2004 Cannes International Film Festival Report

by Darcy Paquet and Paolo Bertolin

Darcy Paquet

This year marks my first ever trip to the Cannes Film Festival, which is now in its 57th edition. With two Korean films in competition, it was an interesting time for a Korean film fan to be in attendance. Alas, I was not there simply to watch films, but to work -- my job was to report on the Korean and Japanese film industries for the festival dailies published by Screen International. For the curious, I'll give a rundown of what that work was like before discussing the festival as a whole.

Screen, based in London, is one of the three major international film trade magazines, the others being the U.S. magazines Variety and Hollywood Reporter. For each day of the festival, we published a free special edition of the magazine ranging from 70-100 pages. A lot of those pages were taken up by advertisements or reprints of articles that appeared in the weekly magazine in previous weeks. The rest were filled by film reviews, profiles, or -- my responsibility -- news.

There was a lot to write about. Apart from the festival proper, Cannes runs a film market where international sales companies try to sell their films to distributors from other countries. Cannes is one of the world's biggest film markets, so there are a lot of film sales to report. During this year's festival, for example, Taegukgi and Old Boy were sold to North America, Bunshinsaba and Fighter in the Wind (both still in production) concluded multi-million dollar sales to Japan, and new projects by Kim Ki-duk and Jang Sun-woo were announced. Companies also like to wait and announce major news at Cannes, because they get much more publicity that way. One of my assignments was to write about a new Japanese financing company launched by Taka Ichise, the producer who made Ring, Dark Water and Ju-on: The Grudge.

Screen sent about 30 people in total to the festival: critics, reporters, editors, photographers, advertising representatives, etc. On a typical day I would go to Screen's temporary office, set up in the Carlton Hotel, by 8:30am. At 9:00 we would have a news meeting, where each of us would tell our news editor what stories we had found to write about. From then until the print deadline at 4:00pm, I would write those stories and/or stroll through the market talking to the companies set up there, seeing if there was any other news to write about. Occasionally I would meet with people for formal or informal interviews, or go to press conferences. After the day's writing was done, I would either rest a bit, go to a party/get-together to talk to people (where you would often get tips about news stories), or watch a movie. By the next morning the magazine would be out, and we would all read through it, while also checking out what Variety and Hollywood Reporter had written in their dailies (hoping you hadn't missed a major story that the other magazines had all picked up). And then the whole process would start over again. In total we published nine daily issues.

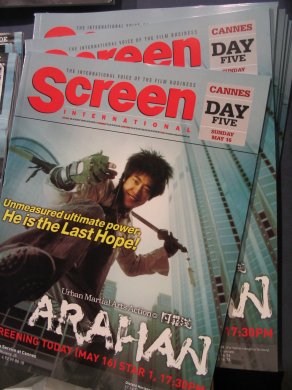

Day Five, Screen International Festival Daily.

Two of the dailies featured front-page advertisements taken out by Korean sales companies, which costs quite a fair amount of cash. Of course, when you're marketing a multi-million dollar film, and an advertisement can potentially attract a buyer who will pay upwards of a million dollars, then ten or twenty thousand dollars has to be put in perspective. Incidentally, the Korean Film Council (KOFIC) also provides financial support to Korean sales companies to help them take out advertisements like this. Day Two also featured an ad by Mirovision with a poster for Ahn Byung-ki's Bunshinsaba.

Our office, a converted art gallery in the Carlton Hotel.

Screen also published special sections devoted to many of the major filmmaking territories like Japan, Hong Kong, Spain, Scandinavia, etc. I wrote the South Korea special section several weeks before the festival, and it was published as part of the Day Three magazine. It basically consisted of six big essays devoted to new trends in film distribution and production, new film projects, influential people in the industry, rising stars, etc. Some of the photo captions got screwed up, and I missed a few things, but otherwise it came out all right.

The Korea Special. I'm not responsible for the bad pun in the title.

(click on the photo to read this page).

