009) -- Thank God, I don't have to choose among the vengeance trilogy! And this is not a bit a lesser, evasive choice. For me, Thirst is one heartfelt love story about complementary lovers. We've seen too many romantic lovers saying "I can't live without you," I know. But Park Chan-wook delivers it with a penetrating intelligence. Instead of being overwhelmed by emotion only, his characters analyze, dissect, and justify their acts of love, that is, also their acts of hatred and violence. Through their reasoning attempts, love reveals the cowardice and meanness in them, and the more miserable they become, the more complementary they are to each other. This is a rare example of a love story charged with both sense and sensibility, which only a few directors like David Cronenberg or John Cassavettes could achieve.

Paju (2009) -- Perhaps the most personal and contemporary choice in this list. For the past three years, the Korean government has forced so many people to think and act in political terms. Korean history has always been extremely political, but it seems that never before have "ordinary" (politically indifferent) people been so sensitive to their political environment since the military dictatorship finished in early 90s. Suddenly we have been forced to become aware of too many social injustices and the need for protest against our government. At the same time, however, such an overheated atmosphere accompanies the guilty consciousness that my political remarks may be just hypocritical, fashionable ones, or a reactionary repulsion that too many facets of my life are viewed in political terms. Paju interweaves those anxieties at the center of political turbulence. People lose their home under reckless land development, a white collar leftist can't shake off his guilty consciousness, and a teenage girl's sprightliness and sexuality should be suppressed. The film shows we can't always judge who is right and who is wrong fundamentally, in this world where a person's fluttering emotion is linked too tightly with public good and evil. I can't describe these days in Korea better than this.

(Hong Jiro has been one of many veiled volunteers of Koreanfilm.org until this list. His contribution has been confined to programming part because of his insufficient English ability he says, but he knows it's only a typical symptom of Englishphobia which many Koreans share. At this moment, Jiro both sighs for and expects his second step to come as a contributor, that is, as a reviewer.)

Lance Crayon

Save the Green Planet (2003) -- One of the reasons why I love this film is because the director hasn't done anything else. Where is Jang Joon-Hwan? We need more from him now.

Sympathy for Mr. Vengeance (2002) -- Not only does Park Chan-wook prove his skills as a director, he proves he's also a talented writer with his first installation of the "Vengeance Trilogy." It's my favorite of the three.

Chihwaseon (2002) -- It wouldn't be right to make a list of Korean films and not include the master Im Kwon-taek. It's a great historical gem and the cinematography is some of the finest you'll see in Korean cinema.

Memories of Murder (2003) -- It takes real skill to incorporate humor into a serial killer drama, and Bong Joon-ho pulls it off well.

3-Iron (2004) -- Easily my favorite Kim Ki-duk film. This is a pure performance driven piece from a director who understands the power of acting and storytelling without having to rely on dialogue.

3-Iron (2004) -- Easily my favorite Kim Ki-duk film. This is a pure performance driven piece from a director who understands the power of acting and storytelling without having to rely on dialogue.

Old Boy (2003) -- Okay, I'll include it.

Friend (2001) -- You could argue who lit the fuse of the Korean Wave, but my answer has always been the same, Kwak Kyung-taek. I wish more films were made in Busan.

A Bittersweet Life (2005) -- Kim Ji-woon's gangster pic is a well crafted experience, and one of the few Korean films where the characters use guns. However the real surprise here is Hwang Jeong-min. He only has three scenes, but had he been given more he would have stolen the show.

Daytime Drinking (2008) -- I always leave room for DIY filmmakers, and this is one of the best "no-budget" films I've seen in a long time. Young Seok-no is proof that you don't need a lot of money to make a film. All you need is friends, a camera, and a good story.

The Chaser (2008) -- Na Hong-jin's first feature captures the the grime, darkness, and rainy streets of Seoul quite well due in part to his skill as a commercial director, and his excellent DP. Let's hope an embarrassing remake doesn't happen.

Honorable Mention: Rough Cut (2008) -- I know we were only supposed to include ten films, but this unique debut feature from Jang Hoon is too clever to go unnoticed. It's an entertaining education on acting and the Korean film industry, plus the fight scenes rock.

