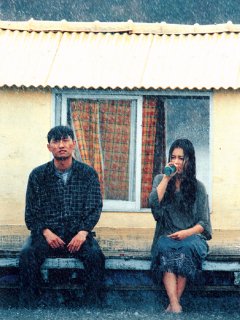

Hee-Jin (played by Suh Jung), Hyun Shik (played by Kim Yoo- suk).

Larisa & Leonid Alekseychuk

IT HURTS

Analytical screening

(extended edition)

Translated by Leonid Alekseychuk

(first published in KINO-KOLO, Ukrainian Film Quarterly, summer 2001)

Strong, vibrant, resilient: the fish dancing on a hook is a feast for the eyes.

A stocky fiftyish angler pulls her out and throws her on his pontoon raft with a doll-house of a cabin. A pretty hooker beside him laughs watching the catch. Her client suggests an appetizer for the forthcoming sex: a slice of "sushi".

A morsel of flesh throbbing with life? Who would refuse such a treat?

Well-being incarnate, the client cuts off the fish's plump sides and lets the rest go.

Free to gambol mutilated in her element.

If you've never heard bare flesh chafe against water, this emphatically understated, matter-of-fact shot will sensitise your ear. If you've never seen a weeping fish, try this time: imperceptible tear beads will remain in water long after she makes a few uncertain, almost incredulous movements and disappears in the deep.

These impulsive sensations are precisely calculated: what is actually shot and recorded compels you to feel what the author feels; a razor-sharp picture carves in you something invisible and indelible; the image and your reaction to it are inseparable parts of the scene, one without the other would render it painfully unfinished.

Well, this is what excellent directing is all about.

That stripped fish alone is a passionate plea in defence of skinned people. Both watchers and participants, we avidly absorb this universal agony, impersonated by a living creature and personalized in a human being.

Well, this is what we call poetry. It heals by hurting, the deeper the wound the sharper the pleasure to feel it.

Despite being taught a hard lesson, the stripped fish will bite again.

From the hands of another angler, she'll get away with much less trouble.

That tall and handsome fellow could not care less about fishing. On the run from the police, he hangs on the hook himself. A floating hut on the lake, one of many in this fishing camp site, is the fugitive's hideout. He just feigns angling, often on an empty hook.

In a fit of despair, while chopping at the catch furiously and endlessly, until that throbbing sushi turns into a bloody mash, in the mutilated fish he recognizes his sworn sister, in her bloody wounds his own, and lets her go. She is his next of kin. Actually theirs: the camp's owner and manager - as well as his lover - is another creature with bleeding flanks.

* * *

These are just two scenes from a film, born initially from word and into word recondensed. Not back into word, but forward, into a new text attempting to preserve the intensity of acting and scenery through personal perception.

In other words, an emotional summary: a heresy for the critic. Supposed to be cold as a dog's nose, that unfortunate creature is banned from using any artistic means while discussing art. Shouldn't the excellence of a judge be judged by his detachment from emotions raging in the courtroom?

Depends. Passion for truth is not only a strong emotion, but also the only way to examine the case in all its fullness and complexity. Only passion, not indifference, enables the judge to side with both sides and rise above both. This is tenfold true when applied to art.

On hearing of an unfamiliar artistic phenomenon, what do we prefer: a dry professional approval and/or frustration, an academic lecture or a trustworthy person's spontaneous outburst? Be it admiration or disappointment, the viewer often justifies either attitude by describing its source. Thus stimulated to see the work, you might react to it differently, but it does not mean that you and your friend have seen different films: surprisingly, one's pronounced attitude does not distort the source but makes it multidimensional.

On hearing of an unfamiliar artistic phenomenon, what do we prefer: a dry professional approval and/or frustration, an academic lecture or a trustworthy person's spontaneous outburst? Be it admiration or disappointment, the viewer often justifies either attitude by describing its source. Thus stimulated to see the work, you might react to it differently, but it does not mean that you and your friend have seen different films: surprisingly, one's pronounced attitude does not distort the source but makes it multidimensional.

To retell as clearly, as vividly and as fully as possible any film (in our case, The Isle by Korean director Kim Ki Duk) we have, in a certain sense, to appropriate it (as any viewer does instinctively) and take all the responsibilities implied (as remarkably few critics do intentionally). Instead of shooting around incontestable opinions on a haphazardly encapsulated work, we'll try to match the filmmaker's hellish investment at least with an attentive look at it - together with the readers, of course, no matter whether they saw the film or not.

Those who didn't might get hooked on the story; those who did might realize that they have seen precious little or nothing at all: the gain is clear in both cases.

Nor should the traps be ignored. What is more risky: to smear somebody else's canvas with an intrusive brush or to dim the original colours with a monochrome abstract?

Since any retelling, impersonal or too personal, is always an interpretation, the original's refraction through the teller's crystalline lens, where is the midpoint between a raving admirer and a lifeless dummy?

Quite a trade: without a literary critic's freedom to quote the original!

What should the critic project on the page: colours or colourlessness, creative writing or a chilling verdict?

Should we analyse a dry extract or stain the page with real blood? In the latter case, wouldn't such haemorrhage, commonly a filmmaker's lot, unsettle the critic's Olympian detachment?

When prey to such tragic doubts, testing both extremes seems a reasonable solution.

Sincere interest implies a delicate touch: even a telegram reveals whether it was dictated by love or indifference.

Anything you like except gawking with a fish eye at a weeping fish.

Pity her performer's name is not mentioned in the titles. Being the third protagonist after the leading couple -- and moreover -- an integral third of that strange trinity, she merits such an honour.

Although the human protagonists don't really need names either. Lest only to distinguish themselves from other fish.

Who are they, those two on the lake?

* * *

Here is a brief synopsis from a festival program:

"Hee Jin lives, selling the fishermen meals during the day and her body at night. On the lake arrives ex- policeman Hyun Shik, who has killed his unfaithful girlfriend. He tries to commit suicide, but Hee Jin prevents it, and then seduces Hyun Shik. Sex with Hee Jin becomes for him a narcotic against a physical and mental pain. Attracted to sex like fish to one hook, both arrive at an unexpected catastrophe."

Concise and clear. Wonderful for an anatomic museum.

Let it be however: without a skeleton, flesh will grow neither.

Here, at least, one can see the hands of the director and his press agents, constrained to pour a lake into a glass. They've even managed to preserve a droplet of poetry and to cast a hook with a narco-bait. (Just as compressed, many a newspaper critics' summaries are often diluted by emptiness. Barely recapturing the storyline, their detached authors believe naively to express the work's very essence.)

How about the choice of heroes? Are they worthy of watching? A policeman and a prostitute: doesn't the screen swarm of their clones like a spawning-ground of hard roe?

How about the choice of heroes? Are they worthy of watching? A policeman and a prostitute: doesn't the screen swarm of their clones like a spawning-ground of hard roe?

As far as Hyun Shik is concerned, neither his profession nor his crime are of any dramatic relevance nor, consequently, of any interest. His murder of an unfaithful girlfriend, illustrated by a hasty and artless flashback, seems the director's reluctant concession to our schooling by the "psychological" cinema: to pester fictional characters with inquiries about their past.

What if they refused to answer? Would we lose our interest or become twice as curious?

The mask does not chatter about its family circumstances, that's part of its mystery.

Just as silent is Hyun Shik, a suicide full of life all but pampered by it.

