1945-1959

From left: "Piagol" (1955), "Madame Freedom" (1956), "The Female Boss" (1959), "A Flower in Hell" (1958)

On August 15, 1945, Korea was finally liberated from its long colonization by Japan. Whereas just a few years earlier, Korean filmmakers were shooting propaganda films in Japanese, now for the first time they had the freedom to celebrate their own culture on film. However, with equipment in decrepit condition and film stock in short supply, a comparatively small number of films and newsreels were made in the second half of the decade, mostly on 16mm. Most famous was Choi In-gyu's Hurrah, Freedom! (1946), a film about resistance fighters in the last days of the Japanese occupation.

Around this time Korea was divided into North and South by the occupying armies of the US and USSR, causing great anxiety and consternation among the populace. Within the film industry as well, groups representing various ideologies formed and competed for influence. Controversially, the US governing authority in the South decided to leave in place the censorship apparatus set up by the Japanese, which caused various hurdles especially for left-leaning filmmakers.

The outbreak of civil war in 1950 caused tremendous damage to the nation as a whole, and during this time the film industry almost -- but not quite -- disappeared. Filmmaking moved to southern cities like Busan and Daegu, where future master Shin Sang-ok made his debut in 1952 with the 16mm Evil Night (a film which no longer exists).

The aftermath of war saw the country desperately poor and in need of reconstruction. Surprisingly, however, the film industry made a quick recovery -- touched off by the commercial successes Chunhyang-jeon (1955) and Madame Freedom (1956). Thanks to tax cuts and the enthusiastic support of the populace, production boomed and the country went from making 18 films in 1954 to 111 films in 1959. The late fifties make up the early section of the Golden Age of Korean Cinema, and are characterized by films which rushed to embrace Western fashion, lifestyle, and all things modern. For the first time ever, Korea had a more or less normally functioning film industry.

Reviewed below: Hurrah! For Freedom (1946) -- Hometown of the Heart (1949) -- The Hand of Fate (1954) -- Piagol (1955) -- The Widow (1955) -- Yangsan Province (1955) -- Hyperbola of Youth (1956) -- Madame Freedom (1956) -- The Wedding Day (1956) -- Money (1958) -- A Flower in Hell (1958) -- A College Woman's Confession (1958) -- A Sister's Garden (1959) -- The Female Boss (1959).

| 1950 | 1951 | 1952 | 1953 | 1954 | 1955 | 1956 | 1957 | 1958 | 1959 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 5 | 5 | 6 | 6 | 18 | 15 | 30 | 37 | 74 | 111 |

Source: Traces of Korean Cinema from 1945 to 1959 (2003), Korean Film Archive.

Short Reviews

These are some reviews of the features released from this era that have generated discussion and interest among film critics and/or the general public. They are listed in the order of their release.

For the directors, actors, and others associated with the Korean film industry who wanted to continue to create under Japanese colonization, (especially what would be the later years of the colonization), their choices were limited to primarily pro-Japanese fare. Initially, this frustrated Choi In-kyu enough that he vowed to stop making pro-Japanese films after Homeless Angel in 1941. However, director Han Hyeong-mo convinced Choi to return to the director's chair, and Choi did eventually complete the pro-Japanese trilogy, Children of the Sun (1944), Vow of Love (1945), and Sons of the Sky (1945). Children are encouraged by a schoolteacher to willingly join step with the Japanese military march in the first film, and to show their love for the colonizer by becoming Japanese citizens in the second. The third, as if the first one wasn't enough, encourages Korean youth they missed the first time to join the air force. Stuck in this artistic bind that the Japanese colonialism imposed, when the occupation ended, Choi threw himself into a Korean nationalist text with wild abandon - Hurrah! For Freedom.

Ironically, Choi would experience artistic censorship yet again with this film, this time decades later under Park Chung-hee's government. When I was watching this film on DVD, I found the character of Nam-bu, a Korean collaborator with the Japanese government played by Dok Eun-gi, confusing. He seemed to be an important character for the narrative, someone to be seen as a rival for the affections of Nam-bu's girlfriend, Mee-hyang (Yoo Kye-sun - Confessions of a College Girl, Chunyang Story), who betrays Nam-bu by helping our Korean nationalist hero Choi Han-joong (Jeon Chang-geun, who would later direct his own films, such as Nakdong River and China Town) hide from the Japanese soldiers. But Nam-bu barely makes an appearance. The reason for this strange absence is not because it was intended by Choi, but because it was demanded by the 70's censors since the actor Dok Eun-gi had, later in life, defected to North Korea. His mere image was unacceptable to government censors when a new print was made in 1975 for a re-release. Because of this, and some other scenes lost through the deterioration of time, we are left with an incomplete look at this important South Korean film.

Ironically, Choi would experience artistic censorship yet again with this film, this time decades later under Park Chung-hee's government. When I was watching this film on DVD, I found the character of Nam-bu, a Korean collaborator with the Japanese government played by Dok Eun-gi, confusing. He seemed to be an important character for the narrative, someone to be seen as a rival for the affections of Nam-bu's girlfriend, Mee-hyang (Yoo Kye-sun - Confessions of a College Girl, Chunyang Story), who betrays Nam-bu by helping our Korean nationalist hero Choi Han-joong (Jeon Chang-geun, who would later direct his own films, such as Nakdong River and China Town) hide from the Japanese soldiers. But Nam-bu barely makes an appearance. The reason for this strange absence is not because it was intended by Choi, but because it was demanded by the 70's censors since the actor Dok Eun-gi had, later in life, defected to North Korea. His mere image was unacceptable to government censors when a new print was made in 1975 for a re-release. Because of this, and some other scenes lost through the deterioration of time, we are left with an incomplete look at this important South Korean film.

But here's the basic story. We begin with Han-joong escaping from prison, after which he finds lodging in the home of the mother of a nurse named Hye-ja (stage name - Hwang Ryuh-hee; real name - Hwang Youn-hee - The Innocent Criminal and The Bloody Road). Working together with other members of the resistance movement, Han-joong and his compatriots plan an armed uprising. However, they run into a snag in their plans when a compatriot acquiring dynamite is picked up by the Japanese. Han-joong runs to his rescue, having to find shelter himself in the home of Mee-hyang. Just like Hye-ja, Mee-hyang begins to fall for Han-joong and finds herself betraying her collaborationist (invisible) boyfriend to assist Han-joong and the resistance.

I'll stop there for those who don't want the entire film relayed to them. But, again, the entire film is not available to us, due to lost and politically pulled scenes. Still, we can see much of Choi's vision and style. The action scenes are decent considering the time in which they were made. There are some nice cut-aways, such as when Hye-ja hopes Han-joong notices the flowers she gave him. And one especially powerful moment of symbolism is the scene in which two characters are shot. Note how their curved bodies fall head to toe on the floor to resemble the red and blue yin-yang that centers the South Korean national flag, Tae-geuk-gi.

We can lament what Choi could have accomplished were he permitted full freedom to invest his artistic efforts throughout his entire career, just as we could lament what he could have accomplished with greater resources. And we can lament what we're missing thanks to the dictator-ly demands of the Korean censors of the 1970's. Such mourning, if productive - that is, true mourning rather than simple pity - can help us in our efforts to prevent such censorship from reoccurring in the future in our own respective nations. But limitations can also offer challenge to create in ways we had never thought of before. And release from previous restrictions can allow for an explosion of artistry. I will lament what could have been and I will revel in what we have. Because what we do have is a window - although one with a broken pane or two - into the national negotiations of the time that Korean artists strived to bring to the screen. Hurrah! For Freedom, indeed. And Hurrah! for archival efforts such as this one by the Korean Film Archive. (Adam Hartzell)

Hurrah! For Freedom ("Jayu-manse"). Directed by Choi In-kyu. Screenplay by Jeon Chang-geun. Starring Jeon Chang-geun, Yu Gye-seon, Kim Seung-cho, Bok Hye-sook, Ha Yeon-nam, Yun Bong-chun, Kang Gye-sik, Dok Eun-gi, Hwang Ryuh-hee. Cinematography by Han Hyeong-mo. Produced by Koryo Film Company. 60 min, b&w. Released on October 21, 1946.

