Film Awards Ceremonies in Korea

Korea established its first film awards ceremonies in the 1950s, as the film industry began its post-war recovery. The decade saw the establishment of the Seoul Cultural Awards (launched in 1955 by the City of Seoul), the Golden Dragon Awards

(launched in 1955 by a group of filmmakers), the Buil Awards (launched in 1958 by Busan Daily News), the Quality Film Awards (launched in 1959 by the Ministry of Education), the Film Art Awards (launched in 1959 by the critical magazine Film Art), and the Korean Film Awards (launched in 1959 by the Industry and Economic Daily Newspaper). None of

these still exist today. Subsequent decades tell a similar story of many short-lived awards ceremonies which were later

halted due to the bankruptcy or reorganization of their sponsors.

Only a few of Korea's awards ceremonies boast a long history. Korea's longest-running film awards are the Grand Bell ("Daejong") Awards, which were first established in 1962 by the Ministry of Culture and Information. Although it underwent some changes in format in the late 1960s and has missed a few years here and there, popular opinion recognizes the government-sponsored event as the most prestigious -- or at least the best known -- of Korea's awards ceremonies. The Grand Bell's biggest rival is the privately-financed Blue Dragon ("Cheongryong") Awards, which were launched in 1963 by the Chosun Ilbo newspaper but later disbanded in the 1970s. In 1990 the Sports Chosun newspaper revived the awards, and they have been held every year since. The hosting of the Grand Bell Awards in the spring and the Blue Dragon Awards in December tend to draw the most local press coverage.

Only a few of Korea's awards ceremonies boast a long history. Korea's longest-running film awards are the Grand Bell ("Daejong") Awards, which were first established in 1962 by the Ministry of Culture and Information. Although it underwent some changes in format in the late 1960s and has missed a few years here and there, popular opinion recognizes the government-sponsored event as the most prestigious -- or at least the best known -- of Korea's awards ceremonies. The Grand Bell's biggest rival is the privately-financed Blue Dragon ("Cheongryong") Awards, which were launched in 1963 by the Chosun Ilbo newspaper but later disbanded in the 1970s. In 1990 the Sports Chosun newspaper revived the awards, and they have been held every year since. The hosting of the Grand Bell Awards in the spring and the Blue Dragon Awards in December tend to draw the most local press coverage.

A sampling of other awards ceremonies that currently exist include the Baek Sang Art Awards (run since 1965 by the Hankook Ilbo newspaper; covers film, TV, and theater); the Critics Choice Awards ("Yeongpyeong-sang," established in 1980 by the Korean Film Critics Society); the Chunsa Film Art Awards (founded in 1990 by the Korea Film Directors' Society and named after the pioneering Korean filmmaker Na Un-kyu); the Pusan Film Critics Awards (founded in 2000 by the Pusan Film Critics Association); the Directors' Cut Awards (launched in 1998 by director Lee Hyun-seung, based on voting by young directors); and the Golden Cinema Festival ("Hwanggeum-chwalyeong-sang," launched in 1977 by the Korean Society of Cinematographers).

Korean Film Awards, 1962-present

Microsoft Excel file

(Click on the tabs at the bottom of the file to navigate)

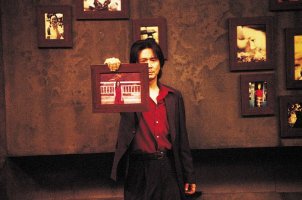

As with Korean filmmaking in general, the various awards ceremonies have become a site of both political and popular contention over the years. Past military governments have taken an active interest in the awards ceremonies' ability to influence popular opinion. For many years the Grand Bell and other major awards ceremonies presented a special "Anti-Communism" prize for the feature that best depicted the evils of communism. Other films with political themes were barred from eligibility, one example being the 1981 film adaptation of the novel A Small Ball Launched by a Dwarf (pictured below left). Although the film was a critical favorite and considered a front-runner for the Best Picture prize, on the day of the awards ceremony it was removed from eligibility due to pressure from the new military government.

In recent years, different kinds of controversy have surfaced, such as accusations of vote-buying and corruption in the late 1990s. The Blue Dragon Awards has also been hindered by its association with corporate parent the Chosun Ilbo, one of Korea's most conservative right-wing newspapers. Several film companies, notably East Film which produced Oasis (2002), have refused nominations to protest against the political stance of the Chosun Ilbo.

In recent years, different kinds of controversy have surfaced, such as accusations of vote-buying and corruption in the late 1990s. The Blue Dragon Awards has also been hindered by its association with corporate parent the Chosun Ilbo, one of Korea's most conservative right-wing newspapers. Several film companies, notably East Film which produced Oasis (2002), have refused nominations to protest against the political stance of the Chosun Ilbo.

From the early 2000s, strong viewer objections to the awards ceremonies' choices have also caused controversy. The Grand Bell Awards in 2001, in which the little-watched A Day won Best Director and Best Actress, drew particularly fierce outrage from viewers, leading to the resignation of the organizing committee and a new nomination system that factors in the opinions of ordinary viewers (for better or for worse).

A public opinion poll held in July 2004 was telling: when asked which local film awards ceremony they most respected, the greatest number of respondents (30%) answered "none." The Baek Sang Art Awards (18.7%), Grand Bell Awards (18.7%), Blue Dragon Awards (14.8%), and Critics Choice Awards (11%) each claimed moderate levels of support.

Personally, I feel that the most important value of film awards ceremonies, aside from their glitter, is in establishing a history of achievement that later generations can back on. In future years, cinema fans will be able to look at the awards choices as a rough guide of how films were judged by contemporary critics and viewers. It can also serve as a useful (if incomplete) list of films to watch in order to get a sense of Korean cinema's past achievements.

Judged by these criteria, Korea's established film awards ceremonies fail the test of usefulness. Throughout their history, government interference and organizational mismanagement have resulted in a list of awardees that owe as much to personal/political connections as to artistic achievement. The Korean public seems to recognize this, and the awards ceremonies -- though followed on TV and covered in the press -- have nowhere near the influence on ordinary viewers that awards in other countries do.

I only follow one awards ceremony with interest: the Pusan Film Critics Awards. Established in 2000, this young awards ceremony is run by a small but independent-minded group of critics based in Busan. Each year they announce their choices shortly before the opening of the Pusan International Film Festival (PIFF), and a ceremony is then held at the festival to present the prizes. Their choices are not swayed by popular opinion, but represent a thoughtful and serious attempt to judge the greatest achievements of each year. In a show of support to Korea's most interesting awards ceremony, the past recipients of the Pusan Film Critics Awards are listed below in their entirety.

The Pusan Film Critics Association Awards

2005 (6th ed.), Rules of Dating |

Best Picture 2005 Rules of Dating (dir. Han Jae-rim) |

2004 (5th ed.), Old Boy |

Best Picture 2004 Old Boy (dir. Park Chan-wook) |

2003 (4th ed.), Save the Green Planet |

Best Picture 2003 Save The Green Planet (dir. Jang Jun-hwan) |

2002 (3rd ed.), Sympathy for Mr. Vengeance |

Best Picture 2002: Sympathy for Mr. Vengeance (dir. Park Chan-wook) |

2001 (2nd ed.), One Fine Spring Day |

Best Picture 2001: One Fine Spring Day (dir. Hur Jin-ho) |

2000 (1st ed.), Virgin Stripped Bare by Her Bachelors |

Best Picture 2000: Virgin Stripped Bare by Her Bachelors (dir. Hong Sang-soo) |

* Thanks to Tom Giammarco, Ryan Law, and Tom Swarthout for compiling the Excel document of past award winners.