2007 Puchon International Fantastic Film Festival

by Kyu Hyun Kim and Adam Hartzell

For Eternal Hearts, dir. Hwang Qu-dok (Opening Film)

Our last festival report from the Puchon International Fantastic Film Festival came in 2004, which in retrospect was the end of an era. Sixth months after the conclusion of the event, popular festival director Kim Hong-joon was relieved of his position and two years of political infighting, boycotts, and turmoil followed. Only in this year's edition did PiFan start to feel like a "normal" festival again: attendance was up, and the focus had returned to the films and the guests. The third new festival director in three years, Han Sang-jun, is well-liked and appears to have the support of the Korean film community.

One of the benefits of stability is that PiFan can now re-focus its efforts on establishing its own identity. In calling itself a "fantastic" film festival, Puchon follows a tradition started by a group of festivals in Europe (including Sitges, Fantasporto, Brussels, etc) that concentrate on horror, sci-fi, fantasy, and other related genres. At the same time, PiFan tries to cater to the local community, which for the most part seems to be interested in family-centered fare. Japanese films of all genres also tend to be highly popular among younger viewers who ride the subway out from Seoul. The result? Programming at this event can sometimes seem a bit contradictory and uneven, but most often everyone finds something in the program that they are interested in watching.

* Note that in addition to the reports below, some more comments about this year's edition can be found at Tom Giammarco's blog, Seen in Jeonju.

Kyu Hyun: Report #1

Puchon Film Festival has successfully rebounded from its conflict with the city government last year, with then-Festival Director Lee Jang-ho managing to perform a difficult balancing act between the demands and expectations of the vocal fans of the extreme fantasy/SF/horror genre and those who prefer mainstream, family-friendly fare. The general impression of the PiFan 2007, in its 11th year and put together under the supervision of FD Han Sang-joon and programmers Kwon Yong-min and Jin Park, is one of moderation. The number of films has been scaled down to approximately 215 from last year's 230 plus, but the creature-building workshops, guest talks, and most importantly the careful balancing act between the aggressive, the gory and the outrageous on the one hand and the cute, the genteel and the acceptable-for-elementary-school-children on the

other have been retained, exemplified by this year's special program showcasing so-offensive-it's-funny antics of Herman Yau's Hong Kong opuses (Ebola Syndrome, Gong Tau and, of course, The Untold Story) and the Richard Fleischer retrospective starring the square-jawed (could any living human being be possibly more square-jawed than a young Kirk Douglas?) Kirk Douglas (20,000 Leagues Under the Sea and The Vikings: what, no Conan the Destroyer?). Ah, of course, there is the PiFan regular Dario Argento, (Phantom of the Opera? Oh dear) but other favorites Miike Takashi and Kurosawa Kiyoshi are MIA this year. Perhaps for the Korean cinephiles the most surprising and highly-anticipated retrospective might be the hybrid genre films of Monte Hellman: Cockfighter, Two Lane Backdrop, Back Door to Hell, Ride in the Whirlwind, and The Shooting (pictured), one of those mysterious and unnerving Westerns, like Clint Eastwood's High Plains Drifter, pregnant with hints of the supernatural.

other have been retained, exemplified by this year's special program showcasing so-offensive-it's-funny antics of Herman Yau's Hong Kong opuses (Ebola Syndrome, Gong Tau and, of course, The Untold Story) and the Richard Fleischer retrospective starring the square-jawed (could any living human being be possibly more square-jawed than a young Kirk Douglas?) Kirk Douglas (20,000 Leagues Under the Sea and The Vikings: what, no Conan the Destroyer?). Ah, of course, there is the PiFan regular Dario Argento, (Phantom of the Opera? Oh dear) but other favorites Miike Takashi and Kurosawa Kiyoshi are MIA this year. Perhaps for the Korean cinephiles the most surprising and highly-anticipated retrospective might be the hybrid genre films of Monte Hellman: Cockfighter, Two Lane Backdrop, Back Door to Hell, Ride in the Whirlwind, and The Shooting (pictured), one of those mysterious and unnerving Westerns, like Clint Eastwood's High Plains Drifter, pregnant with hints of the supernatural.