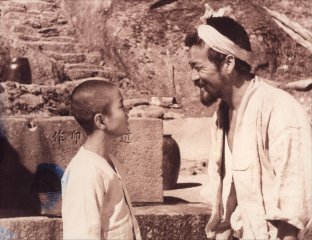

In the Korean Film Archive's publication, Traces of Korean Cinema from 1945-1959, the authors Yi Hyo-in and Chung Chong Hwa note that "In 1949, the Korean film industry produced about twenty films. This level of productivity represented a green light for growth." Out of such growth, director Yoon Yong-gyu completed his Buddhist-themed tale Hometown of the Heart. And when time came to decide what South Korean film would be swapped with France in a cultural exchange, it was Hometown of the Heart that found itself headed to French shores in return for Chanson du Reves. (I have tried to find the director and year of this French film, but have had no success in unearthing such information from the internet, print publications, or my own personal French connections.) Lucky thing for Yong's film since cinephilic France was sure to keep good care of the print, saving it from the almost complete destruction of early Korean cinema as a result of the horrors of war and the carelessness of initial film storage techniques in Korea. Before the recent unearthing of older Korean films such as An Cheol-young's Eowha (1939), Hometown of the Heart was one of only a few films made prior to the outbreak of the Korean War to have survived.

The film takes place around a mountain temple where a boy abandoned by his mother, Do-song, longs for his mother to reappear. The older monks and villagers tell Do-song stories about his mother, keeping Do-song attached to his hopes for her return from Seoul. He is told that if he simply builds her in his heart, she will come. However, the arrival of the Ahn family brings the possibility of yet another mother figure for Do-song. The Ahn family, the main philanthropists who support the temple, have returned to the temple for a funeral for their only male progeny, Jong-bo. Much to the initial disagreement of Grandma Ahn, Jong-bo's Mother takes a liking to Do-song and begins to contemplate adopting him. Do-song takes a liking to Jong-bo's Mother as well. But not simply because of his desire for a mother, but because of his desire for Seoul. When Do-song comments to the Kitchen Master how pretty Jong-bo's Mother is, the Kitchen Master replies, "That's because she's from Seoul." Do-song desires to follow Jong-bo's Mother to Seoul where he imagines the availability of many material things, such as the beautiful feather fan that Jong-bo's Mother possesses. And it is this beautiful feather fan, and Do-song's continued attachment to his biological mother, that risks finally ruining all that Do-song has hoped for.

The film takes place around a mountain temple where a boy abandoned by his mother, Do-song, longs for his mother to reappear. The older monks and villagers tell Do-song stories about his mother, keeping Do-song attached to his hopes for her return from Seoul. He is told that if he simply builds her in his heart, she will come. However, the arrival of the Ahn family brings the possibility of yet another mother figure for Do-song. The Ahn family, the main philanthropists who support the temple, have returned to the temple for a funeral for their only male progeny, Jong-bo. Much to the initial disagreement of Grandma Ahn, Jong-bo's Mother takes a liking to Do-song and begins to contemplate adopting him. Do-song takes a liking to Jong-bo's Mother as well. But not simply because of his desire for a mother, but because of his desire for Seoul. When Do-song comments to the Kitchen Master how pretty Jong-bo's Mother is, the Kitchen Master replies, "That's because she's from Seoul." Do-song desires to follow Jong-bo's Mother to Seoul where he imagines the availability of many material things, such as the beautiful feather fan that Jong-bo's Mother possesses. And it is this beautiful feather fan, and Do-song's continued attachment to his biological mother, that risks finally ruining all that Do-song has hoped for.

Even though the precious nature of this film was enhanced by its previous standing as a rare representation of early Korean Cinema, this film will still be considered a treasure regardless of what other older films are rediscovered in the future. It is considerably well acted and directed with very little of the manic melodrama assumed to infect so much Korean cinema. There is one moment when Do-song's crying seems forced, but this is no different from the acting of children in other nations' cinemas of the time and otherwise the direction of Do-song's reactions and movements flows nicely. Three scenes stand out in the film: a dream sequence that we are drawn in and out of with the nice effect of a tight shot of branches rustling on a tree; a tense moment of secret identity between Do-song, Jong-bo's Mother, and a newly arrived stranger; and the nice subtle humor of the conflicts of interest afforded when the Priest must interpret particular karmic events for his primary benefactor. Sadly, the scene where Do-song first meets Grandma Ahn appears effected by the erosion of time because we cannot see Do-song's important facial reaction in response to the possibilities the Ahn family poses for his future. But who are we to complain when, outside of this and some brief soundtrack problems, the film has been restored quite well.

It is interesting that of all the films to have survived initially, one is a Buddhist-themed film since it is films such as Mandala, Why Has Bodhi-Dharma Left for the East?, and Spring, Summer, Fall, Winter, . . . and Spring that have acted as inroads for Western interest in South Korean cinema. The film also explores intense relationships between sons and their mothers. This is where some might feel I should note the specifically Korean variation of such relationships, that is, between eldest sons and their mothers. Although Korean friends and acquaintances have expressed to me how such relationships are often extremely close to the point of being symbiotic, I have never been a first-party observer of such familial relationships nor have I found proper ethnographic studies of them, thus, I still retain some skepticism regarding their 'uniqueness' to South Koreans. Until I have such observations to reference, I will look at Hometown of the Heart as an exposition of any son/mother relationship that is tightly bonded. Hometown of the Heart allows the viewers to look at such relationships through the lens of a major tenet of Buddhist thought, that all suffering is caused by our attachment to things. In most Western Buddhist commentaries with which I am familiar, the primary attachments addressed are those placed upon material possessions, money, and fame. But equally sufferable are those attachments to fantasies about relationships and the borderline idolatry of other people that can sometimes result. And what better relationship to underscore the suffering of attachment to another person than the often sanctified relationship some men have with their mothers. And how ironic is it that cinephiles, those who are so attached to cinematic treasures from the past, have a Buddhist-themed film as one of the handful of films to survive the Korean War? (Adam Hartzell)

Hometown of the Heart ("Maeum-ui gohyang"). Directed by Yoon Yong-gyu. Screenplay by Kwak Il-byeong. Starring Byun Ki-jong, Yeo Heon-yong, Nam Seung-min, Yu Min, Choi Eun-hee, Seok Geum-seong, Choi Woon-bong, Cha Jin-su. Cinematography by Han Hyeong-mo. Produced by Dongseo Film Company. 78 min, b&w. Released on February 9, 1949.

My first kiss was a cliche. It was in sixth grade with my friend Sarah during a game of Spin the Bottle. By luck of the class assignment draws, Sarah and I had been in the same class from kindergarten through sixth grade. Neither she nor I were attracted to the other, but, well, I don't remember if it was she or I who spun the bottle, but the rules were the rules, and we had to kiss. Sociologists would love to have witnessed this kiss because the way I kissed Sarah was fully influenced by the media I was exposed to as a 12-year old. All the images I recalled showed people open-mouth kissing, so that's exactly how I kissed Sarah. And she responded with a completely justified slap across my face.

And based on what Kim So-young said in her documentary Women's History Trilogy, the first onscreen kiss in a South Korean film, Han Hyeong-mo's The Hand of Fate, was a similar slap to the face of those who weren't able to get a ticket for the box-office-record-breaking Chunhyang Story (dir. Lee Kyu-hwan). The recipient housewives whose eyes were beholden to the screen were reported to emit gasps during the infamous scene. The Hand of Fate was exactly as its title suggested, handing down what was destined to eventually make its way to South Korean screens. Han was going to poke his finger through the fourth wall and show what everyone already knew happens behind the screen consummating relationships. The placement of South Korea's first onscreen kiss on the lips of a North Korean had me thinking about the first interracial kiss on television in the United States. That kiss was between Captain Kirk and Lieutenant Uhuru on Star Trek. The Star Trek kiss was enabled despite a significant part of the White population that still held onto to its anti-miscegenation ways because it took place far away in space and well into the future, so the spatial and temporal distance provided existential distance from this act for viewers whose racism still required such distance. To allow the kiss in The Hand of Fate, Han has a South Korean kiss a South Korean version of the Other - a North Korean spy. Further distance is created from the audience by making her character claim to be "impure" and "vulgar" and by having the kiss take place just before she . . . well, I don't want to give everything away, but you'll probably guess what happens knowing how such a "scandalous" woman needs to be "punished" for daring to be human.