(Lance Crayon lived and worked in Seoul from July 2008 to October 2009. During that time he taught the Wonder Girls and worked on the film catalogue for the 14th Annual Pusan International Film Festival. He is currently in Beijing and will return to Korea sometime this spring. He can be reached at lance.crayon@gmail.com.)

Kyu Hyun Kim

The decade following 2000 has been a period of exponential growth, stunning technical improvement and explosively swift international recognition of Korean cinema (and TV dramas). The term "New Korean Cinema" that, strictly speaking, also includes the motion pictures released in late 1990s, has become an accepted term for scholars, critics and journalists, implicitly indicating the thorough lack of anticipation for this phenomenon on their part. Even during mid-1990s, few Koreans, much less non-Korean students of cinema, expected the Korean cinema to make such an impact on the global scene in such a short period of time. No one knew it was going to happen, that's the truth, my dearies, and boy, am I glad to be here, wading through a glut of positively wonderful films of all conceivable genres and styles, made by those Korean-speakers (Can it really be?!) who I am convinced have migrated to Earth from the same weird, alien planet I used to live.

In recent months, there was nothing quite so much like Darcy's mandate to choose the ten best Korean films of the decade that violently whipped up two distinctive impulses in me. One was the urge to attack, snap, bite and gnaw at the kind of haughty "critic's choices" thrown about on the occasions like this, a list usually composed of the grand auteur's newest sublime masterpieces, philosophically erudite (so they wish!) reflections on the human condition, free-form essays supposedly writ with free, stream-of-consciousness mis-en-scene but in reality rigidly submissive to the "codes" that define what an Art Film should be like, more often than not featuring academics/writers/filmmakers as main characters drinking soju like whales or puffing cigarette smoke like human chimneys, with a few really obscure "indie" titles knowingly (but in truth, condescendingly) thrown in. Just to map out the negative (as in "negative" film) image of the best-of list of this ilk, I briefly contemplated drawing up a list composed of the films like The Butcher, The Rocket Has Launched and Hera Purple and writing a cranium-bursting "academic" essay "rehabilitating" their qualification as serious works of art, filled with choice "relevant" quotations from the likes of Walter Benjamin, Slavoj Zizek, Michel de Certeau, etc. But hey, even a hostile parody requires a substantive engagement with the object of the said parody: I simply could not work up enough energy to be bothered.

The other impulse was to roll up my sleeves and go out to bat for the movies that I truly love. That's right, one more round of defensive bout, insisting that Park Chan-wook still remains possibly the most unfairly underestimated filmmaker in the world today, arguing why a "black-hair-ghost"-infected horror flick like Shadows in the Palace (2007) is nonetheless a decidedly superior film to the international festival favorites like Woman is the Future of Man (2004), pontificating why it is best to watch movies directed by women artists before one makes numbskull generalizations about the alleged misogyny and persecution of women in Korean culture, and so on. In the end, this was not really what I wanted to write about either, and working on it had the undesirable effect of pushing my blood pressure up to dangerous levels.

In the end, I simply banished all "objective," academic, film-scholarship, film-journalist considerations out of my addled brain and decided to go for an unadulterated declaration of the primitive caveman's love: something like a primal scream of a Cro-Magnon man who just happened to have laid his saucer-eyes on the painted figure of woolly mammoth that brings back, or brings forward, all the terror and wonder of encountering a real one in the middle of the frozen tundra: or like an extremely unhealthy attachment of a very unruly child to his favorite, magical toy. When you are willing to arm yourself to the teeth to prevent the DVD copies of certain movies from being snatched out of your hands, then you know these babies truly deserve to be on a list like this.

Even though I quite humbly submit my list for your perusal, and am ready to accept disapproval or even derision with considerable equanimity, I do not consider it merely a reflection of my tastes. I don't know about you folks, but when I am defending a great film this is not a question of taste. Is everything everybody spits out merely a piece of opinion everybody is entitled to? Sounds like contemporary, post-Fox News American political discourse. What a load of (to use Roger Ebert's favorite expression) cow manure. Hence, please do understand that the choices I have put below are derived from my deepest convictions and I am willing to draw blood defending the honor of the movies mentioned herein. All this talk about banishing academic considerations should not fool you into thinking otherwise.