The festival itself was filled with noise, glamour, and activity. Virtually everything takes place on one long seaside street called the Croisette. At the end of the street is the Palais de Festivals, a large building which houses the Grand Theater Lumiere (and the famous red carpet leading up to it) as well as several other theaters of various sizes. Each day and night, big crowds would form near the theater to watch the VIPs and stars going up into the Lumiere for the main competition screenings, as well as selected out of competition screenings, which this year included Troy, Dawn of the Dead, and Hong Kong director Johnnie To's Breaking News, among others. Films from the festival's other sections -- Un Certain Regard, the Director's Fortnight, or Critics Week -- screened in other theatres to considerably less press coverage.

The Palais des Festivals at a quiet moment.

I never did make it into the Lumiere. In order to attend one of the fancy gala screenings, you need both a festival pass (which I had) and a ticket (which I did not). One can't simply wait in line and buy a ticket, unfortunately -- Cannes is very much an insider's event, and low-level press people like me had to obtain tickets through some sort of insider connection, such as through the film's sales agent. (I found out later that regular festival guests had other ways to get tickets, but those didn't apply to me) You also needed a tuxedo, which in the end was probably more of a hurdle for me than obtaining a ticket. A mere suit won't do; the dress code is quite strict. Rental shops are available to lend out tuxes at outrageous prices, but with so much else going on, I never got organized enough to obtain everything I needed to walk the red carpet.

Press screenings were much more accessible. Each film in competition had one or two press screenings, and if you had a press pass you just had to line up outside the theater to see if they would let you in. This being my first year, I had a blue pass, which doesn't rank very high up in the overall heirarchy. Nonetheless, there were usually seats still available after all the white and pink pass holders had been admitted. In this manner I was able to see the competition films Nobody Knows (Japan, dir. Kore-eda Hirokazu), La Nina Santa (Argentina, dir. Lucrecia Martel), Innocence (Japan, dir. Oshii Mamoru) and Old Boy (which I had already seen several times in Korea).

The side of the Palais, where press screenings are held.

(Cannes had a particularly ugly poster this year)

Aside from Old Boy, my favorite of that group was probably Nobody Knows. It's a film that requires a lot of patience, but I found it quite moving. It's based on a true story about a mother who leaves her four kids in a Tokyo apartment with an envelope full of money, and then several months pass... The movie is smooth and measured on the very surface, but it has a slow-building, quiet outrage that is very affecting by the end. Most people I talked to really liked it, though it is very long and requires a bit of effort on the part of the viewer.

La Nina Santa ("The Holy Girl") was another film that required concentration from the viewer, which many of the international critics apparently didn't have (in general, slow and difficult films did not score high marks with the press corps). The film centers around a 16-year old girl, her single mother, and a married doctor visiting a conference. The doctor starts to get close to the mother, but one day in a crowd he also touches the daughter in a sexual manner without realizing who she is. What sounds like the basis for a highly dramatic story is actually the opposite -- the daughter decides she must save the doctor from sin, and most of the film is focused on the subtly changing emotions of the three leads. The director described her film as a tale about "the difficulty of distinguishing between good and evil."

Japanese anime Innocence is a sequel of sorts to the director's famous Ghost in the Shell. Much like the Korean film Wonderful Days, it mixes 2D and 3D imagery but to a much different visual effect. The film is set in 2032, when humans and cyborgs co-exist in an increasingly close symbiosis. Highly philosophical in tone, the film devotes a large part of its running time to discussions about the meaning of what it is to be human or non-human. Sadly, I was really exhausted the night I watched this, and the seats in the Salle Bazin were quite comfortable -- so I only have a sketchy memory of the last third of the film. I'd really like to watch it again someday -- this is (again) a difficult film that most critics didn't like, but which is definitely worth seeking out.

The Old Boy press conference.

As for Old Boy, it provoked quite an interesting reaction from the critics and general audience. A small minority saw the film and were completely blown away by it. I'm guessing that perhaps many of these may have been people who follow Asian genre films, though certainly not all. The viewers who attended the press screening that I went to seemed to give it a mostly lukewarm response, though people seemed quite focused on the movie while it was playing. At the gala screening, apparently there was long and sustained applause from the audience -- which to be honest isn't that unusual for a gala screening, but compared to other films like the Hong Sang-soo it was a warm reception. Much of the commentary in the press focused on the film's violence, though a largely unmentioned undercurrent to many of the reviews was the film's origins in genre cinema instead of "serious" arthouse themes. It received mostly what I would term "grudgingly positive" reviews.

