2005 Pusan International Film Festival Report

by Darcy Paquet, Adam Hartzell, and Paolo Bertolin

Opening film Three Times, dir Hou Hsiao-hsien

PIFF is in a celebratory mood this year: the upstart festival that has grown to become one of Asia's most recognizable film events is holding its 10th edition. Hoping to make it a special year, organizers have secured almost a million dollars of extra funding for an expanded program (to over 300 films) and for newly-launched events such as the Asian Film Academy (AFA) -- a training program for film students modeled after Berlin's Talent Campus.

Previously written items on Koreanfilm.org that relate to this year's festival include an interview with Mr. Kim Dong-ho by Lalit Rao, some comments about the program after the official press conference, and impressions of Holiday (1968) by Lee Man-hee (which was originally called "A Day Off" in the festival's press materials). The 10th PIFF runs from October 6-14, and we will be providing coverage and updates during and after the event, as time permits.

Quick links:

Darcy Paquet: Opening Ceremony

Adam Hartzell: Laughing at the Past

Darcy Paquet: Big River and Love Talk

Darcy Paquet: PPP Seminar

Paolo Bertolin: The Perfect Winner

Darcy Paquet: Opening ceremony.

PIFF holds its opening ceremonies in front of a mammoth outdoor screen at the Busan Yachting Center, next to the ocean. With a nice view of a long bridge that crosses the nearby harbor, the venue plays host to about 5000 spectators, including a significant number of fans from Japan. Although the itinerary includes short comments from the jury chairman, an introduction from the director of the opening film and such, for most fans the highlight of the ceremony is before it officially starts, when the stars walk in. Parading down a long, red-carpeted raised platform that snakes its way through the middle of the crowd, the VIP guests included actors such as Lee Byung-heon, Ha Ji-won, Kang Dong-won, Kim Hee-sun, Park Joong-hoon, Ryoo Seung-beom and many other recognizable faces. Other Asian countries were represented by Jackie Chan, Vivian Hsu and Tsumabuki Satoshi (the lead from Josee, the Tiger and the Fish, a film that has a considerable cult following in Korea).

There was also a surprise for the audience. Each year the program includes a short musical performance, typically involving a mix of traditional and modern influences, which is met with polite but restrained applause from the crowd. This year, in a twist that was kept secret even from festival staff, pop star BoA appeared on stage to sing two songs. Like actor Bae Yong-joon, BoA is best known in Korea for being hugely popular in Japan -- she was the first Korean singer to top the Japanese charts. In inviting her, organizers were making an unmistakeable nod to so-called "hallyu" or the recent surge in popularity of Korean actors and entertainers in other Asian countries.

There was also a surprise for the audience. Each year the program includes a short musical performance, typically involving a mix of traditional and modern influences, which is met with polite but restrained applause from the crowd. This year, in a twist that was kept secret even from festival staff, pop star BoA appeared on stage to sing two songs. Like actor Bae Yong-joon, BoA is best known in Korea for being hugely popular in Japan -- she was the first Korean singer to top the Japanese charts. In inviting her, organizers were making an unmistakeable nod to so-called "hallyu" or the recent surge in popularity of Korean actors and entertainers in other Asian countries.

All of which points to an interesting dilemma for the festival. PIFF programmers clearly feel more comfortable within the realm of arthouse and small, independent cinema -- this year virtually all of the Korean premieres fit into the "specialist" category. Yet many of the more interesting films coming out of Asia these days have at least one foot planted in the sphere of commercial cinema. Western festivals are finally starting to catch on -- this year large-scale, mainstream Asian commercial features screened at Cannes (A Bittersweet Life and Election) and Venice (Initial D and Seven Swords). Such films almost never screened at major festivals in the past -- John Woo and Tsui Hark were virtually ignored all through the eighties and nineties -- so this represents a new openness, so to speak. PIFF would seem to be perfectly positioned to get in on this game, given the commercial strength of its own industry and its status within the Asian film industry. The question is, does it want to?

Could PIFF do both? Certainly it could screen both micro-budget digital films and huge-scale blockbusters, as it does now. Although the smaller arthouse works dominate this year, there are also films such as Jackie Chan's The Myth in the program. But ultimately any festival has to establish its own identity, including the kind of films that people associate with it, and this is where organizers have to make a choice. If the opening ceremony is any indication of the image the festival wants to project of itself, then it seems PIFF is hedging its bets.

The stars, BoA, and the fireworks seem to represent an attempt to replicate on a smaller scale the glitz that you find at an event like Cannes. Actually, I found it exciting to see PIFF flex its muscles in this regard -- there was not a single Western star at the event (unless you count Jackie Chan), and they were not missed in the slightest. Asia has more than enough youth, dazzle and sex appeal by itself to do without any films or actors from Hollywood.

The stars, BoA, and the fireworks seem to represent an attempt to replicate on a smaller scale the glitz that you find at an event like Cannes. Actually, I found it exciting to see PIFF flex its muscles in this regard -- there was not a single Western star at the event (unless you count Jackie Chan), and they were not missed in the slightest. Asia has more than enough youth, dazzle and sex appeal by itself to do without any films or actors from Hollywood.

The opening night film Three Times by Hou Hsiao-Hsien, in contrast, conjures up an entirely different side of Cannes -- not least because it had already screened there before coming to Pusan. HHH ranks as one of the most recognized Asian auteurs, and anything he makes is considered a virtual shoo-in to the competition section of a top Western festival. Rather than glitz, a film like this represents "prestige" in the festival circuit. But if Pusan wants to get into the prestige game, it's likely to prove self-defeating. No major Asian auteur -- Hou Hsiao-hsien, Jia Zhangke, Wong Kar-wai, Park Chan-wook, etc. -- would pass up a competition slot at Cannes or Venice in order to premiere their film at Pusan. The only real option in this regard is to re-screen a film that has already received wide press attention at another festival, like Three Times (which is a truly great film, but I think this is beside the point) or last year's opener 2046.

