A Conversation With Filmmaker/Festival Director Lee Jang-ho

by Paolo Bertolin

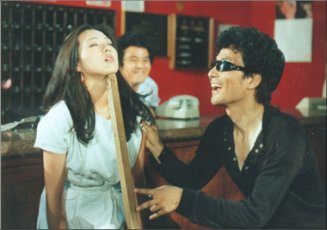

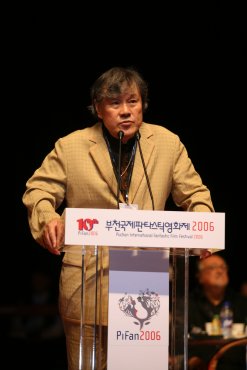

Director Lee Jang-ho (born in 1945) was one of the key personalities in Korean cinema of the seventies and eighties. His best remembered works include the controversial Declaration of Fools ("Babo Seoneon," 1983); Eo-u-dong (1985), one of the most successful Korean films of the eighties; and the widely acclaimed The Man With Three Coffins ("Nageune-neun Gileseodo Swiji-anneunda," 1987). Now inactive as a filmmaker for more than a decade, Lee has nevertheless continued working in the film world, in particular by being one of the initiators of PiFan, i.e. the Puchon International Fantastic Film Festival. Early in 2006 he was appointed as new director of PiFan, and invested with the delicate task of resurrecting the event after the thorny controversy that surrounded the previous edition (which led to a boycott from the Korean film industry and the establishment of a counter-festival symbolically named RealFanta). We talked with Lee during the festival, one day ahead of the closing ceremony.

Under which circumstances were you asked to chair PiFan this year? What specifically did your work consist of in reorganizing the festival, after last year's troubled edition?

Under which circumstances were you asked to chair PiFan this year? What specifically did your work consist of in reorganizing the festival, after last year's troubled edition?

In the very beginning, I was among those who suggested to Bucheon City Council that they start a film festival, and I was the chairman of the very first edition of PiFan. Ever since, it has been a very successful endeavour, and these past ten years I feel like I have played the part of a surgeon who tries to heal the wounds and scars of PiFan, especially regarding what happened last year. As Festival Director of this tenth edition, the first thing I had to do was to regain the trust of the people from the film industry, and recover the reputation of PiFan. It was not easy, and I had to work hard on it. I also have been suggesting innovations in the way the festival is organized, and I had to face opposition to my demands of reforms. In the end, I felt my main job always boiled down to persuading people, either to renew their trust in the festival or to accept reforms in its structure. There is still work to do on both fronts, but I believe that for the eleventh PiFan we will manage to regain the full support of people in the film industry. This year we had to negotiate and regain trust; for the 10th edition there has been no boycott of the festival, but for 2007 I strongly believe the industry will come back to PiFan spontaneously.

Will you still be director of PiFan next year or was it just a one-time experience?

Of course, I will still be Chairman of PiFan next year. Now that a solid foundation is being laid, we need to keep piling up the bricks!

What do you think were the strongest points of this year's edition? Were there, on the other hand, weaker spots that you think will need improvement in the future?

Generally speaking, the main thing I would like to do is to change the image of the fantastic film festival, which up until now seemed to be focused on horror films only. I would like to expand the concept of the fantastic film festival or of fantasy film to a broader meaning, inclusive of various, different types of movies. I would like the festival to always feature special programs, such as this year's on Shin Sang-ok or the Korean Director's Cut. For instance, next year my intention would be to feature a program of musicals from all over the world.

This year, the festival featured a tribute to Shin Sang-ok, by showing six of his pictures belonging to the fantastic genre. Since you had the chance to work with Shin more than once, could you say something about your memories of him and his way of working?

When I was working with Shin Sang-ok I was still very young and was strongly impressed by his charismatic character. It was hard work, but since I was thinking it was a real honour to work with him, I could not even feel the pain and harshness. Even to this day, whenever I have a dream about Shin, I always see myself as working for him as assistant director. I worked with him for eight years, but it was not until the fourth year that he started remembering my name. Prior to that, my name was just "Hey, you!"; after four years, when he finally called me by my name, I nearly cried...

Your own career as a movie director spanned almost three decades, but you have been mostly active in times when Korean films still lacked international recognition. Moreover, those were times when directors had to face the strict control of censorship. Could you tell us something about making films in South Korea during the 70s and 80s?

Your own career as a movie director spanned almost three decades, but you have been mostly active in times when Korean films still lacked international recognition. Moreover, those were times when directors had to face the strict control of censorship. Could you tell us something about making films in South Korea during the 70s and 80s?

It was a really depressing time for Korean cinema. When I made the movie Declaration of Fools, I really had made up my mind to leave the industry after its completion. At the beginning of that film there is a film director committing suicide; to me, such an image meant that the director of the film was not taking any responsibility whatsoever, even for the film itself. Thus, I also wanted the film to be totally 'messy', I wanted it to be a not-well-made film. However, critics loved it, and it was greeted by excellent reviews, even if I intended to make it as a bad movie... Declaration of Fools was meant to be my own cinematic suicide, yet it turned the other way round. When reporters asked me what my intentions were in making such film, though, I used to always answer it wasn't just me who made it, but me together with the military government. If there hadn't been a military government at that time, Declaration of Fools could have not been made in the first place, and it would have not been so replete with energy.