Shuttling the newcomer to his raft, Hee Jin grasps this at first sight. She already knows by instinct what she'll discover later on so tactfully: now with a furtive glance from a mooring in front of her house, now with a seemingly occasional "control visit" to the strange angler's raft, to bait the empty hook on his fishing line and, without betraying her presence, to glimpse him sob crouched in the cabin, with his head dropped on his knees and his shoulders shaking.

That's enough for her to divine the exact moment of an imminent tragedy, to dive under the raft when a gun is already at the suicide's temple and to stab his leg when his finger is about to pull the trigger.

From a sudden pain Hyun Shik will jump up with a yell and want to live again, while she will be already rowing back in silence. Any inquiries, let alone consolatory conversations, are categorically excluded: if for Hyun Shik a half-page of text can be scrapped up in the entire film, Hee Jin doesn't utter a single word.

For a while, her absolute muteness seems a clinical impairment. Further in the story, a single phone call she makes -- significantly, also a silent one, only seen through the window - upgrades a presumed ailment to a captivating interior trauma, with a generous windfall for characterisation.

"I reflected so much that I don't have anything to say", the Sphinx in Flaubert's Temptation of S. Antonio says.

Hee Jin must have suffered as much.

"Mute as a fish": Suh Jung playing Hee-Jin and Kim Yoo Suk as Hyun Shik render that verbal platitude moist and juicy like a fish just pulled out of the most fragrant depths. Even cinemato-graphically, a metaphor imposed with such persistence would soon become monotonous and cerebral were not the actors soaked with its physical plethora. Mute as fish, they paint with plasticity two inimitable human beings twitching on the hook.

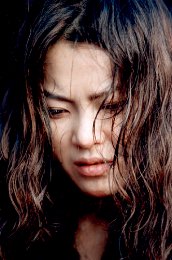

Take Hee Jin, decidedly down-to-earth, without a tint of sentimentality: proprietor and hard-working boatwoman; trader in food and fishing tackle; part-time healer of men's lust with her own body and a dutiful supplier of her full-time fellow healers. To abandon once and for all any romantic illusion on her account, just see her bite a worm in half, or kill a frog with one adroit whip of a rod and skin it matter-of-factly, as if peeling off a tight stocking. At the same time, there is something witchy about her, from the underwater realm: muteness, ability to dive and emerge- not an instant earlier or later than it becomes crucial, without a splash and without call - like the lake spirit or a fish used to air, or half one half another, or both...

She is everything but a tickling mermaid of romantic poetry. This one rescues with a stab of a knife and avenges an insult in cold blood. In the sweetest moment for her rude client, when he'll squat down on the raft's edge to empty his bowels, she won't balk on diving under turds, catching the shitter by arse and pulling him on the water. He is lucky to have fellow anglers around: otherwise, the mute mermaid would calmly watch his bubbles rise to the surface without moving a finger.

Pulled out, he will explode with maledictions and threats, but the mute mermaid will row deaf nearby as if nothing happened. Only a sullen joy of revenge will be glimpsed now and then in the avenger's eyes: well, next time the rascal will think twice before scattering his payment across the water, and will learn the price of her drying wet bills under a newspaper, while on the verge of flooding it from above with tears of rage and humiliation.

In a free minute, a leisurely swinging Hee Jin glances now and then at the cabin with the taciturn Hyun Shik inside, having no idea of her own simultaneous rebirth under his finger as a lonely wire figure on a wire swing. He twirls with pliers for no purpose what will come handy as a gift to his saviour when she'll dazzle him with a reflection from a tiny mirror, concluding her coy advances with a visit of courtesy.

Nothing substantial seems to occur yet the silence over an idyllic lake vibrates like a tense string. It is all but an easy goal to accomplish in such a placid environment, where only Hee Jin's boat plies unhurriedly between the anglers: those now fishing in silence, now making a routine quickie with umpteenth prostitute, and turning frenetic only when a fish bites at the apex of lovemaking.

* * *

Both solid and pliable, the narrative fabric weaved by the director is a sheer pleasure to pass between fingers. A resolute rejection of the word sharpens sight; the heroes' muteness is so eloquent that the gift of speech begins to seem useless if not outright harmful for human comprehension. Midday languor of Hee Jin fallen asleep in her boat; the mooring boat's thump against the raft; simple technicalities of the fishing; a touch of neglect in and around the owner's dwelling: this fond rediscovery of the insignificant in its unpretentious beauty becomes a gripping plot in itself, sometimes more powerful than the plot proper, now barely pulsating, now limping.

Well-composed and self-sufficient, the frame contains only the most substantial part of the action, without the habitual beginning-middle-end progression; what would be easily predictable in a commercially smooth editing with its "preparations" and "transitions" becomes a cascade of visual surprises thanks to a sacrilegious jump-cutting; a verbal trinomial transforms into a visual noun, an emblem or, to be geographically correct, a hieroglyph. In the western alphabet it would translate not as "Hee Jin sails away - floats by lake - moors to a raft," but as "Hee Jin in a boat at a mooring - on the lake - at the raft." That deletion of dead pauses from the image fortifies the remaining clear notes, interweaves them into a harmonious tempo-rhythmical pattern; episodes, resembling mini-stories or poetic miniatures in the haiku tradition, are perceptibly musical, complete and autonomous - yet moving the story forward as well; you'll not find there a single superfluous close-up or an excessively detailed behavior; the storyboard's niggardly stinginess produces enough expressive wealth to make envious a millionaire with a shoe-string imagination.

Well-composed and self-sufficient, the frame contains only the most substantial part of the action, without the habitual beginning-middle-end progression; what would be easily predictable in a commercially smooth editing with its "preparations" and "transitions" becomes a cascade of visual surprises thanks to a sacrilegious jump-cutting; a verbal trinomial transforms into a visual noun, an emblem or, to be geographically correct, a hieroglyph. In the western alphabet it would translate not as "Hee Jin sails away - floats by lake - moors to a raft," but as "Hee Jin in a boat at a mooring - on the lake - at the raft." That deletion of dead pauses from the image fortifies the remaining clear notes, interweaves them into a harmonious tempo-rhythmical pattern; episodes, resembling mini-stories or poetic miniatures in the haiku tradition, are perceptibly musical, complete and autonomous - yet moving the story forward as well; you'll not find there a single superfluous close-up or an excessively detailed behavior; the storyboard's niggardly stinginess produces enough expressive wealth to make envious a millionaire with a shoe-string imagination.

"In ballpark U.S. figures, what was the budget for The Isle?", Kim Ki Duk was asked at the Sundance Festival, "It looked to have at least several million behind it".

"$50,000", was the answer, "but this was possible only because we all worked without pay and for a part of whatever it takes at the box office."

In turn, only an absolutely trusted artist can count on such collaboration. Pleased to refresh his somewhat rusted Russian, Kim Yoo Suk playing Hyun Shik gave us a vivid perception of what an occasion to work with Kim Ki Duk means for a young actor. He studied in Moscow, at "Schiukinka", a theatrical school of the Vachtangovian tradition, one of the best in Russia, and his graduation work was Raskolnikov in Crime And Punishment. Today, he quite assertively enters among the leading movie stars in Korea. His next work is an expensive and well-paid domestic blockbuster (its mere mention gets coloured by a touch of irony modified by a nice mixture of vanity and modesty) - but The Isle is different. It's "for the soul", not for money. The actor recollected, laughing, how he insisted on giving Hyun Shik more biography and psychology - read "more text"- and how nothing, fortunately, came out of his efforts.