And based on what Kim So-young said in her documentary Women's History Trilogy, the first onscreen kiss in a South Korean film, Han Hyeong-mo's The Hand of Fate, was a similar slap to the face of those who weren't able to get a ticket for the box-office-record-breaking Chunhyang Story (dir. Lee Kyu-hwan). The recipient housewives whose eyes were beholden to the screen were reported to emit gasps during the infamous scene. The Hand of Fate was exactly as its title suggested, handing down what was destined to eventually make its way to South Korean screens. Han was going to poke his finger through the fourth wall and show what everyone already knew happens behind the screen consummating relationships. The placement of South Korea's first onscreen kiss on the lips of a North Korean had me thinking about the first interracial kiss on television in the United States. That kiss was between Captain Kirk and Lieutenant Uhuru on Star Trek. The Star Trek kiss was enabled despite a significant part of the White population that still held onto to its anti-miscegenation ways because it took place far away in space and well into the future, so the spatial and temporal distance provided existential distance from this act for viewers whose racism still required such distance. To allow the kiss in The Hand of Fate, Han has a South Korean kiss a South Korean version of the Other - a North Korean spy. Further distance is created from the audience by making her character claim to be "impure" and "vulgar" and by having the kiss take place just before she . . . well, I don't want to give everything away, but you'll probably guess what happens knowing how such a "scandalous" woman needs to be "punished" for daring to be human.

This woman is Margaret, or Jung-ae (Yun In-ja - A Woman's Life, Red Muffler), a North Korean spy who works in a hostess bar while passing secret messages to the North Korean military through the transposing of classical music scores. The opening sequence is a wonderful montage of swatches of body parts and apartment decor and images representing power and secrecy. This is followed by habits of Margaret's that present her as immoral and deviant, which in Korean means she smokes. While smoking casually, she hears a disturbance and turns to find out it's a rat. But she does not fear the rat. In fact, she smiles at it, with a similar nonchalance as the housemaid in Kim Ki-young's classic. Like that housemaid, Margaret the spy is a "rat in the kitchen" of South Korea. Margaret quickly takes in a poor student named Young-chul (Lee Hyang - The Gate to Hell) after he's been beaten up and they develop a fast relationship after quite forward advances on Margaret's part. This relationship causes Margaret's mysterious superior to be concerned and Margaret and Young-chul's relationship is stalled for a moment. It is at this moment that the film shifts from primarily melodrama to primarily spy thriller. To give you more would ruin the pleasures of discovering the thrills, but I'm sure you're realizing that Young-chul and Margaret will end up in each others arms again. Don't worry, though. There is more to it than that.

Han Hyeong-mo was a cinematographer on many projects, such as the classic Hurrah! For Freedom, before becoming a director. Han is most famous for his film Madame Freedom. And what both films share is an effort to engage with the shifting roles of modern South Korean women. Although Han's "ideologically conservative" views (according to Jo Jun-hyung in the liner notes) required certain repressive resolutions when presenting such women, Han's characterizations also displayed fissures in the disparaging critiques of such women at this time by allowing female characters to have, at moments, a confidence that presented the possibilities of greater freedoms.

Han's visual style is quite evident here, showing the benefits of starting out as a cinematographer. Particularly powerful is the transition from Margaret's code translation into the next scene where superimposed images of bombs demonstrate the results of her espionage. Still, there are moments that are overdone or lacking, such as the over-extended emotive reactions and the poor sound effects accompanying a later fight scene.

I am normally a critic who is cautious to note metaphors about the national division of South Korea and North Korea because I have come across examples where such interpretations appear forced upon the film rather than truly demonstrative within. But The Hand of Fate is practically begging to be interpreted as a metaphor of the divided state of the two Koreas. When the subtitles have Margaret say to Young-chul, "You're so close now, but why have we been so far apart?" it is obvious how Han and screenwriter Kim Sung-min want us to see this in light of the recently divided country. And when Young-chul responds with guidance to "Be strong", we know this line is intended for the audience as well. And seeing this film now, one can't help but have visions of Shiri dancing in one's head. As film critic Byun Jae-ran notes, The Hand of Fate "created a new type of female figure in the movies" of South Korea, and Han was determined to continue on defining these female figures just as the women watching continued on defining themselves, gasping for breath, and waiting to exhale. (Adam Hartzell)

The Hand of Fate ("Unmyeong-ui son"). Directed by Han Hyeong-mo. Screenplay by Kim Seong-min. Starring Yoon In-ja, Lee Hyang, Joo Seon-tae. Cinematography by Lee Seong-hwi. Produced by Han Hyeong-mo Productions. 85 min, b&w. Released on December 14, 1954.

It's 1953, just after the armistice that concluded the Korean Civil War in an armed truce that continues to this day. A dwindling group of Communist partisans roams the countryside around Mt. Jiri south of the 38th parallel. Their supply lines have been cut, and Southern forces are hunting them down. Between scavenging and raiding they hide out in a gorge called Piagol, their morale sinking by the day.

Piagol was attacked on political grounds on its release, for being insufficiently anti-Communist. Those criticisms were accurate enough as far as they went: Piagol isn't really an anti-Communist film, nor is it about the Korean War. It's a moral tale

that reminds me of "The Pardoner's Tale" from Chaucer's Canterbury Tales, in which three young men kill each other for possession of a hidden treasure. In Piagol the guerillas are killed off progressively by Southern forces, by their cruel Captain Agari (Lee Ye-chun), or as they fight over the two women in their cohort. One of the women isn't just a passive token, though. Comrade Ae-rin (Noh Kyung-hee, Madame Freedom) looks as tough as Brando in her

khaki trousers and leather jacket. Outwardly she's a cold-blooded Party ideologue, but privately she looks out only for herself. She wants Comrade Chul-soo (Kim Jin-kyu), perhaps because he seems to be indifferent to her. Comrade Oh So-ju is almost Captain Agari's concubine; when she's transferred to the central Party office, things turn out even worse for her there. Agari gets a commendation from Commander Cho Byung-ha; the other soldiers get a pig, and Cho takes So-ju with him.

that reminds me of "The Pardoner's Tale" from Chaucer's Canterbury Tales, in which three young men kill each other for possession of a hidden treasure. In Piagol the guerillas are killed off progressively by Southern forces, by their cruel Captain Agari (Lee Ye-chun), or as they fight over the two women in their cohort. One of the women isn't just a passive token, though. Comrade Ae-rin (Noh Kyung-hee, Madame Freedom) looks as tough as Brando in her

khaki trousers and leather jacket. Outwardly she's a cold-blooded Party ideologue, but privately she looks out only for herself. She wants Comrade Chul-soo (Kim Jin-kyu), perhaps because he seems to be indifferent to her. Comrade Oh So-ju is almost Captain Agari's concubine; when she's transferred to the central Party office, things turn out even worse for her there. Agari gets a commendation from Commander Cho Byung-ha; the other soldiers get a pig, and Cho takes So-ju with him.

The complexity of their motives probably explains South Korean censors' objections to the film: the characters are too human, not one-dimensional Red caricatures. (The censors didn't object, however, to the bared breast and nipple of a dead woman in Namanli village during the night raid.) In the end, only one guerilla survives, and because of the censors' demands, that survivor walks away into a superimposed South Korean flag which fills the screen.

Piagol was made only two years after the war ended, when South Korea was still desperately poor, with limited resources. It looks even older than it is; the outdoor long shots look like old silent films, though interiors and closeups are often clear, rich in tone, and beautifully composed. Camera movement is mostly limited to pans, though there is one tracking shot that is very effective, mainly because it's the only one in the film. (A year later, in 1956, Han Hyeong-mo would build a crane for Madame Freedom.)

Piagol is still very striking visually. It was filmed in autumn, using the natural backgrounds of ice, rock, bare trees, fallen leaves, fields, and streams, but by action-movie standards it's not very exciting. The pace is leisurely, with long takes that mainly seem to pad out the running time. Most of the killings occur off-screen, which no doubt saved money on makeup effects, but adds to Piagol's stylized, old-fashioned look. The sound is clear enough, but you can hear the acoustics of the room where the dubbing was done. It's distracting, especially when the characters are outdoors but sound like they're yelling at each other in an empty warehouse.

Director Lee Kang-cheon made the cast live like partisans, sleeping in their costumes, and this gives them an authentic look, though I did wonder where Comrade Ae-rin got her cosmetics. But the men, anyhow, look scruffy and unwashed, and show the exhaustion of soldiers who know their time is running out. After two viewings I'm still not sure whether I like Piagol, but Lee had an artist's eye that Kim Ki-duk must envy. His refusal to dehumanize the enemy looks forward to films like Joint Security Area, and is even more daring given the era in which he worked. (Duncan Mitchel)

Piagol ("Piagol"). Directed by Lee Kang-cheon. Screenplay by Kim Jong-hwan. Starring Noh Kyung-hee, Lee Ye-chun, Kim Jin-gyu, Heo Jang-gang, Yun Wang-guk, Song Kwak-sang, Lee Won-cheol. Cinematography by Kang Young-hwa. Produced by Baekho Production. 106 min, b&w. Released on September 23, 1955.