Korean cinema is not doing so well in comparison. Jang Jin's My Son and For Eternal Hearts, the older-generation hitmaker Hwang Gyu-duk (who now spells his name Hwang Qu Dok)'s newest film in thirteen years, lead a slew of independent films, some of which barely qualify as fantasy, let alone horror or science fiction. I am definitely not the only guest who is wondering why PiFan refuses to (or is unable to, as the case may be) provide showcases for the Korean horror/fantasy films of the late summer and early Fall seasons. I mean, why is Cinderella, already released in Region 1 DVD stateside by Tartan USA, the only Korean horror film shown in this year's PiFan? Something's definitely not right.

For two years in the row PiFan suffered from the absolutely crummy quality of low-budget Japanese selections (last year's atrocity entitled Mail, starring Kuriyama Chiaki, may well be the very worst film I have ever seen in a film festival), so I avoided much of the Japanese selections. Sorry, I am not really psyched to watch a Japanese movie entitled "F*ckin' Runaway" starring a suicidal 21-year-old boy (seeing the word "f*ck" in the titles of Japanese cultural products is always embarrassing, like a nerd wearing a huge cod-piece in his pants to impress girls in a party) or "Ghost vs. Alien." Hey, for all I know, these films might be earth-shaking masterpieces, and some scenes from them might be quoted in the next Quentin Tarantino

film, but please, let you be the person to discover that. Thank God the great Nagai Go is around to introduce Cutie Honey, sadly one of very few truly successful non-anime films adapted from Japan's classic comics. Chotto-sa, nantoka naranai?

film, but please, let you be the person to discover that. Thank God the great Nagai Go is around to introduce Cutie Honey, sadly one of very few truly successful non-anime films adapted from Japan's classic comics. Chotto-sa, nantoka naranai?

Rounding out the selections are strong representations from Iberian, Scandinavian and Southeast Asian regions: again, little surprise there. And lest we forget, just to remind us that not only Hollywood cinema but American TV dramas are out to conquer the universe, Masters of Horror Season 2 is here to throw its weight around, with the red carpet rolled out to the series creator Mick Garris, who, along with the Variety reviewer Derek Elley and Japanese director Sono Sion, will serve as judges for the feature film competition.

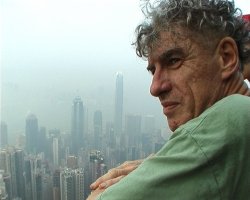

Having missed the opening ceremony and screening of For Eternal Hearts, (I freely confess that I was badly burned by last year's interminable ceremony that went over the schedule by two hours) I attended the screening of In the Mood for Doyle (a free-form video essay on Hong Kong-based cinematographer Christopher Doyle) and The Angry Men of Korean Cinema, directed by Yves Montmayeur on July 13. Following the screening was a panel with Montmayeur, Korean directors Park Chan-wook, Ryu Seung-wan and Min Gyu-dong, moderated by Film 2.0's Kim Young-jin.

In the Mood for Doyle is by far the more interesting of the two. Beginning with Gus Van Sant's observation that Chris Doyle is a "beatnik," a Jack Kerouac who made his home in East Asia, Montmayeur follows Doyle around as the latter wanders around back streets of Hong Kong, usually slightly inebriated yet displaying sharp faculties of

observation, enthusiastically blurting out "Wow, wow" at anything that strikes his fancy. Doyle himself is such a charming subject, the seemingly focus-less format of the docu works pretty well. Disappointingly, Wong Kar-wai, Fruit Chan, Peter Ho-san Chan and other Hong Kong filmmakers don't give us a whole lot of insight about what they get out of their collaborations with the cinematographer, although the docu accurately captures the absolutely cramped, claustrophobic environment these filmmakers work in (sort of going against the obvious intention behind the docu's official supporters to portray the city as enchanting). We also see Doyle in the set of M. Night Shyamalan's Lady in the Water, glaringly ill-fitted, with the tightly coiled director and his crew patiently tolerating his "eccentricities" and "loose" working style. Doyle, on his part, offers an interesting observation, "In Hollywood, it's 'Give me what I want or I will sue the f*ck out of you."