That conversation was in Venice.

But before...

* * *

"Few films produced in Korea have generated such a polarized response as The Isle. Most domestic critics abhorred the film, except for a few who gave it four stars. It bombed at the box office, despite an expensive marketing campaign. The film is certainly a mixed bag -- as for myself, I find it somewhat of an embarrassment," writes in his encyclopaedically exhaustive Internet page Darcy Paquet, historian and researcher of the Korean cinema.

He seems a worthy foe. First, a critic, who underlines his judgment's "hisness" deserves

a plenary absolution from all his sins to come. Second, he picks at the weaknesses which might prove real though not as overwhelming, and praises the merits not as marginal as he believes. Third, the ratio between his argumentation and the space allocated is highly efficient.

He seems a worthy foe. First, a critic, who underlines his judgment's "hisness" deserves

a plenary absolution from all his sins to come. Second, he picks at the weaknesses which might prove real though not as overwhelming, and praises the merits not as marginal as he believes. Third, the ratio between his argumentation and the space allocated is highly efficient.

Now, let the sinner confess at will.

"The Isle is nothing if not sensational. From early bits which make the audience squirm, the film gradually climaxes in some horrifying scenes of self-mutilation, which are nonetheless played for laughs by the director. The film is shocking, and it clearly anticipates moral outrage. Yet on dramatic terms the movie falls apart. The characters' actions seem driven not by any internal motivation, but rather the director's efforts to drive his story forward. The film strives to achieve some sort of dramatic symmetry, but its efforts are so obvious that at times it feels like a parody of itself. Ultimately the film is dishonest with its viewers, and so it is hard to take it seriously.

"The film is not without some strengths. Director Kim Ki-duk has a rare talent for color and composition; in fact, before coming to film he studied painting in Paris. All of his works feature striking visuals, which makes one wonder what he might be able to accomplish with a strong screenplay. Also of note is the strong performance by actress Suh Jung, who built her career starring in a series of experimental independent films.

"Ultimately, however, the film leaves the viewer with a sick stomach -- for its violence as well as its missed potential. No doubt The Isle will provide the people at Venice with a bit of controversy; it's just a shame they couldn't have picked one of the better films that this industry has to offer."

It was from Venice, however, that The Isle had taken off for a good half a dozen or so festivals: Toronto, Salt Lake City, Rotterdam and such, being often preferred to "the better films that this industry has to offer", with their incommensurably higher budgets.

There, however, the same story kept repeating: for one admirer, ten detractors.

Their indignation, of course, did not regard the skinned fish: innocent kids' stuff by comparison with the gory rest.

Should we tell in advance in what part of her body Hee Jin thrusts a cluster of hooks?

Told.

Now, let's avoid both spitting and laughing, as well as escaping from page: there was enough of that in screening halls. Instead, until the film reaches us - and such works should

reach everywhere sooner or later - let us watch the monstrosities whose credibility cannot be cancelled even by their monstrous unlikelihood.

* * *

Hyun Shik is not the only runaway on the lake.

From his cabin, he sees a police boat combing the lake for a thorough I.D. check.

Attempting to escape, some neighbour ends up wounded and tied up on the boat's floor.

The same destiny expects Hyun Shik: the scooter already points at his hideout.

Here arrives one of two episodes, which have split the illuminated cine-humanity in two unequal halves: one furiously jeering, another, immeasurably smaller, enthusiastically applauding the same gruesome action. Having no escape, Hyun Shik convulsively swallows a cluster of fishing hooks, tears them out together with mutilated tonsils and falls with a terrible rattle on a blood-covered floor.

As always in time, Hee Jin bursts in the cabin.

The policeman entering shortly after does not see anybody except for a woman cleaning the floor.

No sooner does he leave than Hee Jin opens the hatch where she had pushed Hyun Shik, grabs the fishing rod, pulls him out like a fish, inserts a wand between his jaws and begins to extract from his throat one hook after another. The most skilful surgeon would gape in amazement at a similar stunt, and should he survive a fit of envy, at the sight of pliers as the only tool that magician would call gravediggers before attempting anything.

The viewer's perplexity is more than understandable. An extremely harsh sight is but a pretext for it: sadomasochistic B-movies are full of worse barbarities. Here, we have a lot more than another of their cascades: taking so much word for word a metaphor about man's fish-like tenacity, the director takes on the sacred idol of our perception: the very idea of verisimilitude. The idolater has to adopt new faith, based on the belief in the unbelievable - or to hate its preacher. Such things have happened in history more than once, at every change of faith.

What normal man, already with a bird of hooks in his throat, will not take a fatal mouthful under water in an endless few minutes? What tonsils, already mutilated, will sustain dragging a heavy body on a hook, like a carp, without attempting to seize that mass by the collar? How is it possible to pull hooks out of throat with elementary pincers, without anaesthesia and disinfection?

What normal man, already with a bird of hooks in his throat, will not take a fatal mouthful under water in an endless few minutes? What tonsils, already mutilated, will sustain dragging a heavy body on a hook, like a carp, without attempting to seize that mass by the collar? How is it possible to pull hooks out of throat with elementary pincers, without anaesthesia and disinfection?

After all, these are tonsils, not gills!

Here is the whole point: these are gills, not tonsils.

In the moment of danger, some fish-sorceress must have given the hero her breathing, gills and tenacious will for survival: as a reward for suffering, silent meditation, feeling sorry for the skinned fish, for his very choice of the lake as the ultimate hideaway. All this bloodshed might well be just a metaphor, but the director is no mere fool to announce that; instead, openly enjoying our foolish consternation, he stabs us in the hip with physically impossible things, forcing us to forget the laws of gravity and fly headlong into... a fairy tale.

Yes, with no trace of policeman in him, Hyun Shik is a normal hero of a fable, dream, imagination.

Uninitiated in this secret, we cling to our habitual need for plausibility and clarity and, not finding them, don't realize that in this case such virtues would mean Disneyland or a romantic ballad. Instead, the fable we are watching is those genres' blood-chilling contrary, its environment banal and harsh, violent and painful.

To hide ever-bleeding flanks, the scales protecting them should be armoured.

Thus Hee Jin, fully fitting this description, is also from the fairy tale realm.

Her analgesic after a barbarous operation is the most curative female organ. Long before the advent of cinema, Gustave Courbet painted its close up and named it the Centre of the World.

Hardly the last hook has fallen in the bloody slime on the floor, that the sorceress of the lake unbuttons the trousers of a nearly dead Hyun Shik, sits over and gives him a gentle ride of love.

Life-giving Eros celebrates the victory over Thanathos.

Good reason for an idolater of plausibility to get beside himself: what sex could ever be possible with a near-corpse, what is he capable of, with his guts out? Instead of squeezing out last drops of his vivifying moisture, wouldn't an urgent blood transfusion be a sounder action to take?

By the author's poetic sexology, very different from the clinical one, the rescue comes only now. Hee Jin's curative caresses are an imperious order to literally revive from the dead, all members without exception, so that the healer has something tangible to heal.

This is a fable adult way. Antique myths are full of such intercourses.

Once, during an outpour, Hee Jin visited Hyun Shik, and both sat down at the raft's edge to share a bottle. The suicide visibly thawed to life began treating his saviour as a professional consoler. Nearly violating Hee Jin, he did not achieve anything. Leaving in his hands blouse torn to threads, a two-penny hooker demanded this time too high a price: love. Out of contempt for the client's health necessities, she even fetched him a prostitute from town, but didn't put for sale her pride.