Finally, I also decided to completely forego any concern about disentangling my personal experience from the choices below. Some of the movies listed are there for (perhaps obnoxiously) personal reasons, but that personal dimension is a part and parcel of why I still remain so deeply attached to Korean cinema. Please don't misjudge me: this has very little to do with my surname. Instead, it has a huge chunk of deal to do with the fact that I am the generational equivalent of the major Korean directors who have risen to the worldwide fame in the 2000s, even with the common educational and popular-cultural experiences (In case you are wondering, I am the same age with Park Chan-wook). So it is natural that I favor their works and I am thoroughly unabashed of that fact. But not to worry. Already in my field, younger scholars with superior linguistic and analytic skills are rising up to render obsolete the old fogeys like me, still clinging to the glorified memories of the '80s "movement." The future of Korean cinema is even brighter than academia if anything, no matter how obstinately various socio-economic factors (and the occasional dunderhead policy-makers mud-slinging dunderheaded policies to see if they stick on the wall) try to drag it down into the puddle. I sure heck have more faith in Korean filmmakers than I have in Korean academics, journalists, politicians and "men of literature."

Onward with the list, then: Long live Korean motion pictures!

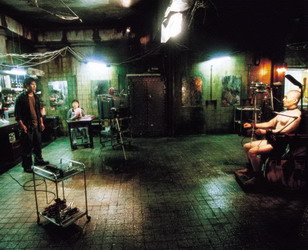

10. Save the Green Planet! (2003)

I wavered a whole week between A Tale of Two Sisters (2003: Two thousand three, what a banner year for Korean cinema!) and this debut film by Jang Joon-hwan, both flawed yet utterly unique films overflowing with creative juices, for this slot. I even thought about cheating and submitting them together as one choice, but I decided against it in the end. Even though as far as I am concerned Kim Jee-un deserves all the kudos he has received, and I certainly hold A Tale of Two Sisters and A Bittersweet Life (2005) in high regard (much higher regard, in fact, than many similar-themed Hong Kong, Japanese and European films that critics usually go ga-ga over), Save the Green Planet! is something special. A genre-busting black comedy/grotesque horror/alien-invasion science fiction film with an almost disturbingly sincere performance by Shin Ha-gyun, one of Korea's best actors, at its center, Save the Green Planet! has a totally unexpected emotional resonance that leaves many first-time viewers reeling by the (literally and figuratively) devastating ending.

I wavered a whole week between A Tale of Two Sisters (2003: Two thousand three, what a banner year for Korean cinema!) and this debut film by Jang Joon-hwan, both flawed yet utterly unique films overflowing with creative juices, for this slot. I even thought about cheating and submitting them together as one choice, but I decided against it in the end. Even though as far as I am concerned Kim Jee-un deserves all the kudos he has received, and I certainly hold A Tale of Two Sisters and A Bittersweet Life (2005) in high regard (much higher regard, in fact, than many similar-themed Hong Kong, Japanese and European films that critics usually go ga-ga over), Save the Green Planet! is something special. A genre-busting black comedy/grotesque horror/alien-invasion science fiction film with an almost disturbingly sincere performance by Shin Ha-gyun, one of Korea's best actors, at its center, Save the Green Planet! has a totally unexpected emotional resonance that leaves many first-time viewers reeling by the (literally and figuratively) devastating ending.

I never in wildest dreams expected my fellow Koreans to make a movie like Save the Green Planet!. Not from the countrymen who used to consider Raiders of the Lost Ark a "children's movie" or overwhelmingly paid for in ticket sales The Spy Who Loved Me over Jaws or Star Wars. The year 2003 was the year that finally made me mutter in stupefied disbelief, "Holy Mackerel, ANYTHING goes in Korean cinema!" Too bad things have been ever so slow to move up since then.