One of the unique aspects of New Korean Cinema as a national cinema movement was the presence at the start of not one, but three significant female directors - Lim Soon-rye, Byun Young-joo, and Jeong Jae-eun. Lim's second film, Waikiki Brothers (2001), was a considered portrayal of deferred dreams. Byun Young-joo's 'Comfort Women' Trilogy of documentaries (1995, 1997, & 1999) were stories that needed to be told for far too long, and needed to be told by the survivors who lived through the horrors of WWII sexual servitude. They still stand arguably as the most important documentaries made by a South Korean director. And Jeong's Take Care of My Cat (20001) is a canonical film of New Korean Cinema. A wonderful story of the evolving friendships of young women with a narrative that refuses to tie their lives to the needs of men. If a list of essential films of New Korean Cinema doesn't include Take Care of My Cat, it will be hard for me to take the list seriously. There is a reason a still from that film is on the cover of Shin and Stinger's book New Korean Cinema (Edinburgh University Press, 2005). It is an important film about female friendship and the intersection of class and gender in South Korea with an excellent ensemble. Plus, it still has the best soundtrack of any South Korean film.

Having followed the emergence of New Korean Cinema from the beginning, when popular movie news website Indiewire posted a primer on "10 Essential Films of the Korean New Wave" (June 26, 2014) that not only didn't mention Take Care of My Cat, but dismissed female directors all together, I knew we had a problem more serious than the fact that the authors were really talking about New Korean Cinema, not the Korean New Wave. I realized that those who have come later to New Korean Cinema than those of us here at Koreanfilm.org might have gaps in their knowledge of the movement. They might take the international marketing emphasis on 'extreme' Korean cinema, the violence, the 'revenge', the action, as what is 'essential' about South Korean Cinema. If they aren't reading the scholarly literature, they might mistakenly call the movement the "Korean New Wave", not knowing that movement represents films from the 80's and early 90's. But of greatest concern, they might not know about the considerable impact women directors have made on New Korean Cinema. They might not know about the Lim/Byun/Jeong triumvirate. They might not know about Park Chan-ok, Bang Eun-jin, or the diasporic Korean women who have produced films in South Korea, such as Gina Kim, Kim So-yong, and Ounie Lecomte. Intentional or not, Indiewire's decision to post this false primer erases the presence of South Korean female directors of the past by failing to acknowledge their significant work. The Lim/Byun/Jeong triumvirate that helped launch New Korean Cinema haven't stopped making films. Lim's Forever the Moment (2008) was that rare sports film box office success in South Korea. Byun received a Best Director award from the industry for Helpless (2012). And Jeong's critically well-received architecture documentaries are doing considerably well at the box office for the genre. Indiewire's dismissal of female South Korean directors shows we can't rest assured that their work will be duly recognized. We have to continue the hard work of reminding folks who once knew, and introducing the work to those who never knew.

Having followed the emergence of New Korean Cinema from the beginning, when popular movie news website Indiewire posted a primer on "10 Essential Films of the Korean New Wave" (June 26, 2014) that not only didn't mention Take Care of My Cat, but dismissed female directors all together, I knew we had a problem more serious than the fact that the authors were really talking about New Korean Cinema, not the Korean New Wave. I realized that those who have come later to New Korean Cinema than those of us here at Koreanfilm.org might have gaps in their knowledge of the movement. They might take the international marketing emphasis on 'extreme' Korean cinema, the violence, the 'revenge', the action, as what is 'essential' about South Korean Cinema. If they aren't reading the scholarly literature, they might mistakenly call the movement the "Korean New Wave", not knowing that movement represents films from the 80's and early 90's. But of greatest concern, they might not know about the considerable impact women directors have made on New Korean Cinema. They might not know about the Lim/Byun/Jeong triumvirate. They might not know about Park Chan-ok, Bang Eun-jin, or the diasporic Korean women who have produced films in South Korea, such as Gina Kim, Kim So-yong, and Ounie Lecomte. Intentional or not, Indiewire's decision to post this false primer erases the presence of South Korean female directors of the past by failing to acknowledge their significant work. The Lim/Byun/Jeong triumvirate that helped launch New Korean Cinema haven't stopped making films. Lim's Forever the Moment (2008) was that rare sports film box office success in South Korea. Byun received a Best Director award from the industry for Helpless (2012). And Jeong's critically well-received architecture documentaries are doing considerably well at the box office for the genre. Indiewire's dismissal of female South Korean directors shows we can't rest assured that their work will be duly recognized. We have to continue the hard work of reminding folks who once knew, and introducing the work to those who never knew.

This is why I find institutions such as the Women's International Film Festival in Seoul (WIFFS) so important. One of my favorite South Korean film festivals, it has been shining lights on the women working in the South Korean film industry of the past and present which will provide more solid foundations for the women who will work in the industry of the future. And it was the inaugural edition of WIFFS in 1997 that renewed interest in the first South Korean film directed by a woman, The Widow, the debut and only film by Park Nam-ok.

According to information compiled by the Korean Film Archives, Park had navigated her way into the film industry while working as a newspaper reporter in Daegu. Through connections with director Yoon Yong-kyu she began working as an editor and screenwriter at the Joseon Film Studios. While working on a recruitment film during the Korean War, she met her soon to be husband, screenwriter Lee Bo-ra. After giving birth to their daughter in June of 1954, she decided to produce and direct her own film. With financial assistance from her sister, she named her new company Sister Productions.

Unfortunately, as is the case with a number of older South Korean films, (such as The Salaryman and Yangsan Province), segments of The Widow are missing sound and the entire ending is lost. In this way it's not completely clear to us how the narrative was intended to play out. What we know is that a widow with a young daughter is negotiating financial assistance from a married man. The man's wife is jealous, but that wife herself is having an affair with a younger man who uses the married woman as his sugar momma. Eventually the younger man becomes smitten with the widow and marries her, yet the widow's daughter is not receptive towards this new union and a decision is made to have friendly neighbor Mr. Song take the daughter in. Eventually the widow's new husband discovers that his true love from the past actually survived the war and his allegiances shift.

Again, that is not the whole story. This is simply a snapshot of what we are left with. The documentary of Nam, "The Dream" (Kim Jae-eui, 2001), which is included as part of the Korean Film Archive DVD on The Widow, does not fill in the final frames for us. We do learn from the documentary that the film took 6 months to make. Nam and her co-screenwriter, Jang Chang-guen, found the story's inspiration in the many war widows throughout South Korea at the time. In addition, Nam says she only had one copy of the script and lost that copy. As a result, the only documentation we now have of what happened on screen is in the ephemeral storage facility of the minds of those who watched the movie long ago.

Again, that is not the whole story. This is simply a snapshot of what we are left with. The documentary of Nam, "The Dream" (Kim Jae-eui, 2001), which is included as part of the Korean Film Archive DVD on The Widow, does not fill in the final frames for us. We do learn from the documentary that the film took 6 months to make. Nam and her co-screenwriter, Jang Chang-guen, found the story's inspiration in the many war widows throughout South Korea at the time. In addition, Nam says she only had one copy of the script and lost that copy. As a result, the only documentation we now have of what happened on screen is in the ephemeral storage facility of the minds of those who watched the movie long ago.

The Widow failed at the box office. But unlike old boys' networks where failure doesn't prohibit second, third, or more chances, Park had this one chance and never made another film. In the documentary, we see Park watching a videocassette of the film in a humble apartment on a small television set, her simple family room her screening room. "Filming one film is enough" is how Nam sees what others might identify as lack of support for women directors to proceed with future projects. Thankfully, New Korean Cinema represented a change in opportunities for women directors, but the proportion of women filmmakers in the industry still needs major improvements.

Nam's pioneering work could have been lost were it not for the research of scholars and festival programmers like the WIFFS. Their tireless work helps fill in the holes in our wider understanding of South Korean Cinema. And that work must continue if we are to thwart off the erasure, intended or not, of women from South Korean cinema's past such as the aforementioned Indiewire piece. Women were a part of the beginning of New Korean Cinema, just as they were a part of Korean Cinema's past. And if their past labor goes unrecognized, opportunity for women in the present and future industry will only be more difficult. (Adam Hartzell)

The Widow ("Mimangin"). Directed by Park Nam-ok. Screenplay by Lee Bo-ra. Starring Lee Min-ja (Lee Sin-ja), Lee Taek-gyun (Taek), Na Ae-sim (Jin), Park Yeong-sook (Lee Seong-jin's Wife), Sin Dong-hun (Lee Seong-jin, Company Owner), Lee Seong-ju (Ju, Daughter). Cinematography by Kim Young-soon. Produced by Jamae Film Production. 75 min, b&w. Released on Deceember 10, 1955.