Next year I hope PIFF chooses a world premiere as its opening film. One possibility is a big, flashy, star-filled Asian blockbuster to boost the glitz factor. Or else it could choose an accomplished film from a lesser-known Asian director, like The Peter Pan Formula or Chinese film Gimme Kudos from this year's program, which would be utilizing the festival's influence and prestige for a good purpose, rather than having it roll off the back of a film that is already famous. Either choice would be playing to Pusan's strengths, rather than its pride.

Adam Hartzell: Laughing At The Past: A (Very) Limited Audience Study

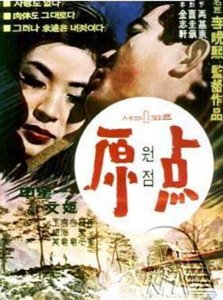

One of the benefits of retrospectives of older works is not so much about history as about now. That is, retrospectives allow us to explore how films from the past are received in the present. And the response of the crowd to certain moments in Lee Man-hee's The Starting Point (1967), one of many films included in a retrospective on director Lee at the 10th Pusan International Film Festival in 2005 (PIFF), provided many opportunities to explore the different tactics that audiences use when receiving an artifact. Particularly in this case, the primarily South Korean audience appeared to receive points of The Starting Point as Camp or with Contempt or Reverence. [Editor's Note: This is a critical essay, so the ending and major plot points will be revealed]

CAMP

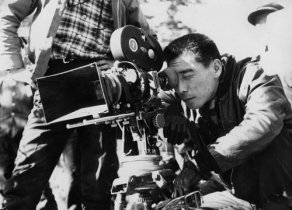

I do not know much about how The Starting Point was received by audiences at the time of its release outside of what cinematographer Suh Jung-min and film critic Cho Young-ju told us following the screening. Apparently the film did well with both audiences and critics, demonstrated by the former buying a lot of tickets and generating positive word of mouth, demonstrated by the latter speaking highly of the film's aesthetics. Lee (pictured right) was obviously earnest and sincere in his directorial intent and I think it's safe to assume it was received that way by audiences of the time. Yet what was earnest and sincere before can seem heavy-handed and over-extended later. Quite a few moments of The Starting Point appeared to be received by this audience as camp, demonstrated in the laughter that erupted at positions in the film that were clearly not intended to be received as humorous.

I do not know much about how The Starting Point was received by audiences at the time of its release outside of what cinematographer Suh Jung-min and film critic Cho Young-ju told us following the screening. Apparently the film did well with both audiences and critics, demonstrated by the former buying a lot of tickets and generating positive word of mouth, demonstrated by the latter speaking highly of the film's aesthetics. Lee (pictured right) was obviously earnest and sincere in his directorial intent and I think it's safe to assume it was received that way by audiences of the time. Yet what was earnest and sincere before can seem heavy-handed and over-extended later. Quite a few moments of The Starting Point appeared to be received by this audience as camp, demonstrated in the laughter that erupted at positions in the film that were clearly not intended to be received as humorous.

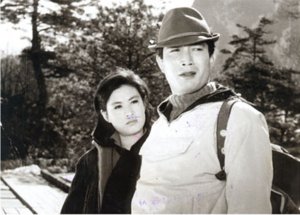

The film opens with a Robber (played by Shin Seong-il) who has been found by whomever it is he's stealing from. In his attempt to escape, The Robber and the robbed proceed to engage in a long - really long - long tussle down flights of stairs. It is not your typical chase scene, it is not your typical fight, in that it takes place mostly on the floor and rather than throwing lots of punches, there is much clutching of legs by the robbed-from. Did I mention this goes on for a real long time? Well, the present day audience began laughing when they felt Lee had over-extended the scene as the robber continued to excruciatingly extend his body along the flight of stairs.

Laughter at the camp in it all returned later when the prostitute (played by Moon Hee) turns her head away abruptly to cry a little melodrama. It returned again during a belt and cane battle on the steps on Mt. Seorak. This is the second of the creative fights on these steps that Lee orchestrates. The first one involves The Robber using his belt as a restraint so as not to fall off when fist-fighting his first foe. This tactic proves successful, for it is his foe that falls to his death as a result. The next fighter brings his cane, however, so The Robber needs a weapon as well. His belt will have to suffice. The laughter reached a pitch at the final moment of this fight when the belt is tightly wound around the handle of the cane. Both The Robber and foe pull on their respective implements in the hopes of getting the other to fall forward. The Robber works with this tension and lets go of his belt, causing his foe to fall to his death. Perhaps nurtured on cartoons that yielded a similar tactic, the crowd found this tricky maneuver hilarious and released a loud uproar when The Robber released his second foe. Yet The Robber's response after this third death he'd caused, (the one during the heist, then the first fight, and now this one), is one of sorrow that he's had to kill three times. This scene was not meant to be seen as humorous, but the camp sensibility of this South Korean audience resisted the seriousness of the past and saw unintentional comedy instead.

CONTEMPT

The most interesting, and the loudest, moment of laughter was addressed at one line of dialogue in the film. When The Prostitute laments that she is a ruined woman, saying something close to 'A ruined woman can become a prostitute; but what becomes of a ruined prostitute?' The Robber seeks to comfort her with the simple line "I'll buy you." The crowd lost it. The Prostitute's overjoyed response, as if this were a wonderful thing to say to a woman, that she is not too lowly beyond purchasing like any other old commodity, only added fuel to the fired up laughter. Obviously, from The Prostitute's response, this line was intended to be received positively. But these South Koreans, knowledgeable of feminisms and new masculinities, less willing to split

themselves and their sisters into Madonnas or Whores, found this line utterly ridiculous. Since the PIFF is well known for its young audience, particularly twenty-something South Koreans and high school kids, this contemptuous reaction to this line speaks of a progressive generation waiting to take charge and move the country closer to its ideal.