What were the sequences or lines of dialogue in your film included in the Korean Director's Cut program, Children of Darkness ("Eodum-ui Jashikdeul" a.k.a. People of Dark Streets, 1981), that created discontent with the censors? Was that your only film that underwent cuts from censorship?

There was actually a large number: it is difficult even to remember them all. And, of course, many of my films shared the same fate. In particular, for Geurae, Geurae, Oneuleun Annyeong (Yes, Goodbye for Today, 1976) the censorship asked for the integral cut of the entire last seven minutes or so. And they were also in disagreement with the title, which they found too depressive and suicidal!

In the opening credits Children of Darkness is presented as the first in a series of cinematic adaptations of the works of Lee Dong-chul. At the end of the film, if I am not wrong, there is a line suggesting a sort of 'to be continued'. Was there actually a follow-up to Children of Darkness?

In the opening credits Children of Darkness is presented as the first in a series of cinematic adaptations of the works of Lee Dong-chul. At the end of the film, if I am not wrong, there is a line suggesting a sort of 'to be continued'. Was there actually a follow-up to Children of Darkness?

The film is based upon a book, which was itself taken from real life experiences. It was actually a thick tome, and I intended to use it as source for a series of three films. Children of Darkness, hence, was meant as the first in a triptych that I could not complete. The script for the film was based on a story that took up only three pages in the book, and was bound to be followed by two more stories. But the government would not allow me to do so; that is one of the reasons why a few years later I went on to make Declaration of Fools, about the suicide of a director!

Your latest effort as director dates back to 1995. Do you think you might some day return behind the camera to make a new film?

Declaration of Genius ("Cheonjae-seoneun") was released in 1995 and was not really successful. I think that film lacked energy, because there was no longer a real enemy for me to fight against, as in my previous movies. Under the rule of the military government it was easy to identify a target to aim at, but when freedom of expression came in, I felt like I didn't have any real enemy anymore. Thus, I thought of triggering my angst again myself, but I was not convinced, and the outcome lacked energy and was unsuccessful.

In the film Cinderella Man (Ron Howard, 2005) there was a great line that sheds light on my feelings as well. The wife of the protagonist always keeps asking him to stop boxing, while he instead continues fighting all the time. To explain why, he utters a line that more or less says "While I was doing boxing, I always knew who was punching me, who was the enemy for me," and that is also why, during the Great Depression, when he was kept from boxing by the economic crisis, he really could not fathom who his enemy was. I felt exactly the same way when we finally achieved freedom of expression, as all the enemies seemed to disappear. I haven't been able to find any new enemy so far, although I am doing research right now... So, I think I might be able to make a new film, say by 2010, but it is going to take a little time...

What is your feeling towards the swift change that has happened in Korean cinema in the last decade or so? Also, what is your thought about the virtual 'disappearance' of filmmakers from previous generations, whom, apart from Im Kwon-taek, seem to have been forgotten and have a hard time making new films or having them released (which was also the case for Shin Sang-ok and his swan song Winter Story)?

What is your feeling towards the swift change that has happened in Korean cinema in the last decade or so? Also, what is your thought about the virtual 'disappearance' of filmmakers from previous generations, whom, apart from Im Kwon-taek, seem to have been forgotten and have a hard time making new films or having them released (which was also the case for Shin Sang-ok and his swan song Winter Story)?

When Korea became a democratic country, freedom of expression was no longer a dream, but a reality. This change in environment, which meant an improved situation for filmmaking, eventually led to a system that is based only on commercialism and profit, and that is ruled by the dictates of the star system, just like Hollywood. It seems as if, with the change in environment, the mindset that conceived filmmaking as a struggle suddenly disappeared, to be replaced by a new one, striving only to find sensational subjects. Nowadays, it seems like there are not that many people left who are interested in finding and exposing problems in our society. Thus, between the younger and the older generation of Korean directors there is a wide gap: all the experiences and viewpoints on the world from the old generation are not really considered or cared about by the younger generation; they kind of refuse them, as if they don't need them. Now, what everyone is looking for in films is just plain fun: that is why you see more films filled with swearing rather than reality!

In light of what you just argued, is there actually any contemporary director whose work you admire, or who you think is still accounting for the plights of Korean society?

I actually think there are a lot of good directors in contemporary Korean cinema. What has changed is the society, the environment around directors. Back in my days, we were more sensitive towards issues of power in our society and we criticized the elite. Now that the film industry itself has become so commercially oriented, and it has acquired so much power for itself, it is obviously difficult to think and act in the same manner, mainly because directors themselves have now entered the elite. It seems to me that the directors of the younger generation no more rely on the observation of their surrounding social reality, than they care about the commercial impact of their work. At least this is what I think...

Paolo Bertolin, BUCHEON July 2006