So much of Korea's film history has been lost to us because of war and improper storage that we are thankful for even the incomplete films that are left, even one where the final scene is missing, such as Kim Ki-young's Yangsan Province. Kim's second film after his debut A Box of Death, was quite a success at the box office. Like the other successful film released before it, Chunhyang Story, Yangsan Province delved into Korea's past for a story that still resonated with the South Korea of the 50's. The film involves a love triangle between Soon-dang (Jo Yong-soo - Getmaeul), Ok-ran (Kim Sam-hwa - I Hate You, Love With An Alien), and Moo-ryong (Park Am - Madame Freedom, Salaryman). Promised to each other as husband and wife even before they were born - (Ok-ran - "What would have happened if I had been born a boy?"/Soon-dang -"Then I probably would have been born a girl") - circumstances delay Soon-dang and Ok-ran's marriage just long enough for Moo-ryong to intervene. The son of the Magistrate, Moo-ryong has grown to assume ownership of whatever he wants and has the resources to force Ok-ran into his arms. Assisting Moo-ryong in his efforts is Ok-ran's mother who despises Soon-dang's class status, but thankfully both have Ok-ran's father on his side. Eventually Moo-ryong tries to rape Ok-ran but is thwarted by Ok-ran's own defenses and the opportune arrival of Soon-dang. For Soon-dang's efforts, Moo-ryong arrests Soon-dang and chops off one of his fingers. Seeing the steps Moo-ryong will take, Ok-ran's father and Soon-dong's mother secretly wed the two lovers after Soon-dang escapes. But Moo-ryong will have none of this and sends servants to re-capture Soon-dang. I'll stop here out of respect for review ethics about revealing too much of the plot and out of confusion regarding how crazy the plot gets. Even considering the footage lost to us, the plot gets . . . uhm, ambitious.

Although the film suffers from histrionic melodramatics at times, there is much for the modern viewer to appreciate about Yangsan Province. Kim incorporates a wonderful mask dance performance, along with a nice non-mask, traditional dance and music combo that is equally lovely. Of cultural importance is the presentation of the sport of archery, which figures widely in this film for narrative effect. It's interesting since South Korean archers have been considered the top contenders in the Summer Olympics that recent South Korean cinema hasn't exploited this sport for cinematic effect as Kim does here. (Nor have we had a short track speedskating film to exploit South Korean Winter Olympics dominance.) Particularly poignant is how archery metaphors are used as double entendre when characters can't speak about sex directly. For example, Moo-ryong's father declares to Moo-ryong, "I hear you're more interested in women than in your studies up in Seoul? To which Moo-ryong responds, "No, not at all. I've just been hitting the target with my arrows." This archery as metaphor for sex (and power) comes into play later when Moo-ryong cuts off Soon-dang's finger in revenge, since Moo-ryong has cut off the finger that draws back the bowstring, Moo-ryong has effectively castrated Soon-dang.

Although the film suffers from histrionic melodramatics at times, there is much for the modern viewer to appreciate about Yangsan Province. Kim incorporates a wonderful mask dance performance, along with a nice non-mask, traditional dance and music combo that is equally lovely. Of cultural importance is the presentation of the sport of archery, which figures widely in this film for narrative effect. It's interesting since South Korean archers have been considered the top contenders in the Summer Olympics that recent South Korean cinema hasn't exploited this sport for cinematic effect as Kim does here. (Nor have we had a short track speedskating film to exploit South Korean Winter Olympics dominance.) Particularly poignant is how archery metaphors are used as double entendre when characters can't speak about sex directly. For example, Moo-ryong's father declares to Moo-ryong, "I hear you're more interested in women than in your studies up in Seoul? To which Moo-ryong responds, "No, not at all. I've just been hitting the target with my arrows." This archery as metaphor for sex (and power) comes into play later when Moo-ryong cuts off Soon-dang's finger in revenge, since Moo-ryong has cut off the finger that draws back the bowstring, Moo-ryong has effectively castrated Soon-dang.

Double entendres abound beyond the archery ones in Yangsan Province as sex is described by not being described. Kim Jong-won notes in the DVD extras (which includes a valuable interview with Kim, the actual pre-production script, and discussion of the film by Kim Jong-woon where he provides a description of the lost ending) that major differences exist between the script and the final film. This demonstrates that some decisions were made to tone down what is already a film well hung with sexual metaphors. Although there still isn't any kissing, just cheek-rubbing so frenzied one wonders if Soon-dang and Ok-ran had just dropped some Chosun version of E - you'll be surprised what Kim was still able to get away with in the dialogue here.

What Kim got away with can be extended to the mere fact that he finished this film. As he discusses on the interview included on the DVD, Yangsan Province was produced on a do-it-yourself aesthetic before DIY was cool. Well before Ryoo Seung-wan launched his Die Bad self into stardom, Kim and company were putting together a shoestring film by rummaging through the garbage of U.S. Army stations for unused film detritus and teaching the trade to anyone willing to help Kim piece together his vision.

And it is Kim's vision of that which resides in the deep dark caverns of our bodies (he was a doctor before he became a director) that most resonates when watching this film retroactively. Although the liner notes state that critics of the time expressed feelings counter to that of the many movie patrons who watched this film, (Huh Baek-nyun said it "degraded the dignity of Korean films"), Yangsan Province allows further inroads into the quirky mind of Kim Ki-young for present day critics. Kim's characters display a ruthful stubbornness to pursue what they desire, whether those desires be self-enhancing or self-defeating. Sadly, the missing scene is perhaps the best evidence of Kim's unique vision, for it is a dream sequence starkly in contrast with the realism preferred at the time. But Yangsan Province's success demonstrates that maybe South Korean audiences weren't that resistant to Kim's vision. And considering the success of his classic film The Housemaid when it was released and when it's shown at festivals today, even with missing pieces of his wider vision, we can still see that Kim was an artist of and before his time. (Adam Hartzell)

Yangsan Province ("Yangsando"). Directed by Kim Ki-young. Screenplay by Lee Tae-hwan, Kim Ki-young. Starring Kim Sam-hwa, Jo Yong-su, Kim Seung-ho, Park Am, Ko Seon-ae, Ko Seol-bong. Cinematography by Shin Hyun-ho. Produced by Sorabol Film Company. 90 min, b&w. Released on October 13, 1955.

In 1956 Korean cinema was just starting to become an industry. Han Hyeong-mo, who'd directed the spy thriller Hand of Fate in 1954, was a moving force in that process. In 1956 he made two movies, the sensational melodrama Madame Freedom and the comedy with music Hyperbola of Youth. Yes, the English title is a fair translation of the Korean. I guess it refers to two lines which curve close together but don't quite meet, though I'm not sure how it applies to this story; see for yourself.

It's a hot Saturday afternoon, and Doctor Kim (played by Park Shi-chun, a popular song composer) is trying to close Dongyoung Clinic Hospital to go out with his friend Mr. Hong. Both men wear pith helmets; Mr. Hong has an almost beatnik-ish beard on his chin, while Doctor Kim with his glasses, moustache and thinning hair rather resembles Groucho Marx. Before they can leave, they're interrupted by the arrival of a patient, a full-figured young man with stomach pains. Doctor Kim knows him well: Lee Bu-nam (Yang Hun) is a rich, spoiled fellow, son of the head of Hanmi Trade Corporation, who eats too much rich food and gets too little exercise. While a nurse takes Bu-nam off to have his stomach pumped, another patient comes in. This one is Kim Myeong-ho (Hwang Hae, Breaking the Wall), who also has stomach pains, but from not eating enough. He's a poor middle-school teacher who lives in a shack with his mother and sister. (He's quite insistent that it's a "shack" and not a "shed.") When Bu-nam returns, he recognizes Myeong-ho as an old school friend.

This gives Doctor Kim an idea. He orders the young men to change

places and live each other's lifestyle for two weeks. Reluctantly they

agree, on his assurance that it will cure them. Just before Doctor Kim

can leave the clinic, though, his three pretty nurses remind him he

still has one thing to do. He takes down the guitar that hangs by the

examination couch, and accompanies the nurses (the singing Kim

Sisters) as they sing a sprightly love song in Korean and English.

This gives Doctor Kim an idea. He orders the young men to change

places and live each other's lifestyle for two weeks. Reluctantly they

agree, on his assurance that it will cure them. Just before Doctor Kim

can leave the clinic, though, his three pretty nurses remind him he

still has one thing to do. He takes down the guitar that hangs by the

examination couch, and accompanies the nurses (the singing Kim

Sisters) as they sing a sprightly love song in Korean and English.

