An Interview with Whang Cheol-mean

by Paolo Bertolin

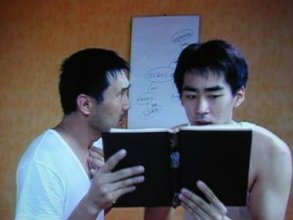

Director Whang Cheol-mean (b. 1960 -- a more conventional transliteration would be 'Hwang Cheol-min') studied Media Studies in Mainz, Germany and Cinematography at the DFFB in Berlin. He has been active in the Korean independent filmmaking sector for more than a decade now, and his prolific output includes The Friend (1991), Fuck Hamlet (1996), My Own Milky Way (2000) and The King and his Sculptor (2004). Whang has also been teaching at the Film Department of Sejong University, and is currently director of the Korean Independent Film Association. His feature film Spying Cam ("Frakchi", 2004), depicting a couple of men who have mysteriously locked themselves up in a sordid motel room, had its international premiere last fall at the Vancouver International Film Festival, and screened in competition at the 34th International Film Festival Rotterdam (Jan 26th-Feb 06th), where it gathered consistent critical praise and won the Fipresci (International Film Critics Federation) Award. This interview session took place in Rotterdam on February 1, 2005.

Note: this interview contains some minor spoilers about the plot of Spying Cam.

What's the meaning of "Frakchi", the original title in Korean?

In a word, you could say it means "spy". In a narrow sense, though, it refers to the context of the military regime Korea experienced in the past. Back then, there were lots of organizations, mainly student-led, that opposed the regime. Frakchi were people sent by the government to infiltrate those organizations in order to collect video materials or information. Usually, they were people blackmailed in some way by the government, whose infiltration was used to incriminate political dissidents and put them in jail.

Where did the idea of the film originally came from?

Actually, I met a guy who had been a frakchi back when I was studying in Germany and that frakchi was a filmmaker himself, just like the character in my film. Ever since I met this real-life person, I thought about making a film on frakchi.

What about the use of Dostojevski's Crime and Punishment in the film?

What about the use of Dostojevski's Crime and Punishment in the film?

The main character has no escape; he has to stay confined in the small space of the motel room. Thanks to Crime and Punishment he finds a way of confessing. The presence of Crime and Punishment also progressively lets the viewer understand and penetrate the point of view of the main character, what he is thinking and what he is feeling.

What about the video camera? In a way, it acts as a crucial catalyst for developments in the interaction between the two protagonists.

First of all, I was very intrigued by the fact that the real-life frakchi who inspired me to make the movie was a filmmaker himself. So, the presence of the video camera was a key asset of the film from the very start. Anyway, the video camera plays a really important role also in conceptual terms. At first, we realize that the frakchi used his camera to spy on people and collect incriminating materials against political opponents, who eventually might have finished up in jail. In the ending segment, though, he turns the camera towards the other side, trying to get compromising information and unwilling confessions from government officials. The camera then reveals itself as a very powerful tool that cuts both ways.

Moreover, the videotaping process he first used to record information meant to frame anti-government protesters, is subsequently subverted in order to redeem him of his guilt. The frakchi uses the camera to record his confessions in order to atone for his sins, and afterwards finds an even better way of sublimating through creativity. Staging and taping Crime and Punishment is for him a process of confessing and redeeming his sins through a creative process.

What about the other character? Throughout the film he seems to develop a psychologically relevant fascination towards the moviemaking process. At first he's reluctant to play the female part of Sonia, but then he really gets into it and, eventually, at the end of the film we see him grabbing the camera and trying to tape his superior. What are the implications of filmmaking on this character who represents authoritarianism and dictatorship?

What about the other character? Throughout the film he seems to develop a psychologically relevant fascination towards the moviemaking process. At first he's reluctant to play the female part of Sonia, but then he really gets into it and, eventually, at the end of the film we see him grabbing the camera and trying to tape his superior. What are the implications of filmmaking on this character who represents authoritarianism and dictatorship?

I believe that the arts bring out kindness in people. At the outset, the relationship between the policeman and the student is somehow characterized by prevarication and hostility, but by rehearsing Crime and Punishment, something changes between them and some kind of spiritual connection starts to bridge them.

The policeman verifies a gradual but great change in his vision. A change that perhaps won't vanish, since we actually don't know what really happens in the finale and what will happen afterwards. It is reported that quite often close relationships grow between political prisoners and their guardians. I believe these spiritual connections between them really have made many people change their mind about their political views and the way of seeing their political adversaries.

The international title, Spying Cam, is much less telling and more ambiguous and is prompt to leave the audience wonder longer about the true nature of the film. If one knows the meaning of "Frakchi" the political background is much more easily identifiable.

In Korea there were people who knew what the word frakchi means before they had seen the movie, and they also felt puzzled and mislead because they were expecting heavy political material. Thus, I think there are both pros and cons in knowing what frakchi means prior to actually seeing the film. On the other hand, it is true that Spying Cam refers only to a part of the film, not revealing its political scope. I guess, however, it is better not to know what frakchi means before of seeing the film; I in fact prefer for you to watch the film without pre-constructed stereotypes or expectations deriving from the reading of the title. It is better not to have any kind of possible preventive meaning, cause that might make it hard to wholly understand the film. It's better to develop your own meaning and explanations step by step, by seeing the film and thinking about it afterwards.

I guess this is the way I like to get to know people, my way of meeting with new people. When I meet someone, I close myself to all kinds of stereotypical images and I take lots of time to get to know the person. So, I would say this is really my style.

What about the circulation of the film? This is a completely independent production made outside the studio system in Korea and you are the director, scriptwriter, editor and d.o.p. of the film. Have you already screened the film in Korea? Is a commercial release envisaged?

What about the circulation of the film? This is a completely independent production made outside the studio system in Korea and you are the director, scriptwriter, editor and d.o.p. of the film. Have you already screened the film in Korea? Is a commercial release envisaged?

At first I did not plan to do it all by myself. On the one hand, though, the budget was very low, and, on the other, I really wanted to make a film with a cogent and unified meaning. Having lots of people working on a film with such a low budget, however, would have meant losing total control over the construction of meaning. That's why I eventually resolved to do it all by myself.

Concerning the circulation of the film, I still haven't found a distributor, but I think that winning a prize here would really help me find one.

What is your aim in regards to your audience, Korean and otherwise? Is the film addressing issues that have a limited political resonance in the recent past of your country, or are you trying to make something that resounds about today as well? Are you also trying to convey some meaning that exceeds the boundaries of South Korea?

This is a film that has many layers of meaning. As you explore and bring out one, then you discover and are faced with a new one. As for Korean audiences, I hope my film would help the people who in the past closed their eyes to the bad happenings and the misery we experienced to grow, and to make them look at the future with new eyes and new points of view. I hope the film could help people grow more mature.

Paolo Bertolin, ROTTERDAM February 2005