The most interesting, and the loudest, moment of laughter was addressed at one line of dialogue in the film. When The Prostitute laments that she is a ruined woman, saying something close to 'A ruined woman can become a prostitute; but what becomes of a ruined prostitute?' The Robber seeks to comfort her with the simple line "I'll buy you." The crowd lost it. The Prostitute's overjoyed response, as if this were a wonderful thing to say to a woman, that she is not too lowly beyond purchasing like any other old commodity, only added fuel to the fired up laughter. Obviously, from The Prostitute's response, this line was intended to be received positively. But these South Koreans, knowledgeable of feminisms and new masculinities, less willing to split

themselves and their sisters into Madonnas or Whores, found this line utterly ridiculous. Since the PIFF is well known for its young audience, particularly twenty-something South Koreans and high school kids, this contemptuous reaction to this line speaks of a progressive generation waiting to take charge and move the country closer to its ideal.

The laughter during the beginning chase scene and ending fight scene can also be seen as contemptuous. In the discussion after the film, Suh and Cho informed the crowd that Lee's intent with the fight scenes at the beginning and ending of the film was to push his artistic style, to be more adventurous, bringing in what would now be seen as an arthouse sensibility. The first roughly fifteen minutes demonstrate this because the two sequences are shown with no dialogue. And the mountainside stair flight fight demonstrates this through the awkward camera angles intended to disorient the audience and impose suspense upon the scene. So the laughter from the audience can also be seen as contempt for Lee's elitist sensibilities, trying too hard to be "artistic" and stylish. The audience very likely may have known what Lee was doing without being told; savvy enough with film techniques to know when a director is trying to be stylish, without needing Suh and Cho to confirm Lee's intent.

REVERENCE

Darcy found something similar at the screening of King Hu's Dragon Inn (1966), people laughing at the martial arts antics and overly-dramatic dialogue. And wasn't this part of what Tsai Ming-Liang was getting at with Goodbye, Dragon Inn (2003)? That people had lost a certain reverence they once had for film, bringing to it camp and contempt, if not indifference, the latter better demonstrating Tsai's take in the speckle of people barely populating the theatre on its night before it officially closes for good? Thankfully, my experience with the twenty-something South Koreans at The Starting Point showed that, in the case of South Korea, Tsai was lamenting a little too soon.

Darcy found something similar at the screening of King Hu's Dragon Inn (1966), people laughing at the martial arts antics and overly-dramatic dialogue. And wasn't this part of what Tsai Ming-Liang was getting at with Goodbye, Dragon Inn (2003)? That people had lost a certain reverence they once had for film, bringing to it camp and contempt, if not indifference, the latter better demonstrating Tsai's take in the speckle of people barely populating the theatre on its night before it officially closes for good? Thankfully, my experience with the twenty-something South Koreans at The Starting Point showed that, in the case of South Korea, Tsai was lamenting a little too soon.

The crowd was not always laughing at Lee. One moment where laughter could have, but didn't erupt, was after the beginning chase scene. For an awkwardly long moment, we watch a stationary shot of a metal gate, the kind you see all over the place here in Busan to close up shops or restaurants. We simply watch this door while a song plays in the background, that's it. We don't cut away to be introduced to the The Prostitute until the song ends. At the question and answer session afterwards, a young woman in the crowd asked about this. But her question was cognizant of multiple possibilities for this strange moment. She wondered if Lee had intended this as a purposeful technique or if this was simply where the credits were supposed to go. The answer is the latter. The print with the credits displayed properly upon the metal gate was too damaged to piece into this print, so they had to go with the other print sans titles and credits. Not only does this show reverence towards Lee as a director, knowing he either had a reason for this or that such didn't truly represent his vision, but it also shows a reverence for the many Korean organizations that have taken on the task of making these old, often severely damaged prints available to modern day audiences. The twenty-something Koreans in the audience know these organizations are working hard and, in this case, gave them the benefit of the doubt.

And then there was the moment of reverence during The Starting Point that truly shows the unique spiritual space that cinema allows us. We watch the screen in the dark, isolated in our chair chambers fenced off from everyone else by our armrests, some of the lucky ones are engaged in arm-locked symbiosis with a lover or friend, but most of us are isolated off with just the happenings on the screen and ourselves. And some of those happenings on the screen truly inspire us with awe. I can remember the moment when my friend, unfamiliar with the works of Charlie Chaplin, saw Modern Times (1936) with me on Christmas Day in the cinematic church that is the Castro Theatre in San Francisco. When Chaplin sent his Tramp character into the gears of the machinery, my friend gasped with such immense awe at what this film, a film from 1936, was showing her. That is when the Church of Cinema is at its most powerful for us atheists, agnostics, and those who find their religious beliefs reinforced or expanded when sitting in the cinema.

Such a moment occurred during the screening of The Starting Point I attended. It began with laughter but it was as if those who did laugh caught themselves and stopped. I expected to hear a mi-an-hae-yo ("I'm sorry") break the silence. When The Robber turns around to walk back up the steps to The Prostitute after causing a second man to fall to his death, we see that a gunman is preparing to shoot him in the back. Light laughter began that demonstrated genre knowledge amongst those in attendance. This laughter was likely in response to the overly tragic tendencies of many South Korean melodramas, particularly from the 1960's. But something happened on the way to this contempt, the laughter stopped mid-laugh, as if something got caught in their throats. Whereas other moments in the film were laughed at in spite of being positioned as serious or hopeful, this moment was permitted its legitimacy by the halting of individual laughs and the overpowering silence that followed, allowing the shot heard in this theatre to echo throughout, to resonate with each individual viewer. This is the reverence that cinema provides that keeps me, and billions of others around the world, coming back. For me it is a weekly ritual like mosque, church, or temple for others. This is what organized religion claimed to provide for me but never followed through on. Cinema, although there are gaps of disappointment, just like my life, occasionally those truly special, reverent moments arise that I can hold onto for sometime, such as how easily I was able to recall the wondrous moments of Invisible Light to Gina Kim when I met her at an industry party here at PIFF, even though I hadn't seen that film in over a year and a half. And the silence of The Starting Point near its ending point underscores this reverence that cinema affords.