Bu-nam finds Myeong-ho's shack, sitting high on a hill behind the broadcasting company. It's a hard climb, and the pudgy Bu-nam is nearly exhausted when he finally sees Myeong-ho's sister Jeong-ok (Ji Hak-ja) in front of the shack. The Kims' shack has just one room, without heat, electricity, or running water. Its decorations are a print of Jesus on one wall, and a photo of Father Kim on another wall, looking boldly upwards with his fiercely waxed moustache. Jeong-ok puts Bu-nam to work splitting firewood and carrying water, hard work for a guy who on his own account "doesn't do much." When Mother (Bok Hae-suk, Hurrah for Freedom) gets home from church, they sit down to a meal of barley porridge. Theirs is a genteel poverty, a loss of station such as you might find in a Jane Austen novel. According to Jeong-ok, a lot of poor artists live in the neighborhood too: it's bohemian, not really low-class. And this is a shack, not a shed, okay?

Myeong-ho finds Bu-nam's home -- "Just look for the biggest house" on the street, Bu-nam told him -- which is decorated Western style. It looks like the set of a 1950s American situation comedy, including a piano and a home entertainment center that plays LP records. (No TV, though.) Bu-nam's sister Mi-ja (Lee Bin-hwa, The Pure Love) is as spoiled as her older brother, but younger brother Bu-yeong is one of Myeong-ho's students and welcomes him warmly. Mi-ja's rich but nerdy fiance, Choi Young-geun (Yang Seok-cheon), who drives a fancy car and wears sports clothes, but also big horn-rimmed glasses. He bores Mi-ja, who's intrigued by the poor but proud Myeong-ho, who despite his priggishnness turns out to be a dreamy dancer in the Western style. On the mattress of a Western bed in a room to himself, Myoung-ho sleeps well, while on a hillside behind the broadcasting station Bu-nam sleeps in Korean bedding on the floor, separated from Jeong-ok and her mother by a curtain dividing the shack's one room.

After two weeks of simple living Bu-nam is in better shape. He's smitten by Jeong-ok's beauty and modesty, and her sweet singing by moonlight. He helps cheerfully around the shack and even gives up his imported Pall Malls for Korean cigarettes. Bu-nam invites Jeong-ok to go to the beach with him, patiently riding the train there. (Hyperbola of Youth is set in Busan, near the ocean, with some nice location shots.) Mi-ja is struck by Myeong-ho's integrity and smooth dancing. Myeong-ho courts her by delivering evangelical sermons -- "Mi-ja, you must change everything about your life!", which she then repeats to her fiance -- but Myeong-ho still goes with her to the beach, riding in the Lee family motorboat and teaching Mi-ja to swim without mussing her hair.

Will their families accept their marriage? Myeong-ho's mother distrusts rich young men who make grand promises to poor young women, and Mi-ja's father, who arranged the engagement with Young-geun, will hardly welcome her liaison with a starving middle-school teacher. But love and resourcefulness, with the help of Doctor Kim, win out in the end.

In style, Hyperbola of Youth belongs more to the 1930s than to the 1950s, but that's okay -- Thirties Hollywood comedies are more fun. The premise is a "Skinny and Fatty" story, a kind that Yang Hun had made before his appearance here, and would do again (often with Yang Seok-cheon) throughout the 1950s. The songs, most of them written by Park Shi-chun, don't advance the plot; as usual in older musicals, the various characters simply feel like bursting into song, and do so. The Kim Sisters sing in the clinic; Jeong-ok sings her longing for love under a willow tree by moonlight, unaware that Bu-nam is listening to her fondly. Early in the film an A-frame coolie, played by the popular singer Kim Hee-gap, simply stops by the shack and sings a medley of golden oldies for Jeong-ok. The movie's ambivalence about wealth and ostentation, while very Korean, is also similar to Hollywood movies from the Thirties. Think of My Man Godfrey (Gregory LaCava, 1936), whose title character (William Powell), ruined by the 1929 crash, lives for a time on Skid Row, then is adopted by a spoiled rich girl (Carole Lombard) and puts his life back together. Hyperbola of Youth is much simpler and more direct, but very good-natured and entertaining. (Duncan Mitchel)

Hyperbola of Youth ("Cheongchun-ssanggokseon"). Alternate title: "Double Curve of Youth". Directed by Han Hyeong-mo. Screenplay by Kim So-dong. Starring Hwang Hae, Ji Hak-ja, Lee Bin-hwa, Yang Hoon, Yang Seok-cheon, Bok Hae-suk, Kim Hee-gap, the Kim Sisters, Park Shi-chun. Cinematography by Lee Seong-hwi. Produced by Han Hyeong-mo Productions. 100 min, b&w. Released on April 10, 1956.

Madame Freedom was released in 1956, the year Peyton Place was published in the United States, which seems fitting. Based on a novel of the same name serialized in a Seoul newspaper, the movie was both controversial and popular, inspiring a series of sequels and remakes, the latest in 1990. Three years after the Korean civil war South Korean society was struggling economically, and Western culture was making more inroads. In particular, there was an underground craze for Western-style dancing, with its titillating format of partners embracing. The police raided dance clubs regularly, and the novel capitalized on the headlines. The allure of Western dancing and Western luxury goods provided the framework for Madame Freedom.

Oh Sun-young (Kim Jung-rim) lives with her husband, Professor Jang Tae-yoon (Park Am), and their young son Kyoung-soo. Shin Choon-ho (Lee Min), a university student who lodges next door, is a bit wild: he likes to play jazz records loudly enough to disturb father and son from their studies. It's not clear whether Sun-young minds the music. She seems pleased when Choon-ho says flirtatiously that he'll turn off the music only when she demands it.

Sun-young's marriage is already pretty "modern": they live in their own walled house, not with Professor Jang's parents, so Sun-young has no mother-in-law to rule her life. It may even have been a love match, instead of an arranged marriage: a friend teases her, early in the film, for living with her "beloved," as opposed to the unromantic husbands of most wives.

Sun-young's marriage is already pretty "modern": they live in their own walled house, not with Professor Jang's parents, so Sun-young has no mother-in-law to rule her life. It may even have been a love match, instead of an arranged marriage: a friend teases her, early in the film, for living with her "beloved," as opposed to the unromantic husbands of most wives.

Sun-young takes a job managing a shop called "Paris", which sells Western cosmetics and accessories. Her husband consents reluctantly, because they need the money; as in the West, professors have high status but not big paychecks. Her boss's husband, a businessman named Han Tae-suk (Kim Dong-won), has a roving eye that has settled for the moment on Sun-young. She is also drawn into a club of well-to-do wives, who are interested in Western dancing, flaunting their expensive jewelry, and making their own money. A dance party is being organized for the members, as long as their dance partners are not their husbands.

Professor Jang is moonlighting too. His former student Miss Park Eun-hee (Yang Mee-hee), working in a Westerner's office, has asked him to teach Korean grammar to her fellow typists. He accepts no money for the course, perhaps because he enjoys walking Miss Park home each evening.

In the film's major set piece, Sun-young lets Choon-ho take her to a dance hall, where Park Joo-geun and his Orchestra are playing the mambo, and a woman dancer (Na Bok-hee) in a tight black dress with a spiral of white fringe tries to shimmy like your sister Kate. From the corner table where she sits with Choon-ho, Sun-young watches with rapt fascination, much as the movie's original audience must have done. The whole sequence -- the orchestra, the dancer, the couples on the dance floor -- is framed for the theatre audience, not for Sun-young. When Sun-young is alone for a moment, Han Tae-suk notices her and asks her to dance.

After all this, it's no surprise to find Sun-young trading her hanbok for Western clothes. When Choon-ho dumps her, she asks Han to be her partner at the upcoming dance party. As poor Kyoung-soo studies at home alone, his parents cavort with their paramours. Waiting for a rendezvous with Han, Sun-young encounters her husband walking with Miss Park, and upbraids him for his infidelity with the righteous fury of the guilty. At work, she learns that a customer hasn't paid for an expensive purse he ordered, and the film moves inexorably to its tragic but ambiguous ending.

Han Hyeong-mo's Madame Freedom is as campy as any vintage melodrama from the West, though Western viewers may be struck by what looks to us like great erotic restraint: neither Sun-young nor her husband actually consummate their adulterous flirtations, though Sun-young comes closer. Sun-young and Han kiss fleetingly on the lips, as their embrace carries them out of the frame -- at which point their tryst is interrupted. The same device (embrace, rub cheeks, move out of frame) is used to this day in Korean TV melodramas. Even hip sketch comedy on TV can evoke squeals by showing a man and woman nibbling opposite ends of a noodle until their lips _almost_ touch, and in the enormously popular comedy My Sassy Girl (2001), the young lovers never kiss, let alone have sex.