Now, she gives herself up as a life-giving missionary, assuring with her formidable know-how something special to recall even in case of death.

Bordering on business-like, this erotic scene overflows with tenderness exactly because there is no trace of sentimentality. How much softer and, if you will, more timid it is compared to a normal commercial pic's exhibitionism! Here, the heroes are too shy to expose their feelings; there, the characters undress because they have nothing else to show; here, thirst for life is celebrated; there, a lazy itch of satiety.

How many sexual organs should one put together to satisfy the lust of sex shopkeepers?

Impossible to count.

* * *

Hammersmiths of Socialist Realism had forged a steel chastity belt over the lower half of the body.

Democratic Naturalism does the same to the top part and offers for scratching a brazenly exhibited, sweetly itching bottom.

One way or another, severed halves are not a whole person, and a dissolute itching is no substitute for a cowardly removed pain.

Obscenity and violence are becoming the delicacy of beau monde, a plebeian scandal at a refined reception distracts from increasingly scandalous scarcity of creative discoveries.

Who says art should be pleasant?

Certainly not, lest the unpleasant becomes disgustingly artless.

In the Portuguese film Phantom, in the same Venice competition, an insatiable homosexual masturbates with the aperture of a motorcycle fuel tank - and it is only, so to speak, an appetizer for an incessant backdoor penetration of his fellow assholes, (no offence meant, homosexuals can also be dumbbells), something like a half-dozen for a night; plus a socially useful job in the meantime: collecting and unloading at a dump the city garbage. By a curious coincidence, this hero is also wordless yet, by a fortunate disparity, he is totally brainless. Listening to that humanoid's moaning, oohing, ohing and ahing provokes first an irresistible disgust and, then, a fatal boredom: cinema whose only challenge is pulled-down pants proudly exhibits its bottomless stupidity, obscenity castrates intellectual faculties.

The last Berlin festival upgraded the status of artlessly scratched intimate parts by awarding a Golden Bear to a voyeuristic Intimacy where actors, because of scarce demand for traditional expressive organs, use only sexual ones. The actress' mouth is too busy to use lips for speech, the duet's essential muteness is strikingly different from that of Kim Ki Duk's heroes: one is a pretentious dummy run of love sterilized to coitus; the other condenses an enormous emotional and reflective pressure.

The funny thing about this bastardised Freudism, reduced to lowering pants, is its iconoclastic posturing. The discovery of genitals is presented as a new horizon of self-knowledge, baring one's behind becomes a rebellion on a par with revolution.

All but tormented by bashfulness, the last Cannes selection gives a telling scrap book of that no-risk insurgence.

"I do not suffer from conformism and do not understand what 'normal' means," a former ballerina, first-time director and protagonist of the film Clement declares.

An Italian female critic appreciates her determination: "Clement is the film-scandal of the Un Certain Regard section. By this courageous work Emmanuelle Bercot confirms the tendency of many French actresses to overcome borders of patriarchal timidity by accepting risky roles, such as a sadomasochist Isabelle Huppert in La Pianiste and lesbian encounters in Emmanuelle Beart's Repetition, to name just few random titles."

"You must provoke such a disgust in the viewers" -- was the Austrian director Michael Haneke inspiring his actress Isabelle Huppert - "that they wouldn't be able to look at the screen".

"I did my utmost to achieve that," boasts the actress who recently played Medea on stage, "and with this film I've overcome all the barriers. From now on, there is no part that would scare me."

A part more liberating than Medea? Who is that great creature?

A critic reports:

"An impeccable piano teacher at Viennese conservatory, fortyish Erica Kohut frequents a sex shop, excites herself by spying on young lovemaking couples in a drive-in and feels pleasure scratching her vagina with a razor blade. Onto a student in love with her, she imposes such extreme sadomaso rules that the game gets out of control."

This is an indecently well-mannered description of squandering two undeniable talents on a strictly private clinical pathology: an objective easy to reach by a minimally professional hack, i.e. producing disgust by presenting it to the best of one's incapacity.

Here is what Wayne Wang refreshes the Cannes menu with: "Irrigated with sweat, elaborate corporal exercises which Wang lets us peep at, endow the hero by the end with a full-blown sexual act and, pay for one take two, the heroine's masturbation."

Here is the same in another critic's summary: "The Centre Of The World, next scandal of the season: variations on a "taste of vagina" theme, anal coitus with urinating and so on in this vein".

Though sharpening their wit on 'scandals', critics yawn without them. Otherwise, they wouldn't have anything to write about. For their reader, long corrupted by onscreen sexomania, has more interest in a dirty piquancy than in artistic acuteness.

That chain is endless.

In expectation of new mind-boggling techniques, let us return to The Isle, where two human beings twitch on a hook.

* * *

Love is love yet work is work.

While another prostitute gratifies Hyun Shik, Hee Jin dies of jealousy serving another client. Diving under his raft and peering out of the hatch, she burns him with such a hateful glance that his lust withers at the height of lovemaking.

Next morning, when the prostitute pays her for transportation, Hee Jin throws the money back in the hated face. That doesn't stop the girl from coming over a couple of days later without invitation: a taciturn, surprisingly kind-hearted client makes a strong impression on the girl dreaming of marriage and normal life.

She'll pay dearly for that visit.

Passing by Hyun Shik's lodging, the vindictive mermaid carries the flabbergasted rival to a vacant hut, ties her hands and legs with adhesive tape, sealing with it her mouth as well, and tags the whole raft at a far-flung area of the lake.

It does not cross her mind that the victim might try to creep out and fall in water immobilized. When she intuits such an outcome and returns to release the captive, the tragedy has already happened. To eliminate evidence, Hee Jin brings the victim's motor scooter from the mooring and sinks it together with her.

In front of Hee Jin's house, the dog was howling all day through. It will get something to howl about in the night as well, when a new involuntary crime will fall on the lovers.

Infuriated by the prostitute's absence, her pimp comes to the lake, provokes a fight with Hyun Shik, gets an unexpectedly rough response, falls in water and drowns.

The pragmatic Mermaid takes care of this problem, too, by tying the corpse to an accumulator and sinking it beside the drowned girl.

No more swinging girls as a gift of love: the doomed Hyun Shik twists a wire scaffold with the same figurine dangling from it.

Consoling the beloved, she sinks that macabre prophecy and clings to the scared accomplice for consolation: he pushes her away.

Avenging the insult, she sinks a cage with two birds in it: avenging the revenge, he hurriedly collects his things to leave.

The mermaid jumps in the boat ahead of him and off she goes, leaving behind a helpless hostage: the angler fishing on an empty hook and releasing his catch cannot swim.

The mermaid jumps in the boat ahead of him and off she goes, leaving behind a helpless hostage: the angler fishing on an empty hook and releasing his catch cannot swim.

The imperious Mermaid's love becomes a chain; his dollish hut, a prison cell.

The inmate does not surrender: during the night, he cuts off a balloon from under his raft and tries his luck on it. Vain attempt: the balloon slips out from unskilled fins, the runaway begins to choke.