observation, enthusiastically blurting out "Wow, wow" at anything that strikes his fancy. Doyle himself is such a charming subject, the seemingly focus-less format of the docu works pretty well. Disappointingly, Wong Kar-wai, Fruit Chan, Peter Ho-san Chan and other Hong Kong filmmakers don't give us a whole lot of insight about what they get out of their collaborations with the cinematographer, although the docu accurately captures the absolutely cramped, claustrophobic environment these filmmakers work in (sort of going against the obvious intention behind the docu's official supporters to portray the city as enchanting). We also see Doyle in the set of M. Night Shyamalan's Lady in the Water, glaringly ill-fitted, with the tightly coiled director and his crew patiently tolerating his "eccentricities" and "loose" working style. Doyle, on his part, offers an interesting observation, "In Hollywood, it's 'Give me what I want or I will sue the f*ck out of you."

The Angry Men does a good job of introducing well-known contemporary Korean film directors to the uninitiated. Despite the director's obvious fascination with genre cinema, the docu includes not only usual suspects Ryu, Park, Bong Joon-ho and Kim Jee-woon but also Im Sang-soo (along with a generous clip from The President's Last Bang), Kim Ki-duk and Lee Chang-dong (Hong Sang-soo is the only big shot missing, surprising given his popularity in France). Some viewers might question the explicitly Hong Kong-centered view of Asian cinema permeating it (Tony Rayns, whose comments are by and large well thought-out -- maybe except for his statement that Park Chan-wook's later works constitute an homage to Tarantino's Kill Bill -- is put on the pedestal as the expert on Korean films), and the rather mannered way extreme close-ups of the Korean directors are deployed.

The follow-up discussion began with Kim reminding the audience that the situation has changed, mostly for the worse, for Korean cinema since the docu was filmed. The Korean directors generally concurred. Kim Jee-woon's comparison of his cohorts with the creative force behind the American New Cinema was also a source of debate. (By this comparison director Kim probably did not mean to point to Arthur Penn or Don Siegel) The single most important insight one could learn from the discussion was, despite their cinephilic sensibilities and common love of genre cinema, just how different these directors were from one another. This was made even more evident when a young audience member asked the panel whether any of them would be interested in making a film like Transformers. Ryu Seung-wan flatly stated that he likes neither wu xia novels nor video games and has become even more partial toward the old movies as he gets older. Min Gyu-dong, in an exceedingly gentle and thoughtful manner typical of him, nonetheless clearly indicated that he was bored out of his skull by Transformers. Park Chan-wook claimed that he would rather design something like Metallic Gear Solid 4 than doing a "cutting-edge work" within the confines of a narrative film like Transformers.

The follow-up discussion began with Kim reminding the audience that the situation has changed, mostly for the worse, for Korean cinema since the docu was filmed. The Korean directors generally concurred. Kim Jee-woon's comparison of his cohorts with the creative force behind the American New Cinema was also a source of debate. (By this comparison director Kim probably did not mean to point to Arthur Penn or Don Siegel) The single most important insight one could learn from the discussion was, despite their cinephilic sensibilities and common love of genre cinema, just how different these directors were from one another. This was made even more evident when a young audience member asked the panel whether any of them would be interested in making a film like Transformers. Ryu Seung-wan flatly stated that he likes neither wu xia novels nor video games and has become even more partial toward the old movies as he gets older. Min Gyu-dong, in an exceedingly gentle and thoughtful manner typical of him, nonetheless clearly indicated that he was bored out of his skull by Transformers. Park Chan-wook claimed that he would rather design something like Metallic Gear Solid 4 than doing a "cutting-edge work" within the confines of a narrative film like Transformers.

The interpretation for the panel was done in three languages (English, French and Korean), and, considering the potential for confusion, was expertly managed. The only problem was that the interpreters knew precious little about motion pictures, contemporary or classical, so the participants had to wade through misinterpretations like "A production company known as 'JohnnyTo' is engaged in precisely that type of experiment..."