It's also fun to watch the use of English words and phrases in Madame Freedom. Choon-ho especially sprinkles his conversation with English, as English speakers used to use French: to suggest worldliness, sophistication ... and romance. "I love you," Choon-ho tells Sun-young in English, his eyes liquid with insincerity. He's such a player, you have to love him. By contrast Han Tae-suk must be one of the less likely romantic figures in cinema with his bald head and weak grin. When he and Sun-young tease back and forth over whether he will be her "substitute" boyfriend or the real thing, it's like watching two sixth-graders trying puppy love on for size.

On the other hand, Madame Freedom's women differ from their counterparts in Western melodrama. The sexual double standard is firmly in place, though Miss Park's aggressive pursuit of Professor Jang has no consequences for her, and Sun-young's offense lies in violating her purity as a mother more than as a wife. The women's wish to have their own money, however, isn't seen as a bad thing. I bet Korean wives enjoyed watching Sun-young's boss, a successful businesswoman in her own right, keep her philandering husband Han Tae-suk on a short leash; and when one of the club members shows off the three-carat diamond on her finger, many of them would have taken it as a challenge. Diamonds, not husbands or boyfriends, are a wife's best friend. (Duncan Mitchel)

Madame Freedom ("Jayu-buin"). Directed by Han Hyeong-mo. Screenplay by Kim Seong-min and Lee Cheong-gi. Starring Kim Jeong-rim, Park Am, Lee Min, Noh Kyung-hee, Yang Mee-hee, Kim Dong-won, Joo Seon-tae, Ko Hyang-mi, An Na-young. Cinematography by Lee Seong-hwi. Produced by Samsung Film Co. 125 min, b&w. Released on June 9, 1956.

Lee Byeong-il's The Wedding Day was a breakthrough for Korean cinema. It not only did well at home, winning critical praise for its comedy and high moral values, it also won an award for Best Comedy at the Fourth Asian Film Festival, thus beginning Korean cinema's emergence to international audiences.

I could never quite get a fix on the comedy in The Wedding Day. Some of what struck me as funny was probably not intended to be. The portentous orchestral music over the opening credits (played, we are solemnly informed, by a special appearance of the KBS orchestra) at first sounds ominous and melodramatic, then turns into a Stephen Foster tune about happy peasants serving their yangban masters. The opening scene has a very churchy female chorale chirping over the young heroine and her entourage. If The Wedding Day hadn't been made in 1956, I'd have started laughing then, taking it for a satire of yangban pretensions and of modern Korean nostalgia. (Once Upon a Time on the Battlefield shows how well that can be done.) But no: the target of the humor is upstart yangban wannabe's who try to rise above their station, and get put firmly in their place.

The story begins with Maeng Jin-sa's return from the Bellflower Valley, where he has just negotiated a marriage between his daughter Gap-bun (Kim Yoo-hee) and Mi-eon, son of Kim Pan-seo. He was so excited by the granaries, the imposing mansion, and the many servants,

that he neglected to actually see the prospective bridegroom. On hearing this, Jin-sa's uncle, who is evidently the brains of the family, stalks out in disgust.

The story begins with Maeng Jin-sa's return from the Bellflower Valley, where he has just negotiated a marriage between his daughter Gap-bun (Kim Yoo-hee) and Mi-eon, son of Kim Pan-seo. He was so excited by the granaries, the imposing mansion, and the many servants,

that he neglected to actually see the prospective bridegroom. On hearing this, Jin-sa's uncle, who is evidently the brains of the family, stalks out in disgust.

Jin-sa is played by Kim Seung-ho (The Coachman, Romance Papa), and his performance here is anything but subtle, with lots of goggle-eyed, open-mouthed mugging. When a wandering scholar spends the night with the Maeng family, he mentions casually that Kim Pan-seo's son is lame, with one leg shorter than the other. This news throws Jin-sa into a tizzy: how can he give his dear Gap-bun, a girl raised with the utmost care, to a cripple? Gap-bun is no happier, ignoring the protestations of her maidservant Ip-bun (Cho Mi-ryung) that maybe Mi-eon is a nice man, and surely he's suffered a great deal. Gap-bun, we see, is her father's daughter. But it's hard to be sure about Ip-bun's motives. She had expected to accompany Gap-bun to her new home, which incidentally would get her away from the servant Sam-dol (Hwang Nam), who wants to marry her, but whom Ip-bun considers beneath her. Ip-bun is hardly inclined to discourage Gap-bun's nuptials, her ticket out of the bumpkin-ish Maeng household.

Maeng Jin-sa decides to send Gap-bun away to stay with relatives, substituting Ip-bun at the wedding. Ip-bun is torn: on one hand she will move away and escape marriage to Sam-dol, but on the other she's being used to deceive a man whom she pities for his disability, without ever having met him. When Mi-eon arrives for the wedding, however, he turns out to be perfectly able-bodied, gracefully spoken, and fair of countenance; the rumor of his disability was a trick to test the virtue of the Maeng clan. Quick! Send Sam-dol to fetch Gap-bun! Will she be able to return in time? Or will she lose this gorgeous hunk of man to a mere servant girl?

Myself, I don't believe in aristocracy or royalty -- not because I'm an American; millions of Americans worshipped Princess Diana, after all! -- and I wouldn't trust a noble bridegroom who tested a prospective bride the way Kim Mi-eon does. (Such tests are a staple of European no less than Korean folklore.) Be careful what you wish for, I'd warn the bride: you may get it. So I don't get the feeling of healthy moral satisfaction from The Wedding Day's ending that the filmmakers intended. I picture Mi-eon a few years down the road with two or three concubines and large gambling debts, which isn't my Western cynicism but another time-honored folkloric touch that belongs to stories of this type.

The Wedding Day looks better than other Korean films I've seen from 1956; no doubt its international success ensured that it would be preserved with more care than throwaway comedies like Hyperbola of Youth. Lee Byeong-il, who studied film at UCLA in the late 1940s, directed in a professional, unadventurous style. The result feels like a National Geographic travelogue of old Korea, with lots of pretty girls, servants, ladies and gentlemen in quaint period costume. Its historical importance in Korean cinema is secure, and if you like a straightforward fable of old-time folkways, The Wedding Day will suit you fine. (Duncan Mitchel)

The Wedding Day ("Sijip-ganeun nal"). Directed by Lee Byung-il. Screenplay by Oh Young-jin. Starring Jo Mi-ryung, Kim Seung-ho, Choi Hyun, Kim Yoo-hee, Song Hae-cheon, Seo Wol-young, Seok Geum-seong, Ha Ji-man, Hwang Nam. Cinematography by Im Byung-ho. Produced by Donga Film Co. 70 min, b&w. Released on November 27, 1956.

Bong-su is a farmer who, even in a good year, is unable to pay back his debts and properly support his family (a wife, a daughter, and a son who has just returned from the army). His problem is not that he doesn't work hard (he does), but that farming doesn't pay well, and he lacks the cunning to maintain or increase his wealth. Playing cards at the local tavern or trying to arrange business deals in Seoul, he is gradually pulled towards ruin through fault of his honest and naive nature.

Based on a play by Son Ki-hyun, Money can be seen as a strident (if slightly simplistic) critique of capitalist society, and a sign of the influence that Italian Neorealist cinema had on postwar Korean film. In 1958, the film's pessimistic tone must have served as cathartic release for many frustrated viewers, with so much of the country facing similar hardships to the main characters. Today, the film is perhaps best remembered for its memorable performance by actor Kim Seung-ho as the farmer, who would later make a similarly strong impression in works like The Coachman and Mr. Park.

Based on a play by Son Ki-hyun, Money can be seen as a strident (if slightly simplistic) critique of capitalist society, and a sign of the influence that Italian Neorealist cinema had on postwar Korean film. In 1958, the film's pessimistic tone must have served as cathartic release for many frustrated viewers, with so much of the country facing similar hardships to the main characters. Today, the film is perhaps best remembered for its memorable performance by actor Kim Seung-ho as the farmer, who would later make a similarly strong impression in works like The Coachman and Mr. Park.

Director Kim So-dong is likely to have had few resources available to him when shooting this feature. Film stock was expensive and hard to come by in this era, and several jarring cuts we see can probably be explained by the fact that re-shooting a scene several times to make it come out just right was not an option. Nonetheless, the film is handsomely and creatively lit, and the print I saw at a Korean Film Archive screening was of surprisingly good quality -- much better than the image reproduced here.