Such a moment occurred during the screening of The Starting Point I attended. It began with laughter but it was as if those who did laugh caught themselves and stopped. I expected to hear a mi-an-hae-yo ("I'm sorry") break the silence. When The Robber turns around to walk back up the steps to The Prostitute after causing a second man to fall to his death, we see that a gunman is preparing to shoot him in the back. Light laughter began that demonstrated genre knowledge amongst those in attendance. This laughter was likely in response to the overly tragic tendencies of many South Korean melodramas, particularly from the 1960's. But something happened on the way to this contempt, the laughter stopped mid-laugh, as if something got caught in their throats. Whereas other moments in the film were laughed at in spite of being positioned as serious or hopeful, this moment was permitted its legitimacy by the halting of individual laughs and the overpowering silence that followed, allowing the shot heard in this theatre to echo throughout, to resonate with each individual viewer. This is the reverence that cinema provides that keeps me, and billions of others around the world, coming back. For me it is a weekly ritual like mosque, church, or temple for others. This is what organized religion claimed to provide for me but never followed through on. Cinema, although there are gaps of disappointment, just like my life, occasionally those truly special, reverent moments arise that I can hold onto for sometime, such as how easily I was able to recall the wondrous moments of Invisible Light to Gina Kim when I met her at an industry party here at PIFF, even though I hadn't seen that film in over a year and a half. And the silence of The Starting Point near its ending point underscores this reverence that cinema affords.

POST SCRIPT

The title of this piece is subtitled "A (Very) Limited Audience Study" because I was not able to interview those who laughed to truly hear from them why they laughed. I am speculating and making assumptions about what I heard around me. There may in fact be South Korean cultural differences about which I am unaware that more fully explain the laughter, and deeper twenty-something South Korean cultural differences, and even deeper Busan regional differences, as well. Basically, as so many scholarly journal articles conclude, my hypotheses would need to be further tested before they can become part of a wider accepted theory. But the laughter stayed with me as much as some lovely scenes from The Starting Point, so I hope you will humor me and allow this starting point in audience studies. It's just me geeking out. It's just me testifying to my congregation.

Darcy Paquet: Big River and Love Talk.

It's got to require a certain amount of hutzpah to go and shoot a movie in another culture, particularly when that movie aims to say something about that culture. I've been living in Korea for eight years now, but I'm not sure if I'd have the guts to shoot a film that aims to say something about the Korean experience. There is the seductive idea that one could utilize the critical distance of the outsider to illuminate aspects of a country's culture that its own citizens are unaware of, being too close to see. Although there may be some truth to this, there are also numerous pitfalls that face such efforts, particularly in a medium like film that, for the most part, relies on an illusion of perfect verisimilitude.

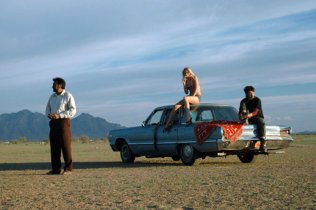

Two works screened by PIFF this year represent attempts by Asian directors to shoot a film in the U.S., and the results in both cases are somewhat mixed. Big River by Japanese director Funahashi Atsushi tells the story of a Japanese man Teppei backpacking his way through Arizona who comes across a man named Ali who has flown in from Pakistan to look for his wife. Eventually the two men hook up with a American woman named Sarah who lives in a trailer park. The film is sort of a road movie, even though all three characters are headed in different directions, and it touches on various issues such as trust among strangers, individuals' sense of freedom, and the post-9/11 atmosphere in the U.S.

Two works screened by PIFF this year represent attempts by Asian directors to shoot a film in the U.S., and the results in both cases are somewhat mixed. Big River by Japanese director Funahashi Atsushi tells the story of a Japanese man Teppei backpacking his way through Arizona who comes across a man named Ali who has flown in from Pakistan to look for his wife. Eventually the two men hook up with a American woman named Sarah who lives in a trailer park. The film is sort of a road movie, even though all three characters are headed in different directions, and it touches on various issues such as trust among strangers, individuals' sense of freedom, and the post-9/11 atmosphere in the U.S.

Love Talk, meanwhile, is Korean director Lee Yoon-ki's followup to This Charming Girl, and it is set within the Korean-American community in Los Angeles -- for Koreans, a culture that shares much with their own, but which in other ways can seem quite distanced. More conventionally structured than This Charming Girl, the film follows several different characters who feel both uncertain and frustrated about the relationships they are involved in, leading them to re-think what they want to do with their lives.

I would argue that both films handle the big themes well enough (even if those themes are nothing new), but are dragged down by the details. Big River is painted in broader strokes, with some humorous and non-humorous set-ups that highlight the cultural differences between the characters, but many of these situations feel more constructed than convincing. Although it might be too harsh to call the characters nothing more than stereotypes, they exist more as abstract concepts than as living, breathing people.

Love Talk has a similar problem with many of the supporting roles, such as the love interests of the three main characters. Convincing details are the key to good characterization, as Lee demonstrated so brilliantly in This Charming Girl, but in Love Talk those small moments that really allow you to see inside a person are quite rare. Clearly it's not an issue of the director's talent, which makes me suspect that the film's problems arise from the difficulty of working in a foreign culture.

Love Talk has a similar problem with many of the supporting roles, such as the love interests of the three main characters. Convincing details are the key to good characterization, as Lee demonstrated so brilliantly in This Charming Girl, but in Love Talk those small moments that really allow you to see inside a person are quite rare. Clearly it's not an issue of the director's talent, which makes me suspect that the film's problems arise from the difficulty of working in a foreign culture.