The omnipresent Mermaid is there again: a hook she throws to the fugitive and he grabs with a naked palm suffices to fish him out of death for the third time. Hee Jin's victorious smile is premature though: in gratitude for extracting the hook from his bleeding palm, Hyun Shik pushes her down and boots her on the crotch, beats her as ferociously and senselessly as he once chopped his meagre catch, beats with the same fury towards everything that renders the victim yet more unique and irreplaceable, beats in the same upsurge of impotence that can end only in total exhaustion, when the executioner falls between those same maimed legs and drowns his despair in a yet more desperate sex, wailing and weeping from pain. Terrifying indeed they are, two human bodies in lovemaking spasms, beating their heads and tails against naked boards like a fish under an electrode!

Based on a trite verbal analogy and advanced with an obsessive maximalism, one of the most powerful cinematic metaphors is unfolding: undeniable because unbelievable, fantastic because extremely prosaic, full of mysticism because sunk in mutilated flesh.

Laugh or fume at it, man is a fish on a hook, with life as bait on its spike. The Greek tragedy's fatalism speaking in a wordless Korean turns out to be universally understood.

Now separately, now together, two fish keep twitching on the same hook: no sooner one, devastated by beatings, falls asleep than the other creeps in her boat to ply his oars and to dissolve in the morning fog.

There is no escape though: the fugitive has strained the common fishing line, invisible yet so real!

To prevent a betrayal, nothing else remains to the speechless Hee Jin than to push between her legs a cluster of hooks and, wailing like an animal, tear them out. How can the fugitive, thrice wrought out of death by his liberator-captor now in agony, cut off their indissoluble bond and flee from that violent cry, while she, in her blood-soaked skirt, barely stands up and falls in water? Jumping on a platform, Hyun Shik has time to seize the rod and pulls her towards the raft like - yes, like an elementary big fish!

Attention though: wasn't something similar already seen earlier in the film?

Sure: Hee Jin had pulled Hyun Shik out of water with the same nonchalance. Conclusions of both "horrifying scenes of self-mutilation", as acutely observes Darcy Paquet, "are nonetheless played for laughs by the director".

If so, where is the problem? Intentional playing for laughs means exactly that: intention, not accident. Since an inbuilt comical detonator is hidden in the most chilling horror anyway, why not release its charge in a harmless controlled explosion? What is better way to protect true horror from slipping into gore than to draw between them an insuperable border of fun? Any clever child steps out of the most enthralling game if silly adult onlookers feign taking it, or do take it indeed, too seriously. The baby comforts them with a paternalistic assurance that this is just a game, and resumes it twice as intensely with whoever accepts that covenant. It has been accepted and beautifully expressed by greatest cineasts as well: all Hichcock thrillers are permeated with a subtle irony towards their horrifying events, a brilliant mind is inseparably fused with strong emotions.

Kim Ki Duk works differently but towards the same ends: he alternates one with another. By breaking poetic spell by briefly exposing its mechanics, he assures a redoubled involvement immediately after. Better to undercut poetry now and then than to let the viewer ridicule poetics.

You're welcome to giggle or split your sides from laughter because your flippancy will fade away the very next moment, as soon as Hyun Shik will dive headlong between Hee Jin's blood-smeared legs and will begin to pull out hook after hook from the mutilated vagina, exactly like she pulled them out of his throat. All but the lack of dramatic symmetry: his own rescue is mirrored in hers verbatim, action by action! The only thing lacking is sex therapy. Then, love was conceived on the brink of death. Now, it is being born in the deliberately anti-aesthetic slime of a mutilated womb. In its bloody marriage with Eros, Thanatos has begotten a baby: true tenderness between the lovers.

Again and again: always watchful not to fall into the trap of sentimentality, the director amuses us with another ironical and teasingly symmetrical undercut: exactly as Hee Jin accelerated the healing of Hyun Shik's mutilated throat by fixing his mouth wide open with a spreader stick and fanning it, now Hyun Shik performs the same folk medicine trick in front of her lacerated crotch! What a feast of unblemished filth or, if you prefer, of brazen bashfulness!

Why, then, do the tragic scenes cause so numerous protests? If an unpleasant sight is the only problem, should we not renounce then the bulk of world dramaturgy as well?

Its atrocities open with Oedipus' empty eye sockets. From there, flows out in blood and tears an everlasting dramatic tradition: to test a human being with inhuman pain. From Oedipus' pricked out eyes it arrives over the centuries to the blade slashing a calmly blinking eye in Le Chien Andalous by Bunuel & Dali. Although tragic pathos of pain is anaesthetized there by defiant buffoonery, no matter how many courses of blood and guts would have splashed from screen and how frenzied the race of brutality would have grown since, cinema does not offer anything remotely as powerful as those two samples.

The Isle is close to one in showing the self-mutilation of a wholesome yet morally tantalized man, and the film's severity is at least equal to the second.

Beyond either of the two, there also is a typically unclassifiable and decidedly humanist talent.

Kim Ki Duk's hooks are as sharp as the Bunuel & Dali razor in the eye.

* * *

We meet the director during the festival and ask whether he saw Le Chien Andalous. No? Then, he does not know the razor cutting a healthy eyeball?

Kim, intrigued: "But this is from my next film!"

Ancestors stealing from descendants?

When both are talented, it happens.

Although Kim's unawareness of such classic is a rare thing in his country. The already quoted Darcy Paquet writes:

"Korea has been referred to by some as the most film-literate society on earth, and the Pusan festival is the premier venue to witness this in person. The audience at the festival is ovewhelmingly young -- it seemed that 95% of the crowd was under 30 -- and generally well-informed about film. I've read that visiting directors are often amazed at the challenging questions posed to them at screenings and press conferences."

Reckless energy of the South Korean cinema tiger that daringly grins his fangs at Japanese and Chinese counterparts is a painful hook in the throat of the Ukrainian artificial infertility. To avoid agonizing envy, this theme is better not to touch. Still more painful to us is to read about decisive support given to that country's industry both by the state and the viewer. This was crucial for a true explosion of young talents: a whole generation grown up in the nineties. Kim Ki Duk belongs to those favorites of destiny.

Born in 1960, North Kyungsang Province.

1995 - Awarded by Korean Film Commission for the script "Imprudent Pedestrian".

1996 - Crocodile, directorial debut.

1997 - Wild Animals, scriptwriter, producer, set designer.

1998 - Birdcage Inn

2000 - The Isle

2000 - Real Fiction

2001 - Address Unknown

2002 - Bad Guy

Not bad at all for a marginal, non-commercial artist: a film every year!

A film every year - remaining marginal and non-commercial!

It would be interesting to talk with the director seriously and freely, let the conversation flow around his Isle like a river, switch from his life to his painting, and from the complex tissue of his film back to its real-life sources. Alas. Festivals, with their flash press conferences and frenetic interviewing schedules, are the worst places for such Utopian ventures. Our ten-minute interviewing slot has expired; heavily armed with TV equipment, members of the State TV crew are tapdancing around impatiently.

The last question comes out totally unanticipated, from a fleeting glance through the lobby's glass wall:

"What does this seascape evoke in you, Kim?"

The last question comes out totally unanticipated, from a fleeting glance through the lobby's glass wall:

"What does this seascape evoke in you, Kim?"

The sight was extraordinary indeed. As if burst free through the projection canvas, a menacing wide-screen sky has expanded to a cosmic one. A meteorological whim became angry Heavens ready to crush the festival bazaar, to wipe off its stands, from makeshift plastic ones to concrete bunkers.