I covered the press conference for Screen and there were quite a few interesting comments from the director, cinematographer, and cast. A few highlights:

* Park originally planned to shoot the corridor fight sequence in over 100 shots, but in the end he decided to do it in just a single take. He said that it helped to emphasize the solitude of the main character in his battle of one man vs. twenty.

* As for violence, Park called it a "terrible thing" but said that there was sometimes a visual beauty in it. He says in his films, he thinks about the reasons for violence to occur, and most importantly, the results of that violence.

* Regarding the (supposedly) planned Hollywood remake, he said that he would prefer that someone take the actual film to U.S. viewers, but that it would be up to the new filmmakers to make it in their own way, and that he would not be connected with the project. He joked that his one hope was that a highly skilled director who could recreate the film in a more accomplished and moving way would NOT be found, because it would make him feel embarrassed. (Not much danger of that, I'd guess...)

* Park's instructions to his composer were to produce an impression of dizziness or vertigo, of the music spinning around the main character. After using a series of musical forms throughout like tango, etc. he ends the film with a funeral march.

* On the age difference between the two male leads, who in the film are supposed to be a similar age: Park said he on purpose cast the Oh Dae-soo character to look "a whole lot older" than the Lee Woo-jin character (a comment which drew a playful glare from Choi Min-shik). He said he pictured Woo-jin as stopping his growth after the event we see dramatized in a flashback at the end of the film (I'm trying not to give away spoilers here). He also wanted the effect of a younger man toying with an older one. Apparently he considered giving the Woo-jin character acne, but then decided it wasn't necessary.

* On vengeance stories: these are not new, Park said -- they run from Greek myths up until the present. He said his personal interest in vengeance stories is that private vengeance is outlawed in modern society, and that he is naturally drawn to make films about "forbidden territory".

Hong Sang-soo's Woman is the Future of Man did not go down well, I'm sad to say, except with those who had seen his previous works or were at least a little acquainted with the director's style. I wasn't able to attend the screening or press conference myself, but I heard that the gala screening had just the tiniest hint of applause, making for a somewhat awkward situation. Terrible reviews were also published in The Hollywood Reporter and (I'm ashamed to say it) Screen International. Not only terrible in the sense that they panned the film, but also terrible in the sense that obviously neither of these reviewers knew a thing about Hong, his reputation, or his previous works, and they simply trashed the film because it was incomprehensible for them. The Hollywood Reporter called it "amateurish", while the reviewer for Screen flailed around trying to figure out what Hong was trying to do, ultimately criticizing it for not being social commentary on Korean youth, for not being a modern-day Korean Jules and Jim, and for not being Tsai Ming-liang. A Korean critic I met at the festival was absolutely furious after reading the review, and I can't say I blame him at all. It's no different than someone reviewing a David Lynch film, and complaining that the story didn't make any sense (without bothering to watch any of his previous works).

Hong Sang-soo at Cannes.

On the day before his film was screened, I got a chance to do a one-on-one interview with Hong, which was quite an exciting opportunity. Although he said at one point that "it's far more important to watch my films and draw your own meaning from them, rather than listening my words," I did get a better feeling for his works after talking to him. A quick overview:

* On differences between Woman and his previous works: "For me, filmmaking is an expression of my being at the moment of making a film. Because I have changed in the time since I made my last film, there must be differences, but I don't start with a conscious plan that I will make this work different from my previous ones. I may have some intentions regarding the work, but they are not related to my previous films."

* On editing: "I think this is true of many filmmakers, but when I approach editing I consider the film as raw material shot by another director. Of course this is not as easy as it sounds, but I try. During the editing process I like to discover things. I may start with some intentions, but through making the film I discover something. If it is a substantial discovery, then my intentions may change..."

* On directors he admires: "Ozu, Eric Rohmer, some of Jean Renoir's works, some of John Ford, some Bresson (not all). There are many, many directors that I like... When I see artworks that I admire, it helps to give me a guideline, a foundation for my aesthetic judgement. In this way, I learn from them. When I find films, novels, or paintings that I like very much, it is like, "this is it." It is as if something inside me were trying to find a form or expression, and these artworks show me that it can be done."