Kim adopts an unhurried pace to tell his story, and his tendency to move the camera up close into the actor's space heightens the intimacy we feel for the characters. He often shoots his actors speaking straight ahead into the camera, which in this case makes them appear more vulnerable. He also employs a creative use of sound in one key moment when the farmer learns that he has been swindled: as he sits stunned in his country home, sounds of the city suddenly engulf the soundtrack.

Some of the film's most engaging moments are the slow, drawn-out sequences when Bong-su is cheated out of his hard-earned cash. There's a perverse sort of pleasure in watching the crooks at work: even though we recoil at what they do, they have a smooth, devilish charm about them. In the end, however, fate proves to be much more cruel than any of the film's human characters. The chance events that lead to our poor farmer's downfall feel nothing short of sadistic.

Shortly after its release, Money was selected for submission to the Asia Pacific Film Festival, but then withdrawn at the last minute by the government because its themes were too dark. (They substituted Han Hyeong-mo's comedy Hyperbola of Youth, another interesting work, though of a much different style.) The film community protested on Kim So-dong's behalf, but to no avail, and this remarkable film missed out on its best chance of reaching international audiences. (Darcy Paquet)

Money ("Don"). Written and directed by Kim So-dong. Starring Kim Seung-ho, Choi Nam-hyun, Choi Eun-hee, Kim Jin-gyu, Jeong Ae-ran, Hwang Jeong-soon, Im Yang, Jeong Min. Cinematography by Shim Jae-heung. Produced by Kim Productions. 123 min, b&w. Released on March 9, 1958.

Shin Sang-ok's 1958 classic A Flower in Hell opens with what is basically documentary footage of daily life in postwar 1950s Seoul. Shots of U.S. soldiers in particular predominate among these images -- this was an era when Korean society was desperately poor, and one of the few ways to secure a decent living was to forge some kind of relationship with the U.S. army and its soldiers, who carried hard currency.

The petty criminal Young-shik (played by Kim Hak) is one such example; he earns cash by stealing supplies from the U.S. army base and re-selling them on the black market. He lives with his girlfriend, a prostitute who calls herself Sonya and who caters especially to American soldiers. A classic femme fatale figure, Sonya is played with daring abandon by Shin Sang-ok's wife, the acclaimed actress Choi Eun-hee.

The petty criminal Young-shik (played by Kim Hak) is one such example; he earns cash by stealing supplies from the U.S. army base and re-selling them on the black market. He lives with his girlfriend, a prostitute who calls herself Sonya and who caters especially to American soldiers. A classic femme fatale figure, Sonya is played with daring abandon by Shin Sang-ok's wife, the acclaimed actress Choi Eun-hee.

However A Flower in Hell is told primarily through the eyes of Dong-shik (Jo Hae-won), the pure-minded and naive younger brother of Young-shik who travels from the country up to Seoul in order to find his brother. Hoping to convince him to return to his hometown (and a morally upright lifestyle), Dong-shik moves in with Young-shik. Nonetheless, his entreaties fall on deaf ears, at the same time as he starts to be seduced by the worldly Sonya.

Few Korean films of this era present the hard realities of day-to-day existence with such honest force as A Flower in Hell. The focus on the lower classes, and on the sexual trade between U.S. soldiers and Korean prostitutes (such women were often derogatively referred to as "Western princesses"), makes for an eye-opening topic even today. The depiction of Sonya in particular is fascinating; she comes across as predatory and dangerous, but also self-confident, highly competent and alluring. Viewers of the day, who were used to seeing Choi Eun-hee as a pure-hearted, demure woman both on and offscreen, were reportedly shocked and uncomfortable to see her in this role.

A Flower in Hell also represents Shin Sang-ok at the top of his form as an aesthetic filmmaker, despite the technical hurdles he faced (reportedly the borrowed Arri camera kept breaking during the shoot). Although the entire film is suffused with energy and momentum, two sequences in particular stand out for their audacity. Midway through the film, Young-shik orchestrates a daring theft of materials from the U.S. army base as the soldiers are being entertained by a group of dancers. The erotically-charged performance (shot in a real life setting), intercut with shots of the theft being carried out, make for a tense and memorable scene.

Yet it is the penultimate scene, a extended life-and-death struggle that spills onto a vast field of mud, that justifiably remains the most famous. It is both a striking blend of sound and image, as the two mud-covered figures grapple in seeming slow motion, and also a suspense-filled nail-biter as we wait to see the final outcome. No other Korean film of this era contains a scene that is so viscerally striking, and which continues to feel so modern. (Darcy Paquet)

A Flower in Hell ("Jiokhwa"). Directed by Shin Sang-ok. Screenplay by Lee Jeong-seon. Starring Choi Eun-hee, Kim Hak, Jo Hae-won, Gang Seon-hee. Cinematography by Kang Beom-gu. Produced by Seoul Film Company. 86 min, b&w. Released on April 20, 1958. Winner of a Best Actress award for Choi Eun-hee at the 2nd Buil Film Awards.

![]() A College Woman's Confession (1958)

A College Woman's Confession (1958)

Choi So-young is a university student majoring in law, whose studies are supported by her grandmother. However after her grandmother dies, and with no parents or other relatives to support her, she is faced with the prospect of abandoning her career dreams and dropping out of school. With her rent overdue, So-young looks for a job, but finds that the only men willing to hire her are interested in favors that extend beyond the workplace.

Meanwhile So-young has a friend, the aspiring novelist Hee-sook, who has stumbled across a rather unusual diary written by a young woman who has recently died. The diary reveals that a powerful politician named Choi Rim has a lost biological daughter, born to a woman he knew in the years before his marriage. But Assemblyman Choi has no knowledge of his daughter's existence or whereabouts.

Hee-sook, with a novelist's appreciation for dramatic plot turns, suggests something that So-young would never consider on her own: posing as the daughter of Assemblyman Choi in order to put herself through college. So-young rejects it out of hand, but as time passes and she becomes more desperate, it starts to seem like a more attractive option.

Hee-sook, with a novelist's appreciation for dramatic plot turns, suggests something that So-young would never consider on her own: posing as the daughter of Assemblyman Choi in order to put herself through college. So-young rejects it out of hand, but as time passes and she becomes more desperate, it starts to seem like a more attractive option.

A College Woman's Confession is Shin Sang-ok's big hit of the 1950s, and indeed the film that established his commercial career. Reportedly based on a French feature which was released in Korea with the title Betrayal (I haven't been able to identify it), Shin's film is notable for the star-making performance of Choi Eun-hee as So-young, and for its focus on the challenges faced by women in the post-war era. It's not hard to see why the film was so popular with female audiences of its time, given its dramatic strengths and the highly unusual portrait of a talented female lawyer who commits herself to defending disenfranchised women, even as she herself is in danger of losing everything.

Cinematically, Confession contains accomplished acting, effective use of suspense (despite the slow manner in which it unfolds), and a keen feel for image and sound during an era when technical challenges dominated the filmmaking process. (Less effective is the film's musical soundtrack, with its sudden bursts of dramatic music that may seem comical to contemporary audiences.) I found myself especially taken with the performance of Kim Seung-ho as Assemblyman Choi, whose measured, softly-delivered speech and deliberate manner overlay a passionate devotion to his newfound daughter.

There is also an interesting, long flashback that occurs in the latter part of the film, about a woman defended by So-young who has been accused of murder. The defendant is played by well-known actress Hwang Jeong-soon, who together with Choi won an acting award at the first edition of the short-lived Domestic Film Awards in 1959. We see in the defendant's story parallels to So-young's own experience, despite the vast divergence in their fates. The film's sudden return to the grim realities of poverty in the midst of So-young's professional advancement serves to place an asterisk next to her story, reminding us of what most people of that era were experiencing. (Darcy Paquet)

A College Woman's Confession ("Eoneu yeodaesaeng-ui gobaek"). Directed by Shin Sang-ok. Screenplay by Shin Sang-ok and Jo Nam-sa. Starring Choi Eun-hee (So-young), Kim Seung-ho (Assemblyman Choi), Yu Gye-seon (Choi's wife), Choi Hyun (Choi's assistant), Kim Sook-il (Hee-sook), Hwang Jeong-soon (defendant). Cinematography by Kang Beom-gu. Produced by Seoul Film Company. 120 min, b&w. Released on July 12, 1958.

The Nam family leads a life of upper-middle class luxury. Supported by the medical practice of Dr. Nam, the family patriarch, sisters Jung-hee and Myung-hee and their kid brother Chang-sik live in a spacious home, wear fancy Western clothes, and enjoy leisure activities. (The mother is absent.) The people they associate with are also wealthy, such as Chairman Pang for example, who we see arriving in a Korean Air jet and being met on the airport runway by a limousine at the start of the film.