A hurricane was ripening. The sky's blackness was growing angrily bluish; a turbidly green sea under it, on the contrary, turned into a boiling green amber, pierced with light from within and covered with white manes of invisible galloping sea horses. Not a single boat in sight, not a bather on the beach. Only on the horizon, exactly at the splice between the apocalyptically bluish sky and the lapis-lazuli sea, sparkled a dazzling-white yacht, abandoned by an absent or careless owner. The festival's bustle has grown quiet and humble under the majestically virgin Universe, divided in two halves as if at the beginning of Creation. The Firmament and the Abyss: apart from the difference between the sea and the lake, almost a quotation from The Isle.

Surprised by not-quite-a-journalistic question, Kim looked at the seascape for a while. Then, answered as if asking for a confirmation:

- Solitude?

* * *

We swear on the Bible seeing exactly that: a piercingly painful film on solitude, and what a solitude: pitch dark, voiceless and suffocating solitude of man in the universe.

Why, then, its most desperate and terrifying expressions provoke disgust in thin-skinned viewers, laughter in more hard-tempered, and by no means all the cinema gourmets savour the treat? Could it be that the director himself has swallowed too deeply the hook of his leitmotif?

To begin with, he has no alternative. A disciplined artist listens only his material's will. Hooks pierce the film's entire flesh, and developing this motive up to the most drastic extremes is his unrenouncable duty. It takes a lot of courage, no doubt. Polite but firm, the artist says to the spectator: "Here will be things unpleasant for you, but I am obliged to show them." The average audience, however, reacts to drama like to an amusement park's "room of horrors": first, recoils; then, comes to oneself; finally, curses or laughs.

An answer to an inevitable "why" might be in the disproportion between the characters and the torments they suffer: the former are just too small for the latter.

An answer to an inevitable "why" might be in the disproportion between the characters and the torments they suffer: the former are just too small for the latter.

The director's healthy sadomasochism does not sustain the cruelty of an exacting dramatic structure. With three corpses on the record and the only concern to hide them better, Hyun Shik and Hee Jin can hardly pretend the viewer's total participation. Sympathy, yes, but the tragic catharsis, no: for that, both heroes are neither sufficiently noble nor adequately diabolic. Out of three corpses, only that of a Hee Jin's rival prostitute is justified by the Mermaid's jealousy. That of Hyun Shik's unfaithful lover is no more than a faceless entry in his criminal record; and the angry pimp's drowning declassifies him from a wicked character to a fool: given his clientele's environment, a guy just a touch smarter would certainly take a few swimming lessons, to begin with. The pimp's corpse serves just to make ends meet: a necessity, tragically acute for the narrator yet too petty for a tragic narrative. Moreover, a stricter scrutiny of plot intricacies brings about another unpleasant discovery: it is not a gnawing remorse for murdering his beloved that makes Hyun Shik swallow hooks, but elementary fear of arrest! Isn't cowardice too petty a trait for a presumed Oedipus the King's kinsman? Alas, his monstrous self-punishment is built upon a flimsy groundwork. Kim Ki Duk the scriptwriter trips up his namesake the director. To the credit of the latter, we notice that only retrospectively, thanks to a sumptuous cover-up of a strong plastic development and excellent acting.

In a more constrained and lyrical key - let's call it "a skinned fish crying in silence" - both protagonists are expressive, full-blooded and irresistibly human. Paradoxically, the problems begin when the society leaves its alleged outcasts in relative peace. Only then does one discover that nobody but Hyun Shik and Hee Jin themselves, hungry for love yet incapable of loving, keep skinning their own and each other's flanks. Hence sex as a drug. Hyun Shik's desire to escape and Hee Jin self-mutilation are typical drug addict's reactions: a swift detoxication and a hysterical thirst for a new dose. With mysterious masks barely off, faces behind them disappoint by their ordinariness, two mutes overshout, fountains of blood spew from suddenly anaemic characters.

So, the film's vicious critics are right in their categorical rejection?

To a certain degree, not more. Unattained tragic greatness renders the protagonists, in a way,

more familiar and moving in their real-size smallness: so easily recognizable human fish in distress, gnawed by the inner pain more atrocious than a physical one! Not taking it seriously seems a bit snobbish. As a Chinese proverb has it, a limping lion is still a lion while an impeccable fly is only a fly. The tortures to which the director sentences his creatures are not a gamble but an honour to aspire to, a passionate bid to deserve them.

As to expressive potential of physical violence as such, a sharp contradiction tears apart scores of films based exclusively on that concept.

Just what is that contradiction?

To answer, one has to ask.

* * *

Apart from easily imitable and pleasant-to-perform hedonistic extremes, is extreme physical suffering attainable at all, especially in supernaturalistic cinema, which thrives on a meticulous imitation of the most horrific atrocities?

The question sounds outright ridiculous: there is nothing inaccessible for cinema.

Not quite. A more thoughtful answer might be shattering: the more trustworthy is an imitation of atrocities the less believable they grow in the end.

From a superrealistic viewpoint, nobody has managed as yet to burn out convincingly Jeanne d'Arc or to blind Oedipus, while a crucified Max von Sidow in The Greatest Story Of The World provokes a pitying smile: too immense is the distance between the real Messiah on the Cross and a monkishly diligent parroting of his torment.

Otherwise, for the sake of a 100% coherence (and without it, the spectator's initial trust precipitates into mockery or irritation), the authors would have to quarter, to crucify, to burn, to hang up and to drown actors really, to cut their heads and to prick out their eyes indeed, while the horrified viewers would rush in frocks towards the screen to prevent the barbarity. In short, the more spectacular violence on screen is the more it comes at loggerheads with the very idea of spectacle.

Otherwise, for the sake of a 100% coherence (and without it, the spectator's initial trust precipitates into mockery or irritation), the authors would have to quarter, to crucify, to burn, to hang up and to drown actors really, to cut their heads and to prick out their eyes indeed, while the horrified viewers would rush in frocks towards the screen to prevent the barbarity. In short, the more spectacular violence on screen is the more it comes at loggerheads with the very idea of spectacle.

Naive conventionality proves equally disappointing. However fruity be the Voice of the Almighty in a recent TV adaptation of the Bible, feigned tremor of an utterly cartoonish Moses on screen will reverberate in you only as an earth-shattering laughter. The distance between this artistic primitivism and the creeps the real prophet should have had is as immeasurable as that between God and an ACTRA member working for union pay. Falsehood is the child of talentlessness, and its midwife is the belief in the spectator's stupidity. In a rigorously imitative cinema, the fire under Jeanne d'Arc grows all the more chilling the more brushwood it is fed with. So, by no means everything is accessible to cinema. With non-materiality of the image as a unit of measurement, an engraving or a painting will reach higher emotional temperatures; poetry and music, respectively, the highest.

However understandable, a burning desire to express inner suffering through physical torments is hard, if not impossible, to attain on screen. Otherwise, cinema would have long shaken the world with a tragedy "Boiled Lobster". Nobody has mastered as yet this blood-chilling plot. This is especially puzzling, since on the set you can do whatever you want with that apparently menacing yet totally defenseless creature. Still, even there, its expressive potential is limited to the realm of cooking: though easy to boil, showing what the poor thing feels as it boils will take a lot of takes, and none of them is likely to be of use.