Adam's Report

My time at PiFan was brief, but well spent. Juggling friends and film, I began with something new for me at a South Korean film festival - music. I met three of my ex-pat-ing friends at Bucheon's Citizen Hall because one of my friends is a huge fan of the Korean band Deercloud and they were playing, along with two other bands, after the international premiere of the Japanese film Nana 2 (dir. Otani Kentaro, pictured). The female lead singer of Deercloud has a nice, husky voice that I've found myself drawn to as well. I anxiously await their CD as my friend has, since they've been delayed in its production having to hone a new drummer after their original drummer was called in for his obligatory military service, complications one would think quite a few young Korean bands run into. Deercloud shared billing with two other woman-fronted bands, including a lite-riot-grrrl band called something like Scary Cat, but I'm not sure if that's correct. One of the gimmicks of that band's lead singer was to occasionally make a piercing scream that caused me to face up to how old I've become, wanting to say after the second scream, 'Please don't'.

My time at PiFan was brief, but well spent. Juggling friends and film, I began with something new for me at a South Korean film festival - music. I met three of my ex-pat-ing friends at Bucheon's Citizen Hall because one of my friends is a huge fan of the Korean band Deercloud and they were playing, along with two other bands, after the international premiere of the Japanese film Nana 2 (dir. Otani Kentaro, pictured). The female lead singer of Deercloud has a nice, husky voice that I've found myself drawn to as well. I anxiously await their CD as my friend has, since they've been delayed in its production having to hone a new drummer after their original drummer was called in for his obligatory military service, complications one would think quite a few young Korean bands run into. Deercloud shared billing with two other woman-fronted bands, including a lite-riot-grrrl band called something like Scary Cat, but I'm not sure if that's correct. One of the gimmicks of that band's lead singer was to occasionally make a piercing scream that caused me to face up to how old I've become, wanting to say after the second scream, 'Please don't'.

The films didn't come for me until the next day. During that day, I was able to meet all but one of the film friends/colleagues I'd hoped of meeting, plus made the acquaintance of some new ones, in the nicely random ways that festival chaos allow - Paolo Bertolin in line at the PiFan chartered bus stop, Tom Giammarco in a park outside the CGV theatre, Darcy on our way to E-Mart to look for the plug adaptor we never found, and Kyu at a chocolate cafe outside the CGV. Traveling to films, processing after films, reconnecting after months of seeing each other, these moments are always too brief, but they are still, nonetheless, greatly appreciated and add as much to festivals as the films themselves.

Speaking of the films, I wanted to focus on South Korean films, but the overlap between my schedule and the festival's only enabled me to catch two recent ones - Resurrection of the Butterfly and Beautiful Sunday. The former is salvaged in my mind for the journey it was more so than the finished product. The idea was to couple a student director with a more experienced director, so student Kim Min-sook was coupled with veteran Lee Jung-gook. The film connects the three primary actors through two stories of love triangles. Director Kim's story works off the historical character of Non-gae from the Chosun Dynasty, a kisaeng known for remaining loyal to the Chosun dynasty by killing the Japanese commander who conquers her village rather than transferring her services as a prostitute/performer to the Japanese. Liberties are taken with this historical character's story that might upset the purists in the audience, but no claim is made that this represents what happened. This is merely speculative history, a 'what if' scenario pondering different trajectories from different outcomes, hence part of the reason for its presence in the line-up for this Fantastic Film Festival. The second story finds a man whose head injury limits his recall into the events that preceded his appearance deep into the mountains, where a mountain ranger finds him. Only a diary leads to clues about who this man is and what he's done. Ironically, it is the student's first half that shows greater promise than the veteran's second half. But when I was informed that veteran Director Lee directed the excruciating The Letter (1997), it made sense that the student would surpass the veteran here.