Both films run up against language problems as well. One of my favorite recent movies is Thai director Pen-ek Ratanaruang's Last Life in the Universe, and I particularly liked the mix of languages in the film. It was convincing because the actors, who were non-native speakers of English, spoke like non-natives. It didn't matter if their grammar was a bit unconventional, because they were never meant to be fluent in the first place. Ratanaruang was also smart enough to keep the dialogue somewhat simple. In these two films however -- especially in Love Talk -- the dialogue appears to have been written by a native speaker, but then put into the mouths of non-native actors, who can't handle the intonation for such complex sentences. The end result is uncomfortable, and immediately pulls you out of the narrative so that you see not two characters speaking to each other, but two actors struggling to deliver their lines. I don't think one should blame the actors for this -- ultimately it's the director who must take responsibility for the dialogue in the film, and how it is executed.

Darcy Paquet: PPP Seminar: "Advanced Window Marketing".

Apart from all the films, parties, press conferences and other events at PIFF, each year there are a certain number of business-related seminars. One of those this year was titled "Advanced Window Marketing", which I suppose could be interpreted in different

ways, but the presenters chose to mainly discuss the issue of ancillary rights (in other

words, formats like DVD, video on demand, cable TV, and new technologies like DMB for mobile phones) and how these relate to overall strategies for releasing Asian films.

words, formats like DVD, video on demand, cable TV, and new technologies like DMB for mobile phones) and how these relate to overall strategies for releasing Asian films.

Four people took part in the seminar: moderator Rob H. Aft, who is an entertainment lawyer based in Hollywood; Jonathan Kim, CEO of the Korean production company Hanmac Films and a co-producer of Silmido; Hamish McAlpine, the head of Tartan Films Distribution, which has operations both in the UK and the US; and Carrie Wong of Hong Kong-based Golden Network Asia, which has handled the distribution of Ong Bak and many other pan-Asian hits.

Rob Aft started discussions by noting that there are a number of factors, such as piracy or the high cost of marketing and releasing films, that are causing some people to rethink the way theatrical and ancillary releases are handled. A few executives, such as new Disney CEO Bob Iger, have wondered aloud whether it might make sense to release films in every format -- in theaters, on DVD, on cable TV, etc -- at the same time. Aft also noted that Korea is a particularly interesting place to study distribution, since in many ways it is the most advanced country in the world in terms of new technologies (such as DMB for mobile phones) and distribution trends.

Next, Jonathan Kim spoke about Korea's problems with ancillary rights. Although the theatrical market in Korea is extremely strong, ancillary markets such as DVD or pay TV are very weak. Roughly 75% of the money earned by Korean film companies comes from the theatrical release, compared to 25% for ancillary and international sales, which is extremely lopsided by international standards. [As a side note, Kim noted how the genre of sex films was dying out in Korea due to the weakness of video/DVD. In the mid-1990s when video was stronger there were many such releases, but because people prefer to watch such films at home, these days it isn't economical to make mainstream sex films]

The usual release pattern in Korea is: (1)Theatrical. (2) Digital theaters (so-called "DVD rooms") where viewers get a small private room; the films are licenced and screened in digital format off a server on a per-view basis. This usually starts one week after the end of the theatrical run. Kim noted that these have come to replace second-run theaters (venues that screen older films for a reduced price), which don't exist in Korea. (3) Video/DVD. The gap between the theatrical run and video releases have always been very short (about three months), due to the influence of chaebol such as Samsung or Daewoo in the 1990s who wanted to support the video market -- due to the fact that both companies were manufacturers of VCRs. These days, the threat of lost revenues due to piracy is keeping this window short. (4) Cable TV, about 6 months after the theatrical run. Kim noted that if cable companies pay enough, it can even come before the video and DVD releases. (5) Free TV, usually another 6 months after cable.

The usual release pattern in Korea is: (1)Theatrical. (2) Digital theaters (so-called "DVD rooms") where viewers get a small private room; the films are licenced and screened in digital format off a server on a per-view basis. This usually starts one week after the end of the theatrical run. Kim noted that these have come to replace second-run theaters (venues that screen older films for a reduced price), which don't exist in Korea. (3) Video/DVD. The gap between the theatrical run and video releases have always been very short (about three months), due to the influence of chaebol such as Samsung or Daewoo in the 1990s who wanted to support the video market -- due to the fact that both companies were manufacturers of VCRs. These days, the threat of lost revenues due to piracy is keeping this window short. (4) Cable TV, about 6 months after the theatrical run. Kim noted that if cable companies pay enough, it can even come before the video and DVD releases. (5) Free TV, usually another 6 months after cable.

Kim then spoke about the problem of illegal downloads in Korea, which he described as "the worst in the world." High quality illegal downloads become available on the internet as soon as a DVD is released. He estimated that the Korean film industry loses $120 million a year due to downloads. Kim also noted that illegal exhibition of films in public places also occurs -- he's even heard of cases where schoolteachers illegally download movies and then screen them for their students.

Stopping this problem is difficult because of the way the law is written and enforced. According to Korean law, unless the rights holders themselves discover who posted the illegal downloads on the internet, it is not illegal. The police will not search for perpetrators. Kim hired a lawyer and managed to find 1000 kids who had engaged in illegal downloading, but then he found that the police refused to book them, saying it was too much work.

The illegal downloading, and in some cases competition from cable TV, are believed to have severely crippled the DVD market. He noted that some companies are starting to give up DVD releases altogether, because they make such little money from it, and the DVD release provides an excellent quality source for pirates. Kim's recommendations include establishing a legal market for downloading movies off the internet, which could be huge since people are accustomed to watching movies on their computers anyway. There also needs to be an effort to establish a "collectible" mindset for DVD, and to convince people that downloads are stealing.