9. Secret Sunshine (2007)

After watching it four or five times, I know now that I prefer Lee Chang-dong's Secret Sunshine over his better-known and better-respected Peppermint Candy (2000) and Oasis (2002). Perhaps the reason is as trivial as that I prefer Song Kang-ho and Jeon Do-yeon's unassuming acting styles over Seol Kyung-gu's extravagant Method approach. However, it might also just be that I ultimately resonated more with the seemingly un-prepossessing "true love is holding up the mirror in front of the loved one" message of Secret Sunshine over the "romantic" resolution of Oasis or the "in the beginning we were all innocents" tragic rumination of Peppermint Candy.

You smart kids know that life has no meaning, there is no God (or he is utterly indifferent, which is the same thing) and human beings are vicious little ugly carnivorous animals wholly undeserving of being the custodian of this luscious planet. So you make Great Works of Art to show us this wisdom, eh? I am sorry but the repertoire is getting awfully stale. Show us something a little different, please, 'cause I already have had my full of those nuggets of wisdom. Secret Sunshine may not be a perfect film but it tries hard to show us something beyond the Wisdom that Life Sucks and There is No God. And it's got Jeon Do-yeon. It is a freaking miracle that we Koreans have an actress like Jeon Do-yeon. As far as I am concerned, that's the proof right there that there is God, or Grandpa Dangun at least.

8. This Charming Girl (2004)

Director Lee Yoon-ki has now made a series of minimalist but rich observations of human characters, starting with this deceptively simple story of a young post office worker, slowly revealing her inner self to the viewers and other characters over the course of resolutely non-melodramatic daily lives (Well, there is one concession to the presence of her childhood sexual trauma, which would have been a critical misstep, were it not for the fact that many real-life young women routinely go through and have to live with experiences like this). Acted with tremendous gumption by Kim Ji-soo, Jeong-hye, the "charming girl" of the title, is the kind of "supporting" figure who would not merit a sidelong glance in the usual, overripe Korean melodramas. In This Charming Girl, she takes the center stage.

Fully in control of the elements, Lee nonetheless shows great respect toward his character's private space and her internal state of being. So many "artistic" directors, in the name of creating art, violates, destroys, tramples and tears apart the psychological and spiritual integrity of their characters, usually young women. They peel their skin inside out like oranges to "expose" what a bunch of damaged goods "we" are. The day when you seriously believe the blighted humanoids populating The White Ribbon or Anti-Christ are somehow telling us anything more "profound" than what Lee Yoon-ki is saying through Jeong-hye, is when you, sir, should maybe quit watching Cinematic Art, eat some junk food, and adopt a new kitten.

Fully in control of the elements, Lee nonetheless shows great respect toward his character's private space and her internal state of being. So many "artistic" directors, in the name of creating art, violates, destroys, tramples and tears apart the psychological and spiritual integrity of their characters, usually young women. They peel their skin inside out like oranges to "expose" what a bunch of damaged goods "we" are. The day when you seriously believe the blighted humanoids populating The White Ribbon or Anti-Christ are somehow telling us anything more "profound" than what Lee Yoon-ki is saying through Jeong-hye, is when you, sir, should maybe quit watching Cinematic Art, eat some junk food, and adopt a new kitten.

7. The Past is a Strange Country (2008)

I am choosing Kim Eung-su's Past is a Strange Country over such better-known documentaries such as Kim Dong-won's Repatriation (2004) or Park Jin-pyo's semi-fictional Too Young To Die (2002) for this slot. I have worked very hard to provide what I think is my best English subs ever for this film, but even without my contribution, it still is the most challenging documentary about Korean history and politics I have ever seen.

The Past will never be popular: neither is it the easiest film for non-Koreans to understand, despite its frankly universal subject matter-- memories of the '80s student movements that allegedly laid foundation for Korea's democracy today. Neither the right nor the left eggheads in Korea are likely to appreciate it for what it is: an anti-agitprop, anti-propagandistic, severe, austere and almost mystical meditation on the mind-bogglingly traumatic event of witnessing the self-immolation suicide of a fellow student activist. Almost entirely consisting of the now forty-something former student activists speaking toward the camera, in a wide range of states of serene acceptance, calm rumination and unexpected bursts of emotion, The Past is a powerfully honest exploration of the turbulent '80s and just about the only post-'90s Korean movie about the politics of my generation that I can flat-out admire.