Speaking of the films, I wanted to focus on South Korean films, but the overlap between my schedule and the festival's only enabled me to catch two recent ones - Resurrection of the Butterfly and Beautiful Sunday. The former is salvaged in my mind for the journey it was more so than the finished product. The idea was to couple a student director with a more experienced director, so student Kim Min-sook was coupled with veteran Lee Jung-gook. The film connects the three primary actors through two stories of love triangles. Director Kim's story works off the historical character of Non-gae from the Chosun Dynasty, a kisaeng known for remaining loyal to the Chosun dynasty by killing the Japanese commander who conquers her village rather than transferring her services as a prostitute/performer to the Japanese. Liberties are taken with this historical character's story that might upset the purists in the audience, but no claim is made that this represents what happened. This is merely speculative history, a 'what if' scenario pondering different trajectories from different outcomes, hence part of the reason for its presence in the line-up for this Fantastic Film Festival. The second story finds a man whose head injury limits his recall into the events that preceded his appearance deep into the mountains, where a mountain ranger finds him. Only a diary leads to clues about who this man is and what he's done. Ironically, it is the student's first half that shows greater promise than the veteran's second half. But when I was informed that veteran Director Lee directed the excruciating The Letter (1997), it made sense that the student would surpass the veteran here.

Jin Kwang-kyo's Beautiful Sunday also works with essentially two stories of past and present, but weaves them in and out of each other. Aware of narrative conventions, you know these stories will turn out to be connected, but how they are connected is nuanced enough that many might find the conclusion unexpected. A police detective has been pushed to taking bribes to cover his wife's medical bills and all this stress has also pushed him into various states of insomnia and alcohol abuse. The other story follows a young man whom we soon discover is a rapist. Where this film excels is in some well directed dialogue (at least considering the English translation) in the rapist's story, along with a horrifying revelation of his identity to his wife later on in his story.

I attempted to catch another South Korean film, Kim Sam-ryeok's Aseurai, but a volunteer guided me into the wrong theatre, where my (falsely) assigned seat constrained me too greatly to leave when I finally realized I was about to see the Japanese film Fuckin' Runaway (pictured) instead. Kyu notes above how he had apprehensions about this film directed by Motohashi Keita and initially I thought I was going to agree with him, having an aversion as of late for films that romanticize mental illness. However, the film slowly grew on me as I traveled alongside our main characters, escapees from a mental health facility, for this road trip through Japan, their psyches, and the intersubjective therapies of their friendship and their eventual courtship. What probably most warmed me to the film were its subtle droppings of dialect and the stereotypes Japanese hold about those who possess said vocal signatures. Such are the kinds of cultural nuances I will not fully apprehend, but would like to know more about and hear about from others who have seen this film.

I attempted to catch another South Korean film, Kim Sam-ryeok's Aseurai, but a volunteer guided me into the wrong theatre, where my (falsely) assigned seat constrained me too greatly to leave when I finally realized I was about to see the Japanese film Fuckin' Runaway (pictured) instead. Kyu notes above how he had apprehensions about this film directed by Motohashi Keita and initially I thought I was going to agree with him, having an aversion as of late for films that romanticize mental illness. However, the film slowly grew on me as I traveled alongside our main characters, escapees from a mental health facility, for this road trip through Japan, their psyches, and the intersubjective therapies of their friendship and their eventual courtship. What probably most warmed me to the film were its subtle droppings of dialect and the stereotypes Japanese hold about those who possess said vocal signatures. Such are the kinds of cultural nuances I will not fully apprehend, but would like to know more about and hear about from others who have seen this film.

The only other non-Korean film I saw was the Australian gross-fest Feed. Part of the nightly "Forbidden Zone" at PiFan, director Brett Leonard takes us into the life of an Interpol internet sex crime detective as he investigates a feeder/gainer relationship. The text at the beginning of the film claims this film is based on real events between consenting adults. I'll leave verification of that statement to others, but Feed informs us that feeder/gainer relationship is an S/M variation where one person (the feeder) feeds someone else (the gainer) with the goal of reaching Herculean poundage in the gainer to the point of immobility and complete dependency on the feeder. Our detective has found himself a feeder whose goal appears to be more than that, feeding his gainers to death. (And this leads him from Sydney to, of all places, the Toledo, Ohio suburb of Sylvania, furthering the stereotype of the girth possessed by those of my home state.) This film allows me to utilize one of the newly anointed words by the Mirriam-Webster dictionary - This is a ginormously sick film. Sickness, of course is part of the point of films like this and the type of films festivals like PiFan celebrate. The film suffers from a poor use of actor Jack Thompson and the occasionally heavy-handed dialogue, even heavy-handed for a film of this genre, but otherwise it entertains within its own genre-determined parameters, making you intentionally disgusted and disturbed.

