A Conversation with Shin Sang-okk

by Adrien Gombeaud

Shin Sang-okk was born in 1925 in Ch'ongjin ( Hamyong Province, now in North Korea ). His life reads like a real movie script. He studied painting at the University of Tokyo before becoming a director in Korea. His career is one of the longest in the history of Korean cinema : he has shot about 120 films. In 1978 he was kidnapped with his wife, star Ch'oe Eun-hui and taken to North Korea. He shot 5 movies at Pyongyang Studio before escaping. He then went to Hollywood where he became a successful producer. He now lives and works in Seoul.

Shin Sang-okk is often asked about his stay in North Korea, so I decided to focus mainly on the biggest part of his life: his life as a director and his ideas on film aesthetics.

Adrien Gombeaud : What are your first film memories?

Shin Sang-okk : When I was just a kid I saw many films. Even films that I was not supposed to see at that age! Movies by Chaplin and Eisenstein of course. But I also had the opportunity to see many Korean films, films that very few people have seen because they were destroyed during the war. I think there were only a few artistic directors at that time. I was very moved by Na Un-gyu's "Arirang", Korea at that time was just producing a few films a year. Later when I started studying art in Japan, I realized this vacuum in our cinema and decided to come back to Korea to rebuild Korean national cinema. I worked in the Japanese film industry to learn the techniques and then came back to Korea.

AG : Before we move on to your career as a director I'd like to speak about your work as a painter. What kind of paintings were you doing? Traditional Oriental painting or Western painting?

SS : I was doing Western painting. Mostly because at that time the public was more interested in Western paintings than in traditional paintings. Also I must say that Western painting is closer to cinema than Eastern painting; you have close-ups, deep fields -- Eastern painting is more "faded" as we say. So I think that as a painter I already had a film director's vocation. Western painting was a way to make movies with no technical or economical problems. But even though I was painting in the Western way, it was a detour to go back to Korea's culture and way of thinking.

SS : I was doing Western painting. Mostly because at that time the public was more interested in Western paintings than in traditional paintings. Also I must say that Western painting is closer to cinema than Eastern painting; you have close-ups, deep fields -- Eastern painting is more "faded" as we say. So I think that as a painter I already had a film director's vocation. Western painting was a way to make movies with no technical or economical problems. But even though I was painting in the Western way, it was a detour to go back to Korea's culture and way of thinking.

You know that the beauty of Eastern painting is the beauty of emptiness, of what is "not seen". And this is what I try to do in my films as a director. Of course it's not easy to show emptiness in a film, you can't just not paint the screen, leave it white like they do in ink paintings! The way I do it is by working on symmetry and dissymmetry. When I do composition, I usually don't try to look for a perfect balance. I like to have one part of the frame filled and let another part stay empty. This is also why I like to isolate the actors in doors or windows in one part of the frame. I create emptiness by using dissymmetry. These are ideas that I had by practicing painting in my early years. Also it's interesting to notice that Western painting and cinema arrived at the same period of time in Korea. It was a major shock. Cinema changed our way of seeing the world around us, and I think it was ahead of our society.

AG : You always say that the 60's were your golden years, but most Koreans didn't enjoy this decade very much...

SS : Yes, it was a very hard period of time for most Koreans because the country was still poor. But they were the golden years of Korean cinema. In the 60's we had more freedom of speech than in the 70's. With time dictatorship became more and more oppressive. My movies were successful because they described the reality of our situation and the difficulty people had in living. Take the "Yonsan Gun" saga for example [photo above]. The film is divided into two episodes and lasts in total 5 hours and 30 minutes. During the film, King Yonsan becomes more and more violent. It was my second film in color, a very big production. Actually through an expensive historical movie I was speaking about the present days, and about the political situation of Korea. This is why King Yonsan is such a realistic character, he was in fact -- alive! Under the military regime people could relate to what was happening in this movie and that's why they wanted to see it. It was the case for many of my films in the 60's.

AG : In your movies, even the early ones, there is always an erotic touch. Today many Korean directors shoot sex scenes. Do you think that you sort of invented eroticism in Korean cinema?

SS : Yes, you could say that because in 1958 I directed "Flowers of Hell" ['Chiokhwa' in Korean] and I was the first one to show a kiss on screen. I had to deal with the censorship because of that -- that also must have changed people's minds in a way. [Please note that it has recently been established that Han Hyeong-mo's The Hand of Fate from 1954 is Korea's first oncreen kiss. -ed]

AG : But isn't it strange that you call yourself at the same time a Confucian director and the inventor of Korean eroticism on screen?

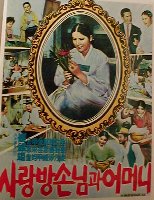

SS : Yes I know it sounds strange, but that's what I did anyway! [laughs]. Sometimes I also used eroticism to talk about Confucianism, you know. Just like what I was saying about the emptiness in the composition: it's very much a question of contrast. For example in "The Houseguest and My Mother" [photo on right] the maid is a very frivolous girl, so the woman looks even more Confucian.

SS : Yes I know it sounds strange, but that's what I did anyway! [laughs]. Sometimes I also used eroticism to talk about Confucianism, you know. Just like what I was saying about the emptiness in the composition: it's very much a question of contrast. For example in "The Houseguest and My Mother" [photo on right] the maid is a very frivolous girl, so the woman looks even more Confucian.

Actress Kang Su-youn enters into the lobby of the hotel and sits next to Shin Sang-okk.

Kang Su-youn : At that time Korea was not very open-minded, and to express a character's eroticism or even talk about sexuality was impossible. Shin Sang-okk sort of opened a door and he's been the only one to talk about such things for a long time. He was a pioneer, and who knows : I might not have portrayed the character I play in "Girls' Night Out," for example, without Shin Sang-okk's films!

Shin Sang-ok : Well it hasn't been such a straight story, as I said the regime became more oppressive in the 70's and eroticism almost disappeared for one decade before reappearing today in brilliant films like "Girls' Night Out" or even in "Lies". But we had to wait until the end of Park Chong-hui's military dictatorship before Korean cinema was really reborn.

AG : After your stay in North Korea you spent most of the 80's working in Hollywood as a producer, but you never directed a film there yourself. Why?

SS : I suddenly, and I must say brutally, realized the cultural differences between our two civilizations. I felt very far away. Even today when I travel with my movies in festivals and when I meet foreign people who are interested in them, I sometimes think that this might just be a big misunderstanding. For example I'm always at the same time surprised and pleased that non-Koreans appreciate "The Houseguest and My Mother". But then I think that there must be something universal in every movie.

PARIS October 1999

NOTES : "Yonsan Gun" was directed by Shin Sang-okk in 1961, and it deals with one of the most obscure Korean kings: Yonsan. He reigned over Korea between 1494 and 1505. Obsessed by the murder of his mother when he was just a kid, he became paranoid. He organized purges of the well-read and a terrible book burning. He also transformed a temple into a school for Kisaeng. He personally raped many women and murdered many people in the court. In 1987, Im Kwon-taek also directed a very good film about King Yonsan called "Yonsan Ilgi".