6. Take Care of My Cat (2001)

This cool cat, once an object of the popular campaign to "save" it at the box office, along with the equally independent-minded Nabi (2001), Waikiki Brothers (2001) and Ray-Bang (2001), is seemingly a nondescript tale of three young women growing up in late '90s Korea, full of quirky dreams, and artistic or other aspirations, yet running into expected frustrations and disappointments of adult life. But I keep thinking that there is a different kind of beast lurking under its smooth, lovely fur: something with much sharper claws and the almost cold, jewel-like eyes that burn through the standard bullshit of the male-dominated Korean society.

Seen from today's point of view, Take Care of My Cat is remarkable not only for its honest, non-sentimental look at the "ordinary" young Korean women, a demographic consistently ignored and/or exploited in Korean popular culture until the advent of "New Korean Cinema," but also for director Jeong Jae-eun's modernist sensibility that gives a startling air of futuristic science fiction to the Seoul and Inchon cityscapes. Along with the surrealistic "His Story" segment of the human-rights omnibus If You Were Me (2003), Jeong's films are like beautiful pictures illustrated by the beams of tachyon projected from Korea's future, where, presumably, someone like Bae Doo-na is in firm control and the brains of the macho middle-aged soccer-loving Korean men are recycled for cat food.

5. Mother (2009)

Some of you may have been surprised that I did not select Memories of Murder (2003) or The Host (2006) for this slot. Well, I liked Mother more. It is not only that Mother carries more juices as an artistic achievement (which can be debated), but also that this film proves beyond doubt that director Bong Joon-ho is the most trenchant critic of the ills of Korean society. Mother is a veritable compendium of the hypocrisies and "little sins" of a typical medium-sized rural city in Korea. It's as if the things that Bong could not say in his previous films, chafed by the demands of a genre thriller or a monster movie, he decided to pour all out in one-shot deal this time. Without ever employing the scolding, holier-than-thou tone of a typical left-wing Korean egghead, or sensationalizing the sordidness and squalor of the underclass for the sake of "enlightenment" of the audience (as if South Korea is the only country in the world with economically disadvantaged people), Bong calmly lays out how the maws of moral hypocrisy, indifference and casual violence masticate the weak and the defenseless into the bloody pulp that in turn feeds everyday "normal" reality of the Wonder-Girls-loving, Yuna-Kim-loving "ordinary" Koreans. No monkey-ing about the allegedly mad cow disease-infected McDonald hamburgers in this film: the misery suffered by Korean characters in this movie is squarely the product of their own. Even mother's blind love for her son is tinged with the homicidal intent and deed.

Some of you may have been surprised that I did not select Memories of Murder (2003) or The Host (2006) for this slot. Well, I liked Mother more. It is not only that Mother carries more juices as an artistic achievement (which can be debated), but also that this film proves beyond doubt that director Bong Joon-ho is the most trenchant critic of the ills of Korean society. Mother is a veritable compendium of the hypocrisies and "little sins" of a typical medium-sized rural city in Korea. It's as if the things that Bong could not say in his previous films, chafed by the demands of a genre thriller or a monster movie, he decided to pour all out in one-shot deal this time. Without ever employing the scolding, holier-than-thou tone of a typical left-wing Korean egghead, or sensationalizing the sordidness and squalor of the underclass for the sake of "enlightenment" of the audience (as if South Korea is the only country in the world with economically disadvantaged people), Bong calmly lays out how the maws of moral hypocrisy, indifference and casual violence masticate the weak and the defenseless into the bloody pulp that in turn feeds everyday "normal" reality of the Wonder-Girls-loving, Yuna-Kim-loving "ordinary" Koreans. No monkey-ing about the allegedly mad cow disease-infected McDonald hamburgers in this film: the misery suffered by Korean characters in this movie is squarely the product of their own. Even mother's blind love for her son is tinged with the homicidal intent and deed.