The highlight of the festival for me was the 4-film retrospective of director Lee Bong-rae (pictured). According to the PiFan program, Lee was born in 1922 and studied in Japan where he worked as a journalist. Coming back to the Korean peninsula after the Korean War, he began work as a critic and scriptwriter. Of the four films screened, I caught three - The Petty Middle Manager (1961), New Wife (1962), and A Salaryman (1962), only missing the one given the poor English title of The Door of the Body (1965). Each one I caught left me truly delighted.

The highlight of the festival for me was the 4-film retrospective of director Lee Bong-rae (pictured). According to the PiFan program, Lee was born in 1922 and studied in Japan where he worked as a journalist. Coming back to the Korean peninsula after the Korean War, he began work as a critic and scriptwriter. Of the four films screened, I caught three - The Petty Middle Manager (1961), New Wife (1962), and A Salaryman (1962), only missing the one given the poor English title of The Door of the Body (1965). Each one I caught left me truly delighted.

Apparently, Lee's best known film is The Petty Middle Manager which follows the troubles of a patriarch as his daughter joins his firm just as his boss demands he open up a dance school in the free room on the floor of his division for his boss's mistress. This said boss will return, as will his treacherous ways, in A Salaryman where our ethical patriarch refuses to enable his boss's embezzling of money from the company and finds himself fired and competing for a position at another company with none other than his eldest daughter. Each of these films works its plot tension around the predicament of the rapid modernization of South Korea and its effects on family roles, particularly changing courtship rituals. The changing views of marriage dominate in New Wife where the matriarch attempts to sabotage a son's marriage to a farm girl in hopes of arranging his marriage to a woman of a higher social standing.

Lee's films are engaging and humorous. (Check out the lobby fight scene in New Wife or the awkward scolding of father in front of daughter by father's boss in The Petty Middle Manager.) Each provides wonderful swatches of the wider shifting social tapestry of modernization that South Korea was experiencing in the 60's. (Interestingly, two of the films have a character make disparaging comments about movie-goers. Ironic when you think of it, since such ridicule implicates everyone watching the particular films.) They are also films that are slightly damaged. The first ten minutes of the surviving print of New Wife contains no visuals, only dialogue. (Since New Wife was originally a radio drama, it makes me curious if the dialogue used was from the radio drama rather than the film.) The reverse happens in the middle of A Salaryman, ten minutes of visuals without audio. The quality of the prints is what led the volunteers to apologize to me and other western patrons profusely, almost to the point of appearing to discourage ones attendance. Thankfully, I didn't heed these apologies. (And so as not to give a false impression, the volunteers do a tremendous job at PiFan, as at all South Korean festivals I've attended. In the example I gave above of being guided into the wrong theatre, it was as much my fault as theirs. I should have checked the signage as we were going in.) Although not appropriate for a Fantastic Film Festival, I was glad to have the opportunity to catch this director about whom I was ignorant. Regardless of the presence of such films being an aberration, I have now gone from ignoramus to acolyte concerning Director Lee Bong-rae and will preach his praises from here on out.