Next, Hamish McAlpine discussed some of the challenges with releasing Asian films in the UK and US markets. He noted that he's been distributing films of all kinds in the UK for 21 years, but in the US only for two. In the UK, Tartan releases 35 films/year theatrically and 80 on video, while in the US it is 12/year theatrically and 40 on video. He noted that theatrical releases in the UK usually last for 6-8 weeks, but as an independent in the US they can't afford to release in all states at the same time. Therefore they start with the big cities and move out to smaller cities later, and the entire release takes 2-3 months. The video/DVD release comes 5-6 months later, and 2-3 months after that is pay TV and cable.

McAlpine argued that word of mouth is still an important factor in releasing a film, so he doesn't believe in releasing simultaneously in theaters and on DVD. There needs to be a gap to maximize video sales or television audiences. Although foreign language films are less predictable, in general if a film grosses $1 million in theaters, it will gross another $1m on video and $500,000 on TV. The big difference is that the theatrical revenues have to be shared, so it results in only $200,000 - $300,000 in profits, while for video and TV you can keep "practically the whole lot." He says DVD is "absolutely the profit driver" in terms of releasing films in the US and UK.

McAlpine argued that word of mouth is still an important factor in releasing a film, so he doesn't believe in releasing simultaneously in theaters and on DVD. There needs to be a gap to maximize video sales or television audiences. Although foreign language films are less predictable, in general if a film grosses $1 million in theaters, it will gross another $1m on video and $500,000 on TV. The big difference is that the theatrical revenues have to be shared, so it results in only $200,000 - $300,000 in profits, while for video and TV you can keep "practically the whole lot." He says DVD is "absolutely the profit driver" in terms of releasing films in the US and UK.

However the fact that DVDs are easily transportable across borders causes problems -- McAlpine referred to this as "the ogre or nemesis that we face." One issue is outright piracy, such as Jonathan Kim discussed, and DVD complicates this by providing such a fabulous master for new pirated versions. The second matter, however, is so-called "grey marketing" where a company owns the rights to one territory, but sells into another territory.

He noted that in the UK this isn't a big problem, since there aren't substantial Asian communities. People get friends to send them DVDs from overseas, and sometimes family shops will sell DVDs from another region, but he said he has no problem with that. (He declined to discuss the internet, saying he "doesn't use computers") The UK is also much stricter about not allowing people to sell films in the UK unless you own the rights to those films.

The US is more difficult, however, because it's easier to set up distribution channels for Asian movies, especially in self-contained ethnic communities. He said there's little one can do about it, other than to release at the same time as a film or DVD is released in its home country. He's been discussing the idea of simultaneous releases with some companies, but for example with the film Old Boy he wanted to take the film to Sundance first, so he had to delay the release.

The greatest challenge comes from companies, mainly coming out of Hong Kong, who buy Korean films and sell them to the US, putting them on sale as if they were a local release. He noted that "when I go to sell my film in the US, I look and it's already in Borders and on Netflicks." This money goes into other people's pockets, which prevents him from releasing more films. He said he regards this as a bigger threat than piracy or online piracy. As such, as soon as Tartan buys a film, they send out a letter to 500 stores and other venders in the US saying that (1) we own this film, and (2) we will sue you if you sell unauthorized copies.

McAlpine also argued that there are three things that Asian producers should insist become part of every sales contract: (1) Buyers should not allow any subtitles to be put on a disc except for the language of the country where it is being released. (2) Video/DVD releases should only be made in the format (PAL or NTSC) that is standard for their home country. (3) Regional coding of DVDs should be strictly enforced.

Finally, Carrie Wong discussed the situation in Hong Kong, which is very much affected by the sitation in mainland China. The biggest challenge for this territory is piracy, which is especially strong in China, and the fact that the window between the theatrical and the video/DVD release in China is only two weeks.

Finally, Carrie Wong discussed the situation in Hong Kong, which is very much affected by the sitation in mainland China. The biggest challenge for this territory is piracy, which is especially strong in China, and the fact that the window between the theatrical and the video/DVD release in China is only two weeks.

At one time the window between theatrical and video was as long as one year, but the threat of piracy has changed all of this. Hong Kong distributors have even tried simultaneous releases of theatrical and DVD, but theaters were angry at the development and a big dispute resulted.

Typically there are marketing costs of US$300,000 to release a film in Hong Kong, and if there is a long gap between the theatrical and video release then they need to advertise again. In most cases though, video companies don't wait a full month for the DVD release. Pay TV follows 6 months after theatrical, and free TV a year after that.

In the case of Ong Bak, the film had been released in Thailand in January 2003, but it didn't come out in Hong Kong until summer 2004. Because they wanted to wait for a summer release, they had to negotiate with Thai companies over the timing of their DVD release. They also strongly pushed for no English subtitles to be put on the Ong Bak DVD releases -- this has become sort of a general policy for them. In the case of The Promise, they negotiated with video companies to delay the release of the DVD, and as compensation they didn't charge as much for DVD rights.

Currently, like in Korea, some companies are planning to offer movie downloads for mobile phones, and so right now there is much discussion about where the window should be for this kind of release.

In general, the panelists expressed strong, passionate opinions about these various issues, but also noted that the commercial situation for Asian films in general has improved. Although the overall quality of Asian films may not have necessarily improved (McAlpine even suggested that Korean films in the mid to low-range are going through somewhat of a crisis), worldwide interest in and openness to Asian cinema is on a steady incline.

Paolo Bertolin: The Perfect Winner: Personal ruminations on Grain in Ear's win in Pusan.

In Pusan almost everybody rejoiced for the win of Zhang Lu's Grain in Ear ("Mang Zhong"). Certainly Zhang himself did, as the US$30,000 attached to the New Currents Award Grain in Ear nabbed will make it easier for him to bring to completion his PPP-presented project Dooman River. But Grain in Ear felt to many as the perfect winner at PIFF.

As PIFF hails itself as a full-fledged celebration of Asian cinemas, it seemed appropriate that a Chinese film won in the centennial of Chinese cinema. This, incidentally, added a further laurel to a year that has already been bountiful for Chinese films and directors at international festivals. Since Grain in Ear is a Korea-backed production striking a chord with Korean audiences for its subject matter (the hardships of a woman from the Korean minority living in China) its triumph also aptly suited the Korean-pride boosting decennial of Asia's leading film festival.