4. Die Bad (2000)

Watching Ryu Seung-wan's debut film for the first time was a visceral experience like being punched in the stomach. Bristling with raw intelligence, desperation and anger, yet suffused with almost eerily sophisticated humor, this mini-crime epic is also one of the finest examples of guerrilla filmmaking that taekwondo-kicks into smithereens the conventional distinction between commercial and "independent" cinema. It is unfair to confine Ryu into the category of a filmmaker who "someday will fulfill the promise shown in Die Bad." However, that consideration will not deter me from naming Die Bad one of the best Korean films of 2000's or any other decade. Promise or whatever, you should all be so lucky to just make one movie that is as powerful, gut-wrenching and searingly real as Die Bad before you die.

3. One Fine Spring Day (2001)

Still the most beautiful Korean film I have ever seen, which is really saying something considering the height of visual splendor scaled by the best of the New Korean Cinema, One Fine Spring Day's thwarted-romance story now appears to be the least important aspect of the film. The movie is a contradiction in terms. It's like Basho's haiku, collected yet heartfelt, its essence somehow expressed through the multitude of brilliant colors, luscious greens, warm golds and deep-set crimsons. It's like an impressionist painting that renders all the details of its emotional landscape photographically, absurdly clear. Director Hur Jin-ho now seems to be typecast as a specialist of "quiet melodrama" chiefly on the strength of Christmas in August (1998) and this film, but to call this movie a Korean-style melodrama is like calling Leonardo Da Vinci an "inventor."

2. Sympathy for Mr. Vengeance (2002)

What can I say about this film that I have not already said? I know, I gotta write a book about it. I will, yet.

Sympathy will someday be considered one of the greatest cinematic achievements, perhaps the greatest cinematic achievement, of early 21st century. I am serene in my faith that this will come true, as only someone with true convictions, not the crazy convictions of a fanatic, can be. Fanatics need to blow up things, harm others, or at least scream and holler on a daily basis to prove their points: I don't have to.

Oh and just to get you riled up one more time: Park Chan-wook is a genius. Park Chan-wook is a great filmmaker. Park Chan-wook is still underappreciated by the likes of you!

1. Old Boy (2003)

Here it is, My Favorite Korean Film of the Last Decade. Come on, don't act surprised, you surely have heard about this little crazy son-of-a-gun of a movie, otherwise can you really call yourself a serious connoisseur of contemporary cinema? Smirk.

Here it is, My Favorite Korean Film of the Last Decade. Come on, don't act surprised, you surely have heard about this little crazy son-of-a-gun of a movie, otherwise can you really call yourself a serious connoisseur of contemporary cinema? Smirk.

This choice is not a concession to the popularity game, I must tell you. I deeply, obstreperously, heinously love this movie. Of course, Old Boy is full of flaws, and does falter (albeit in interesting ways) both as a straightforward crime thriller or a quasi-surrealistic meditation on the biblical themes of sin and redemption. We can question Director Park Chan-wook's choices in numerous spots. What is with all this stuff about hypnotism? Can we really rely on Korean gangsters to run a high-tech private prison for fifteen years? Seriously, how could we possibly believe that Choi Min-sik and Yoo Ji-tae belong to the same generation, if not exactly the same age? And of course, does Oh Dae-soo have to swallow the live octopus head-first? I mean, really? You, I and Director Park know that Koreans don't pull off crazy stuff like this in real life, even if someone pays them a lot of money.

But Old Boy nonetheless belongs to this position in my list. Why? Because when I enter a movie theater, turn off my cell phones, make sure my jackets are safely spread out on my knees, and train my over-used, sometimes blood-shot eyes on the screen, it is precisely the film like Old Boy that I crave to watch.

Motion pictures like Old Boy is the reason why I watch movies, why I collect more than one hundred-fifty-plus DVDs and Blu Rays every year, why I continue to have faith in the creativity of motion picture as an artistic medium. Old Boy, flawed as it is (and what, you gonna tell me Luis Bunuels, Jean Renoirs and Jean-Luc Godards of the world only made perfect movies?), squarely points us toward the future of cinema. You don't like it, man, drop out. I am happy to go along with the journey, here and there be tigers and elephants.