* Hong's advice to younger filmmakers: "I try to start with a good question. A good question always comes from negating what is well-formed. How to view life, and such things. Then I try to view things or people or situations without any doctrine or ideology to interpret them. If I just accept existing interpretations, then I don't feel good -- it is like repetition, or producing something dead. I'm not sure if this would be helpful for young filmmakers...

I start with a very ordinary, banal situation, and this situation usually has something in it that makes me feel strongly. It's a stereotypical feeling, but very strong. I have this desire to look at it... Perhaps it's a blind feeling. I put it on the table, and I look at it. I open up, and these pieces surface. They are not related, they conflict with each other. But I try to find a pattern that makes all these pieces fit into one. That's what I do."

* On filmmaking and the self: "It's very helpful for me as a human being to make films. It stimulates me and encourages me. You search for some kind of form, and then you finalize something...

I'm still negating, I haven't got to the point where I'm over this negation, where I've found these small beliefs that are absolutely affirmative -- something I really believe in and am ready to talk about. As a person, I'm still in the process of negating...

Filmmaking is a reflection of the self, but filmmaking always ends and takes a certain form. When I finish a film, I feel like I have overcome a certain hurdle. It's really good for me as a human being, and I hope that for some people, my films will do the same thing."

An Old Boy poster on the Croisette.

My general first impressions of Cannes? I'd have to say it was mixed. I enjoyed the work I did, and I learned a lot, but I think if I just wanted to spend a week at a festival watching films, Cannes might be the last place I would go. I generally prefer smaller, more intimate festivals, but even among the big ones I get the impression that Berlin or Rotterdam places a much stronger focus on the films and the audience, compared to the promotional events, parties, sports cars, Hollywood stars, and everything else that grabs the spotlight away from cinema at Cannes. Film as art seems to rank third at the festival, behind industry and glamour. This is ironic because visiting critics still like to portray the event as kind of a cinephile's paradise. Compared to other festivals, it is not.

Cannes' strengths are more on the business side, both for popular films in the market and for the titles in the main competition. The huge concentration of press at the event means that buzz films get more worldwide exposure than they would at any other festival. For small arthouse films, a good reception at Cannes can turn your movie from a money-loser into a money-maker, and help it to reach many more viewers. It's a shame that Cannes so seldom uses this power it has to promote lesser-known films and directors, but for those lucky enough to get accepted into Cannes' exclusive club, the rewards can be large.

I had arrived back home in Seoul by the time Old Boy was presented with the Grand Prix, but needless to say I was quite happy for the film. Even some of the negative reviews that Old Boy received will help with promotion, and the award will certainly bring Park's film (and perhaps Korean cinema in general) to a wider audience. For that, I can't help but be grateful.

I'll end this festival report with more photos from the event:

The Carlton Hotel.

The Croisette.

A cocktail party above the Croisette.

The beach, adjacent to the main screening venues.

Yachts and cruise ships in the sea, come to visit the festival.

The "old city", a small historical corner of Cannes with restaurants and shops.

Park Chan-wook and Choi Min-shik doing interviews.

The Cannes market.

Cinema Service's booth in the market.

The KOFIC Pavilion.

Darcy on the beach.