Their tender flesh scourged by the scalding water; tossing about in despair between the red-hot walls of the armour suddenly transformed from an impenetrable cool shelter into a hermetic furnace, with not a crevice to escape through, millions of agonizing lobsters stand up in a deadly delirium on their steely tails, knock out the saucepan lids from within, sink their claws in our throats and, pulling us into a volcanic broth for the company, prove beyond any doubt that we'll hardly ever see on screen real pain, that its most skilful imitations are incomparable with our inner hell, inaccessible to the eye and human cognition and, exactly for that reason, more homely to our imagination than incorporeal paradise. Blood is painless and numb to pain -- it is the bleeding flesh that yells about its invisible torment through manifest slashes.

Doctor Zhivago believed that the soul in a body is as material as teeth in mouth, but a silly fancy to prick it out from teeth had never crossed Pasternak's mind.

Gabriele Salvatores, an Oscar winner, has recently done exactly that. His Teeth, after a Domenico Starnone novel, were grinning in the same competition with The Isle.

There, physical pain is also the pivotal theme, although with a huge abscess of intellectual pretence. Incurable as it is, its symptoms might be interesting to examine.

* * *

Antonio, philosophy professor of about forty and father of two children, has forsaken them both and their mother in favor of younger Mara. As she hangs about with suspiciously numerous friends, he stages an ugly scene and calls her a whore.

She pays back flinging a crystal ashtray on his teeth. Two ugly incisors that torment an otherwise pretty Antonio since childhood, break.

Seems a nice occasion to get it over with but, paradoxically, those same horse jags bring the man also a bitter enjoyment: his memories are settled in his gums. A light touch evokes his late mommy who died young. Now, returning, she fondles her sonny again and continues giving advise; another touch brings back his early sexual fantasies; yet more licking revives his uncle sea captain, with his collection of his lovers' pubic hair and the lessons in cuddling up to women in a tango; then, a mute

dental technician hews in pieces his beloved and beautiful wife, for no other reason than to deny her to anybody else, and so forth in this vein.

To get rid of his ghosts, Antonio runs from one dentist to another, just to realize their monstrosity. Drills buzz; hammers and chisels tap, rap and blow; artificial jaws click and clack; dentures crammed in mouth deform the patient's face in an ugly mask; yet all of that bounces back like wrong size prosthetic appliances; an evermore frenetic hustle provokes but a growing sluggishness. Finally, Mara's most unsympathetic friend - clearly, a dentist - does what could be done at the very beginning: pulls out goddamned incisors and feels underneath dairy teeth. Antonio's rebellious "stomatologic memory" gives him a break, but Mara, sick and tired of his scandals, abandons him, and the finally free philosopher decides to be just happy, whatever it means. Not much, in fact: a revived sonny meets mommy on the Tiber's bank and dances with her a lifelessly chaste tango.

Meeting dead parents; childhood memories of a beautiful mother; the awakening of an adolescent sexuality; searching for harmony in one's chaotic adult life: all that and much more has been seen in Fellini, but how strikingly different, how intelligent and poetic! 8 1/2 stands to Teeth as Pasternak's "soul like teeth in mouth" to Salvatores' involuntarily farcical "soul in tooth ridge". The issue is not thematic hierarchy, but an infantile development of a perfectly workable theme. Barely grown dairy teeth try to crack its nutlet in vain, x-ray shows their short and weak roots, and the film's feeble gums just cannot munch on anything resembling a meaningful reality, however stylised or subjective.

Meeting dead parents; childhood memories of a beautiful mother; the awakening of an adolescent sexuality; searching for harmony in one's chaotic adult life: all that and much more has been seen in Fellini, but how strikingly different, how intelligent and poetic! 8 1/2 stands to Teeth as Pasternak's "soul like teeth in mouth" to Salvatores' involuntarily farcical "soul in tooth ridge". The issue is not thematic hierarchy, but an infantile development of a perfectly workable theme. Barely grown dairy teeth try to crack its nutlet in vain, x-ray shows their short and weak roots, and the film's feeble gums just cannot munch on anything resembling a meaningful reality, however stylised or subjective.

The protagonist's horrors fail to scare or amuse, since neither pugnacious Desdemona nor gap-toothed Othello have brought anything spiritual to their wedding altar. As to a supposedly comical portrait gallery of dentists, bearded anecdotes about boorish waiters and foolish policemen are just as funny.

With his incisors broken, Antonio's pronouncing Shashary instead of Sassari (an Italian town) could trigger a lot of mirth if he rechited thish way hizh entire inner monologue - but what shelf-reshpectful European intellectual would dare ridicule hizh rebellioush shoul shtruck between hizh teeth, thush admitting that a shimple toothpick would shuffishe to liberate it?

Already punished enough by the critic's embarrassed silence and the public's indifference, poor Teeth should not have been punished additionally, by an analytical review, had not thousands of identical Jaws clicked greedily all around the world, and their artistic cavities were not so identical, stenchy and widespread - so globally that at time a random masterpiece seems an accidentally mistaken nonsense.

A comparison between the marginal Korean and the acclaimed Italian is not so much; that of personal ups and downs (who doesn't have them?) as of two opposite approaches to the same creative issue and their respective impact.

Kim Ki Duk keeps his anti-aesthetic anatomy at a certain distance, leaving a lot to imagination; in Salvatores, bared teeth in sanguinary saliva are an importunately central image. His philosophy teacher incessantly talks over no sooner than he shuts up in frame - yet there is little to listen to; a taciturn Hyun Shik arouses interest the more the longer he remains silent. On the voltage of biological pain, Salvatores aspires to soar towards existential summits - alas, in vain: the complete man has already become an appendix of his overgrown single organ or, as our ancestors would say, member.

Permanently open in fear and pain, the hero's jaws swallow all visual fabric of film, become its unique interior and exterior where plot, characters and action disappear one after another.

The latter reduced to a mere dental treatment, it is a dentist's undisputable realm, there is precious little to do for an artist.

Remains only to observe how far this disintegration of the whole man will reach. Isn't that why he disintegrates in life as well?

Kim Ki Duk's extremes give some hope. Whatever the handicaps might be, his man is not a simple sum of organs.

* * *

A detective story concludes - and notably undermines- the intended tragedy.

For just a moment, it seems that Hyun Shik's and Hee Jin's tribulations are over, and the longed for inner piece settles in both tormented souls.

Lo and behold: how lovingly the man combs his woman's hair and decorates it with a flower; how merrily they repaint their hut in a dazzling yellow, and their brushes soaked with sun intertwine like fond palms - but the calamity is already in the offing.

The stocky angler's new call girl takes a fancy to the most remote hut on the lake.

While fishing, he takes off and puts his Rolex on the raft's edge. Sharing his hunting ardor, the girl moves near too briskly and pushes the watch in water.

The victims of Hyun Shik's rage and Hee Jin's jealousy are under the same raft.

Having rewarded the scatterbrain with a slap, the angler calls the divers.

Hee Jin and Hyun Shik notice them already at work.

A pragmatic Mermaid drowns her boat, reattaches its motor to the raft, weighs anchor, and the dazzlingly yellow love nest, its door curtain fluttering in the wind like a banner of hope, floats in the suddenly endless, sea-like blue of the lake. Invisible inside the hut, two criminals in love are too beautiful at this moment not to be absolved. At least their creator will never imprison them, no matter what the plot dictates. He'll better send plot to hell and plunge instead into a shamelessly unrealistic ode to joy, rewarding his fleeing favourites with a fabulous honeymoon trip. A tiny isle of love dissolves in the sea of happiness.

Once again, something absolutely improbable. A happy end of a finally admitted fairy tale. A miraculous deliverance from banality. Pure poetry.