However, I strongly doubt that this was a "perfect winner" for the returns of PIFF itself. I would like to make myself understood, first. I am not questioning here the verdict in terms of artistic choices operated by the jury, i.e. I won't argue whether Grain in Ear was or not the best film in the New Currents competition, as ostensibly many people thought. I instead want to just consider what this win brings to PIFF in terms of image and prestige in the broader frame of the festival circuit and international awareness among press, professionals and cinephiles.

However, I strongly doubt that this was a "perfect winner" for the returns of PIFF itself. I would like to make myself understood, first. I am not questioning here the verdict in terms of artistic choices operated by the jury, i.e. I won't argue whether Grain in Ear was or not the best film in the New Currents competition, as ostensibly many people thought. I instead want to just consider what this win brings to PIFF in terms of image and prestige in the broader frame of the festival circuit and international awareness among press, professionals and cinephiles.

The crucial issue at stake could be summarized just by the reminder that Grain in Ear was not a discovery of Pusan. I myself had previously crossed paths with Zhang's film twice in previous festivals, and published an interview with Zhang in The Korea Times in early July. Since the announcement of the official selection, Grain in Ear appeared as a clear frontrunner among the eleven competitors for the New Currents award, exactly because of its earlier festival exposure.

The film had in fact premiered in May at Cannes' Semaine de la Critique, receiving critical acclaim and some minor awards, then in June it went on to grab the main prize of the Pesaro Film Festival (Italy). This reminder, anyhow, is not meant to argue that the expectations elicited by Grain in Ear, and its competitive advantage over the other New Currents were "unfair". Unequal lineups are actually pretty frequent at festivals, and almost inevitable when not all competitors are world or international premieres.

My point, instead, is that the inscription of Grain in Ear in the highest rank of the 2005 PIFF palmares feels like a frustration of PIFF's proclaimed ambitions. If the festival aims at surging to global recognition comparable to that of Cannes, Venice or Berlin, the win of a film that had such extended prior festival exposure is a major step backward. And more so in the grandeur-laden tenth anniversary of the event!

To external observers, either journalists or professionals, the New Currents Award to Grain in Ear disseminates in fact the image of a "minor league" festival. The kind of festival where, rather than making first-hand discoveries, films already revealed by major events in parallel sections find their (legitimate) consecration.

To give an example resounding to Korean ears, this was a position Locarno Film Festival occupied when Why Has Bodhi Dharma Left for the East? (pictured right) won the Golden Leopard in 1989, scoring an epochal win for a South Korean film in a Western festival. Although the win in Locarno fostered the success of Bae Yong-kyun's film in the international art house circuit (it was the first Korean film to receive theatrical distribution in most Western territories), Bodhi Dharma had already been "discovered" a few months earlier at Cannes' Un Certain Regard. Then, in 1992, new festival director Marco Mueller (currently heading Venice Film Festival) chose to restyle Locarno with a competition of premieres only. The strenuous efforts of Mueller, though initially criticized, brought fruit, and many now label Locarno either as the fourth of the bigger or the first of the smaller festivals.

To give an example resounding to Korean ears, this was a position Locarno Film Festival occupied when Why Has Bodhi Dharma Left for the East? (pictured right) won the Golden Leopard in 1989, scoring an epochal win for a South Korean film in a Western festival. Although the win in Locarno fostered the success of Bae Yong-kyun's film in the international art house circuit (it was the first Korean film to receive theatrical distribution in most Western territories), Bodhi Dharma had already been "discovered" a few months earlier at Cannes' Un Certain Regard. Then, in 1992, new festival director Marco Mueller (currently heading Venice Film Festival) chose to restyle Locarno with a competition of premieres only. The strenuous efforts of Mueller, though initially criticized, brought fruit, and many now label Locarno either as the fourth of the bigger or the first of the smaller festivals.

Hence, what I am advocating here is for Pusan to follow the path of Locarno, and invite premieres only in the New Currents competition from now on. Grain in Ear had been a PPP project, and it undoubtedly had warm support from the festival committee. Its selection for competition, nevertheless, was dubious in the first place (why not take also Li Yu's Dam Street that just screened in Venice, then?), and its eventual win was especially inauspicious, since, as Darcy adequately remarked in one of the above comments, for the second year in a row the grand opening of PIFF boasted the premiere of the "definitive version of the latest masterpiece of an Asian grand master". Unfortunately, both "masterpieces" (2046 and Three Times) had priorly screened in Cannes' competition, and the "definitive version" only added cosmetic, minor interventions. These converging elements all conjure up an undesired gloss of a second-run event for PIFF...

Of course, I am not putting into question PIFF's prominence as leading event in Asia and the festival's laudable commitment towards the support and promotion of Asian cinemas. This primacy is testified by the Pusan Promotion Plan (PPP, the market for quality Asian productions seeking international funding), by the inestimable retrospectives, by the series of academic conferences, by the inception of the Asian Film Academy, by the organizational efficiency and by the staff's dedication to continuous improvement.

Yet, as elsewhere (this year's Berlin Film Festival provides the prime example, with a verdict that was dubbed as "catastrophic"), what remains at the forefront of festival chronicles are laurels. And undoubtedly, Grain in Ear will not earn Pusan Film Festival the visibility and publicity brought by genuine discoveries such as Jealousy is My Middle Name or This Charming Girl. Park Chan-ok's and Lee Yoon-ki's provide good examples of films that fueled their prosperous festival careers with PIFF's New Currents Award, gaining exposure and awards in the West through the Rotterdam or Berlin Film Festivals.