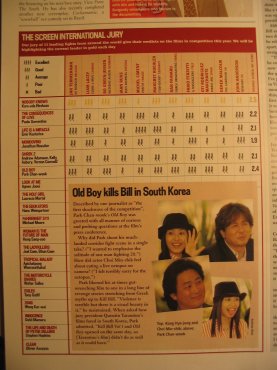

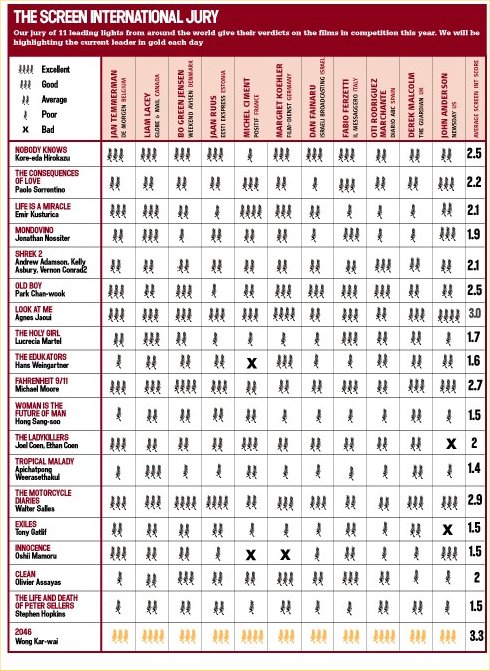

The Screen International critics' poll

Paolo Bertolin

Unlike for Darcy, it was not my first time in Cannes. I was there last year as well, when I was reporting for an Italian cinema magazine. This year things have changed, and apart from the usual contributions to some Italian publications, I was at the festival to write some articles for The Korea Times. I actually had presented my application for accreditation prior to getting in contact with the newspaper, but as soon as I knew that I could be their correspondent in Cannes, I decided to choose The Korea Times as my preferred media (when you ask the Cannes Press Office for an accreditation representing more than one media outlet you should always choose a preferred one) in order to have "Korea Times" written on my badge. I felt exceedingly cool walking around in Cannes with my pink badge, stating I was a Korean reporter, especially during this edition when Korean cinema was playing the part of the real talk of the town.

Apart from my own feelings of coolness, this year's festival marked a decidedly exciting development for those concerned with Korean cinema's destinies. As Darcy has already pointed out, it was the first time two Korean films were admitted in the main competition of the world's biggest and most prestigious film festival, and that is something that has to be considered for its impressive historical relevance. It was in fact no more recent than the year 2000 that a Korean film was first chosen to compete in Cannes (Im Kwon Taek's Chunhyang), and the total amount of Korean Cannes' competitors rose up to just two two years later, when Im's subsequent Chihwaseon was invited and eventually grabbed Best Director nods. So, in its only third admittance to Cannes' competitive arena, South Korean cinema was graced with the honour of two selections.

Apart from my own feelings of coolness, this year's festival marked a decidedly exciting development for those concerned with Korean cinema's destinies. As Darcy has already pointed out, it was the first time two Korean films were admitted in the main competition of the world's biggest and most prestigious film festival, and that is something that has to be considered for its impressive historical relevance. It was in fact no more recent than the year 2000 that a Korean film was first chosen to compete in Cannes (Im Kwon Taek's Chunhyang), and the total amount of Korean Cannes' competitors rose up to just two two years later, when Im's subsequent Chihwaseon was invited and eventually grabbed Best Director nods. So, in its only third admittance to Cannes' competitive arena, South Korean cinema was graced with the honour of two selections.

On one hand, in general terms, this has to be considered as a great reward, as each year no more than approx. 20 to 24 films from all over the world are chosen to run for the Palme d'Or, and at least three or four slots are reserved for national (French) productions. As Cannes is the place where world cinema's trends and main evolutions receive their definitive sanction and recognition (mainly thanks to the huge and pervasive media exposure), in unprecedentedly choosing two Korean films for competition, the festival selectors have given the world a strong signal of acknowledgment of a phenomenon that can not and has not to be ignored anymore: the absolute relevance, both in terms of artistic flourishing and of industry strength, of contemporary South Korean cinema. To give you a measure of how craved a competition slot in Cannes is and of how outstanding a two film selection in Cannes might be, I can mention a couple of anecdotes. Until the year 2000, only three countries had films competing in Cannes each and every year since the founding of the festival, namely France, bien sur!, the US and Italy. Coincidentally, the very first time Korea was in competition was also the very first time for Italy to be outside of it (unfortunate incidences of hurting mutual exclusions seem to punctuate the relations between the two countries...) and the Italian press (always encumberingly present at Cannes) made such a fuss that the following year Italy was consoled with two competition slots and a Palme d'Or to Nanni Moretti's The Son's Room. By the way, in a palpable (racist) retaliation against Asian films (eight competing titles in 2000), Chunhyang had such impressively bad press from Italian critics that the film was never released in my country. The list of countries that have had two (or more) films invited in competition in a single year over Cannes' 57 editions is thus obviously very restricted, including the likes of France, US, Italy, UK, Germany, Russia, Denmark, and from Asia just Japan and Taiwan (if we don't consider China and Hong Kong together).