* * *

The director: "The Isle is vulgar and violent, but I wanted to make it tense and beautiful."

He's got it right.

There is not, however, a tiniest Isle on the Lake. Where does the title come from?

The answer is in the allegoric epilogue.

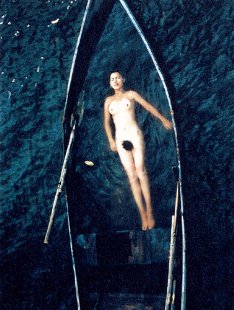

Just recently hydrophobic, Hyun Shik suddenly emerges from water. Refreshed and renewed enough to appear reborn, he looks around in the morning haze and wallows in the reeds. Growing ever smaller, the reeds' thicket becomes a clearly outlined islet in the boundless lake: something like pubic growth. Hyun Shik gets lost there.

Far away from him, dead Hee Jin lies face up in the sunken boat. A floating plant has stuck to the naked girl's perineum. Why dead, why naked? Because: an answer to which only poetry is entitled.

Beauty's logic is very different from a psychological down-to-earth motivation.

Why a floating plant?

Why a floating plant?

This is an easy one: nothing but a substitute for a figue leaf.

To avoid the public's carping. For the Korean public opinion, women's including, still considers this part of the body disgraceful.

The director: "We dream to rest on an island yet we try escape from it as soon as we get bored. The woman is the man's island, and vice versa. Though the drama of love often becomes obsession and fury, it also gives us force to live".

Even less simplistic "letters of intents" are usually colourless and harmful for a live work.

However, such "translations" are hard to avoid in the world with an inexorably decreasing live substance, ever more rarely recognized and understood. Like in this case: while the director aspires to a parable even in a summary, the viewer needs a ready made information block - extremely simplified, not compelling to think nor to feel pain. The globalised Middleman swallows entertainment in cyclopic quantities and without chewing. What hooks can hurt a similar throat? The planetary Movie McDonald's vigorously processes art into a quick snack, reduces an aesthetically sensitive human being to teeth and stomach, renders the entire globe a remote province. A quickly advancing totalitarian regime of dullness eats away live colours from life and substitutes them with garish paradises out of tourist brochures. Only incorrigibly talented artists can resist that massive attack.

Kim Ki Duk's artistic roots are in that dangerously dwindling camp. The Isle has all the prerequisites for a masterpiece except perfect harmony, yet all its flaws combined, real or presumed: lack of symmetry, logical contradictions, some dramatic setbacks and what have you - are a diary of a daring and risky exploration. Its every entry is truthful and piercing, to every touch of life respond fearlessly bared nerves, insensitive only to the industrial painkillers and woven from pure pain filaments, the artist's most blissful torment and most tormented bliss.

The spectator grown up on a pleasant tickling has evident problems with this kind of art. Its uncompromising practitioners have problems with such spectator. Their reciprocal need of understanding might bring the opposites together. The only thing needed is a tragedy "Boiled Lobster". Kim Ki Duk's skinned fish is an encouraging step towards it.

Following the film's international recognition, his native audience is likely to grow, too, although for now, a prostitute is frowned upon in Korea, even as a screen character. Feminists attacked the film with such a woman as protagonist, and by no means a negative one.

Surprised by such chastity against a background of child prostitution and widespread pornography, the director has suggested nationwide discussion.

The theme is impassable as a reed thicket: on human person and life as such.

Enough for an entire life.

* * *

Today's cinema faces a crucial dilemma.

Pain or itching. One or another. The middle point in art is external to art.

Although who knows.

Art has a nasty habit: it escapes measurements.

Rome, May 2001

The authors thank Darcy Paquet, researcher of the Korean cinema, for his generous consultation in preparation of this material.

Born in Kiev, Leonid and Larisa Alekseychuk worked at the cinema and TV studios of Kiev, Novosibirsk, Moscow and Leningrad, where they wrote and directed a host of films and television programs.

Such films of theirs as "Northern Sketches","Leningrad Ballet" and "Alice" were awarded at the All-Union Festivals, and others, namely "The Song Of Igor's Campaign" and "The Heart Of Polichinelle" were banned and destroyed by censorship. Among their major works for television to be mentioned were screen adaptations of Irving Stone's "Lust For Life" and Graham Green's "The Quiet American", plus numerous telefilms and programs of stylistic research in all genres, from the variety and art programs to documentaries. Bringing dramatic intensity into documentary works, bold visual experimentation in soundstage-based programs and fusing into an organic unity the genres considered incompatible has become the team's stylistic trademark.

In "The Heart Of Polichinelle", for instance, a documentary footage on the rebellious choreographer Leonid Yakobson was interwoven with a dramatic storyline of Polichinelle, Yakobson's choreografic character transformed into his filmic alter ego. Alas, the stylistic blend, which offered an interesting new prospective for the art documentary genre, was branded by the authorities "a gross deviation from the principles of Socialist Realism", and the film was destroyed upon completion. The blacklisted authors were forced to leave the USSR for good.

More than 15 years had to pass before "The Heart" was restored in Italy on video, thanks to the timely salvaging and secretly preserving workprint outtakes, and had its world premiere at the 1993 FIPA (Festival International de Programmes Audiovisuels) in Cannes. The work was acquired and broadcast nationally by the RAI TV corporation, but still not in Russia. Moreover, their script "Murder Of A Clown", based on Polichinelle's adventures in the USSR and in exile and put into production by the UK Central TV, was sabotaged in the full swing of "perestrojka" by the same film bosses who, now recycled as democrats, had destroyed "The Heart Of Polichinelle."

In the West, starting their careers practically from zero, with not a strip of film to show, the Alekseychuks wrote and directed a documentary "Letters In An Unknown Language" for TV Ontario; wrote, directed and produced a 20-part series of shorts for CBC and Radio Canada entitled "The Midsummer Sketches" and an hour-long adaptation of Alexander Pushkin's "Mozart and Salieri", realized at Leonid's Directing Class at the NYU Film Institute, where Larisa taught Editing and Leonid was a faculty Associate Professor Of Directing, Scriptwriting and Production.

The film was presented at the 1987 Montreal Festival Des Films Du Monde in the Cinema Today and Tomorrow section.

A few years ago, they visited their native Ukraine and shot an hour-long documentary "There is a Ukraine beyond Chernobyl", released by the Orbite 2000 Network and acquired by the RAI Television.

In Italy, where the couple reside now, they have held their private Intensive Courses of Directing and Scriptwriting, and Directing Workshop at the National School of Cinema. Leonid has also taught a scriptwriting course at the Gregorian University's Centre of Communication, and both are invited to teach, this coming fall, a Master Class at the Milan School of Cinema.

During the same period, they have also written a lot of criticism in USA and Canada for various publishers and broadcasters. As soon as it became politically possible, they began to publish in Ukraine: feature articles on Fellini ("Fedrico Fellini's Full Moon", "Black Peacock In A Snowfall"), on European cinema plus regular yearly reviews of the Venice festival.

Their extensive monographic article "Warrior In The Field", on Serghei Paradzhanov, was published in "Sight & Sound", and a theoretical essay "True to the Art", on the still picture's unexplored expressive potential in cinema, in monthly "Cinema Canada".

Dividing their time among all the above mentioned activities, the Alekseychuks are also developing a few feature scripts in Italian and English.

Larisa and Leonid Alekseychuk

Citizenship: Canadian

Present residence: Rome, Italy.

Tel/fax 0039 06 588 10 25