Kyu Hyun: Report #2

The future identity of PiFan, as Puchon International Fantastic Film Festival is affectionately known, was one of the topics floating around in the moist, rain-drenched air among the guests, panelists and journalists. Festival Director Han Sang-joon, himself a former journalist and a well-known cinephile/film critic who recently translated a French-language study of Francois Truffaut into Korean, is known to be oriented toward intellectually challenging and aesthetically sophisticated films, but is well-versed enough in the traditions and future directions of fantastic cinema worldwide to avoid making strange choices like putting Breakfast at Tiffany's in the "Family" section of the festival. It seems pretty obvious to me, though, that Han and quite a few others involved with the PiFan want it to be something more than a holy site for the fans of Asian cult horror films. I wouldn't be too surprised if PiFan eventually loses "Fantastic" in "Fantastic Film Festival" and be reborn as "PiFF"--wait, isn't that already taken by Busan? Oh, Busan is now spelled with "B," per the We-don't-want-to-use-McCune-Reischauer-'cause-Chinese-use-Pinyin alphabetization system.

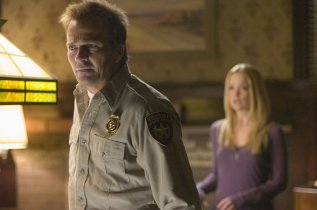

The aforementioned "cult horror film" fans have always had a convenient way of celebrating their tastes, i.e. midnight screenings, but the always-well-attended all-nighters in Puchon, for two years in a row, have been overwhelmed by the Masters of Horror TV series. I mean, yes, MOH have presented really great horror shorts in the rate of maybe one per every four episodes, and in South Korea, where the DVD market is barely showing signs of life, it makes sense that both fans of classic horror (recognizing name-value directors like Tobe Hooper, Joe Dante and Dario Argento) and casual fantasy fans would descend on Puchon to watch the episodes projected on big screens. I managed to catch three episodes (Tobe Hooper's The Damned Thing [pictured], Stuart Gordon's Black Cat and John Landis's Family), all enthusiastically received by the overwhelmingly young Korean audience.

The aforementioned "cult horror film" fans have always had a convenient way of celebrating their tastes, i.e. midnight screenings, but the always-well-attended all-nighters in Puchon, for two years in a row, have been overwhelmed by the Masters of Horror TV series. I mean, yes, MOH have presented really great horror shorts in the rate of maybe one per every four episodes, and in South Korea, where the DVD market is barely showing signs of life, it makes sense that both fans of classic horror (recognizing name-value directors like Tobe Hooper, Joe Dante and Dario Argento) and casual fantasy fans would descend on Puchon to watch the episodes projected on big screens. I managed to catch three episodes (Tobe Hooper's The Damned Thing [pictured], Stuart Gordon's Black Cat and John Landis's Family), all enthusiastically received by the overwhelmingly young Korean audience.

By sheer chance, I also caught Kaw, a direct-to-DVD quality update of Hitchcock's Bird with ravens instead of seagulls, and it was a mighty confusing experience because Sean Patrick Flannery (most famous for playing the arch-villain Greg Stillson in the TV drama Dead Zone) plays a dour and depressed sheriff in that movie and also plays a dour and depressed sheriff in The Damned Thing. What the heck? Anyway, Kaw is simply a generic nature-runs-amok film in which, of all things, Mad Cow Disease is given as an explanation for the raven's strange behavior, including banding together as packs and apparently developing military strategies against hapless humans. It had never occurred to me that Mad Cow Disease actually could make the infected animals smarter before killing them off. The Damned Thing was a trifle better, mostly more energetic, with blood and guts flying off with greater enthusiasm, but even though penned by an ace screenwriter (Richard Christian Matheson), it really didn't do a good job of adapting Ambrose Bierce's short story, which by the way keeps the monster truly invisible until the very end. The episode's version of the monster is disappointingly similar to the oil-slick

beastie in Dean Koontz's Phantom, and its bleak ending was telegraphed well ahead.

John Landis's Family was a notch above the ultimately pointless Damned Thing,

turning out to be a well-scripted if predictable horror comedy, reminiscent of Bob Balaban's underrated Parents. George Wendt is well-cast as the psychotic protagonist and gives a good performance but I think it would have been more fun if Landis had cast someone like Bruce Willis in the role. Nah, maybe not.