A similar pattern might actually await PIFF 2005's (only) other big winner, Yoon Jong-bin's The Unforgiven (left), which by sweeping four awards appeared as the festival's major revelation. Nevertheless, The Unforgiven's monopoly on secondary awards and the consequent claim of sole festival discovery just worsens things, in that it confirms an external impression that Pusan is the place to discover new Korean talents. Korean, not Asian... Think once again of Park and Lee, add Song Il-gon (whose Flower Island had actually premiered in Venice) and Park Ki-yong or the many films that did not win but were sped on the international festivals route. As a matter of fact, Pusan also served as launching platform to outstanding non-Korean films such as Sanctuary by Chinese-Malay Ho Yuhang or The Missing by Taiwanese Lee Kang-sheng, yet these are outnumbered by Korean ones. This relative lack of non-Korean discoveries strongly questions whether the New Currents competition has really acquired the status of desirable showcase for first and second films in Asia.

A similar pattern might actually await PIFF 2005's (only) other big winner, Yoon Jong-bin's The Unforgiven (left), which by sweeping four awards appeared as the festival's major revelation. Nevertheless, The Unforgiven's monopoly on secondary awards and the consequent claim of sole festival discovery just worsens things, in that it confirms an external impression that Pusan is the place to discover new Korean talents. Korean, not Asian... Think once again of Park and Lee, add Song Il-gon (whose Flower Island had actually premiered in Venice) and Park Ki-yong or the many films that did not win but were sped on the international festivals route. As a matter of fact, Pusan also served as launching platform to outstanding non-Korean films such as Sanctuary by Chinese-Malay Ho Yuhang or The Missing by Taiwanese Lee Kang-sheng, yet these are outnumbered by Korean ones. This relative lack of non-Korean discoveries strongly questions whether the New Currents competition has really acquired the status of desirable showcase for first and second films in Asia.

Without further beating around the bush, the obvious conclusion to my argument is that the New Currents competition arguably remains the Achilles' heel of PIFF. In a festival, the competition is always the focus of attention and its most visible asset, therefore, the directive and selection committee of PIFF should concentrate their future efforts on strengthening the New Currents.

As previously stated, working towards a selection of premieres only is the most advisable first step. Competition for Pusan is and will be undeniably tough, as the festival comes right after the August-September period of an interrupted string of events vying for premieres (Locarno, Montreal, Venice, Toronto, San Sebastian, not to mention the direct competitor Vancouver, whose Dragons and Tigers competition caters debut and sophomore films from Asia as the New Currents). The augmented monetary reward could play as an enticing and persuasive lure to young filmmakers, but this will need verification.

Yet, Pusan might rely upon a real ace in the hole by the means of PPP: some kind of "first view" right might be envisaged when it comes to first and second films, although this might prove unpopular; no doubt the number of first and second films selected should increase (this year's PPP lineup and prizes were encouraging steps in such direction). PPP is unquestionably the key asset that established PIFF as the leading film festival in Asia; in the years coming it could pave the way to wider, global recognition.

Awards and Final Statistics

Programming: 307 films from 73 countries

Total Audience: 192,970 tickets (65% seating rate)

Guests: 6,088 accredited guests (domestic + intl, not including press and PPP)

Press: 1,559 accredited press members (domestic + intl)

PPP Guests: Approx. 1,100 from 320 affiliations in 30 countries (domestic + intl)

Hand Printing: Suzuki Seijun, the late Lee Man-hee

Festival Publications: "Re-mapping of Asian Auteur Cinema 1", "Lee Man-hee, the Poet of the Night", "PIFF's Asian Pantheon".

New Currents Award: Grain in Ear (China/Korea) by Zhang Lu. "The film shows the director's consistent strength, uncompromising story and superb acting." First Special Mention to Silent Holy Stone (China) by Wanma Caidan. Second Special Mention to The Unforgiven by Yoon Jong-bin.

* Jury Members: Abbas Kiarostami (chair) (film director, Iran), Christian Jeune (Cannes Film Festival head of film, France), Mika Kaurismaki (film director and produer, Finland), Lee Hye-young (actor, Korea), Eric Khoo (film director and producer, Singapore).

FIPRESCI Award for best new Asian film from New Currents section: The Unforgiven (Korea) by Yoon Jong-bin. "Yoon's independent film offers a fresh insight into the Korean national character with its harrowing depiction of the psychological violence done to young Korean men during their obligatory military service. Shot in an intimate, naturalistic style, [the film] suggests that the pent-up violence that explodes in such highly stylized popular entertainments as A Bittersweet Life and Oldboy may have its roots in the brutality inflicted by military discipline and an authoritarian social structure -- elements which may have passed from Korean society as a whole but which linger on in the life of the barracks."

NETPAC Award for best Korean film: The Unforgiven (Korea) by Yoon Jong-bin. "[For] its critical reflection on 'masculinity', not only in Korea or the military, but in contemporary society in general."

Sunje Fund Award (20m won) for best Korean short film (tie): Tea & Poison by Joung Yong-ju. "As a contemporary interpretation of Korea's respective ancient folk myth called 'Choyong Song,' the film finds its brilliant path to reflecting the life of our time within an interesting time structure. Director Joung's communication methodology in this film is also noteworthy." / A Bowl of Tea by Kim Young-nam. "While collecting the litte pieces of life in a slow step with flow, the film leaves a lingering satisfaction just like a bowl of warm tea. It is also highlighted by a refined gaze as if quietly following the life without much bearings."

Woonpa Fund Award (20m won) for best Korean documentary (tie): Coreen 2495 by Ha Joon-so / Annyoung Sayonara by Kim Tae-il and Kumiko Kato.

PSB Audience Award for most popular feature in New Currents section: The Unforgiven (Korea) by Yoon Jong-bin.

Korean Cinema Award to individuals who promote Korean cinema abroad: Dieter Kosslick (festival director, Berlin International Film Festival) and Thierry Fremaux (festival director, Cannes Film Festival).

Asian Filmmaker of the Year Award: NHK (broadcaster, Japan).