John Landis's Family was a notch above the ultimately pointless Damned Thing,

turning out to be a well-scripted if predictable horror comedy, reminiscent of Bob Balaban's underrated Parents. George Wendt is well-cast as the psychotic protagonist and gives a good performance but I think it would have been more fun if Landis had cast someone like Bruce Willis in the role. Nah, maybe not.

In any case, it was Stuart Gordon's Black Cat (pictured) that stole everyone's thunder--or tongue. Jeffrey Combs of Re-Animator fame gives perhaps the performance of his career as Edgar Alan Poe, whose writer's block may or may not be resolved by the presence of an evil black cat Pluto, beloved by his tuberculosis-stricken teenage wife Veronica. The bulk of the episode, other than a few wink-wink homages to Roger Corman's Poe adaptations, is a completely faithful retelling of Poe's classic story. There are no gimmicks, no CGI, no synth noodledy-doodle score: it's simply Poe in his own voice, as the tortured alcoholic genius re-fashions his pathological obsessions and propensity for petty cruelty into a fictional descent into hell that has lost none of its power to grab and squeeze a viewer's heart after more than a century. A loving tribute to Poe, the Black Cat episode drew a spontaneous applause from the young audience and may well be the best film I have seen in the entire festival. So there is good reason why TV is trumping theatrical cinema in the US now, after all.

This year's Korean classics retrospective at Pucheon was an inspired choice, a triptych of comedies and one melodrama directed by Lee Bong-rae. Samdeung gwajang, (The Third-Rate Section Chief, 1961) given an awful English title A Petty Middle Manager, is not only a rare glimpse into the milieu of the post-April 19 "revolution" Korea, after students and citizens had toppled Syngman Rhee's dictatorship in 1960, but also a showcase for the amazing acting prowess of Kim Seung-ho. Kim plays a decent, soft-spoken salaryman patriarch critically lacking in self-confidence, and forced to take responsibility for the improper use of company resources by his villainous superior (Kim Hee-gap). Nearly all of Section Chief's characters are smart, capable of witty repartee, and optimistic to the point that they seem to hail from some alternative history of Korea. At the center is Kim Seung-ho, whose subtle performance, full of pathos yet with twinkles in his eyes, makes even the patriarchal I-am-the-bus-driver sermon he delivers at the end wholly endearing and believable. The film's only glaring problem is that Do Geum-bong, who plays the protagonist's vivacious and ambitious daughter, looks only four or five younger than Hwang Jeong-soon, playing her mother. While not exactly an undiscovered gem, The Third-Rate Section Chief nonetheless confirms my view that there are many more worthwhile '60s Korean films to be discovered.

Awards

FEATURES

Best of Puchon: 13 (Thailand) by Chookiet Sakveerakul.

Best of Puchon: 13 (Thailand) by Chookiet Sakveerakul.

Best Director: Grimm Love (Germany) by Martin Weisz.

Best Actor: Thomas Kretschmann and Thomas Huber, Grimm Love (Germany).

Best Actress: Charlene Choi, Diary (Hong Kong).

Jury's Choice: Special (USA) by Hal Haberman and Jeremy Passmore.

Audience Award: The Matsugane Potshot Affair (Japan) by Yamashita Nobuhiro.

* Jury Members: Chung Chang-hwa (chair) (film director, Korea); Mick Garris (producer/director, USA); Sabrina Baracetti (festival director, Udine Far East Film Festival, Italy); Derek Elley (critic, Variety, UK); Sono Sion (film director, Japan).

SHORTS

Best Short Film: ($5,000) Juanito Under the Orange Tree (Colombia) by Juan Carlos Villamizar.

Jury's Choice, Shorts: ($5,000) Sweat (Korea) by Na Hong-jin.

Audience Award, Shorts: The Eyes of Edward James (Canada) by Rodrigo Gudino.

Best Korean Short: (5 million won) The Villains by Chang Hoon.

* Jury Members: Xei Fei (director, China); Nagai Go (manga artist/director, Japan); Lee Sung-gang (animator/director, Korea).

European Fantastic Film Festival Federation Asian Award: 13 (Thailand) by Chookiet Sakveerakul.