On the other hand, concerning the specific choice of titles, selecting Park Chan-wook's Old Boy and Hong Sang-soo's Woman Is the Future of Man revealed decided braveness and edgy perspicuity from the festival's committee. Although Park's JSA competed in Berlin in 2001 and two of Hong's previous films were already selected for Cannes' sidebar section Un Certain Regard, both directors still lack wide recognition in the West, apart from the circles of Asiaphiles or Korean cinema buffs. Among Western journalists and critics in Cannes very few ever heard about Sympathy for Mr Vengeance or knew the titles of Hong's films, and even fewer could claim of having actually seen them. Of course there were exceptions, as for example French critics were familiar with Hong Sang-soo's work, as all of his films were released in Paris in the last year. But Park and Hong's admittance to Cannes' competition nevertheless marked the debut of two newcomers in the Major League of worldwide cinema, thus giving them on the one hand the recognition of being allowed among the world's top directors and on the other the (double-edged) opportunity of reaching the widest media exposure possible, along with all the connected alluring market prospects. Having Old Boy and Woman Is the Future of Man in competition at Cannes was good for Korean cinema as well, not only in terms of visibility, but also because the startling diversity of the two films could give international reporters a quite precise idea of the variety of its production and of the different tastes blended by its most prominent authors.

Anyway, it would not be honest to say that the response to Old Boy and Woman Is the Future of Man was enthusiastic or unanimous. It was mixed indeed, and far below my own personal expectations. Predictably, Old Boy generated sparklingly divergent views among the international press, although pros generally prevailed, with the notable exception of French critics who severely panned the film in the panel of Le Film Francais (the day after its screening Old Boy was standing in the very least position of this panel). To say it all, when seeing the film in Cannes at one of the press screenings, I could distinctly perceive a completely different atmosphere - I would say cold, at the least - from the (mesmerised) one that welcomed the film when I first saw it at Mifed.

Anyway, it would not be honest to say that the response to Old Boy and Woman Is the Future of Man was enthusiastic or unanimous. It was mixed indeed, and far below my own personal expectations. Predictably, Old Boy generated sparklingly divergent views among the international press, although pros generally prevailed, with the notable exception of French critics who severely panned the film in the panel of Le Film Francais (the day after its screening Old Boy was standing in the very least position of this panel). To say it all, when seeing the film in Cannes at one of the press screenings, I could distinctly perceive a completely different atmosphere - I would say cold, at the least - from the (mesmerised) one that welcomed the film when I first saw it at Mifed.

My forebodings could have never predicted instead the tepid, if not neatly negative response encountered by Hong's film. Some French friends who had seen the film at previews in Paris told me it was good, if not Palme d'Or material, but actually French critics (who mostly had seen Woman Is the Future of Man prior to its Cannes' presentation) were its very sole supporters. Hong undoubtedly collected some of the most unfairly unappreciative comments in Cannes this year, as Darcy sadly pointed out, but I myself have to admit that I am not an enthusiast of this film, which I consider by far his weakest one. True to say, Hong's fragile cinematic charm might have been affected by the crowded and loud context of Cannes, as the fact that French critics who liked the film had seen it in a more relaxed setting seems to suggest, but, as far as my own experience could be considered a valid test, I had seen Oh! Soo-jung/Virgin Stripped Bare by Her Bachelors in comparable circumstances (a late night screening at Rotterdam Film Festival) and that film bewitched me, magic that Woman Is the Future of Man was not capable of reproducing.

In any case, everybody in Cannes, and actually even before, agreed that Park and Hong's films would have been mutually excluding themselves in the jury's preferences, and, as Woman Is the Future of Man appeared as an unquestionable dark horse, Korean hopes for entering the palmares mostly relied on the ventilated (and subsequently confirmed) support of Tarantino towards Old Boy. In the end, as everybody knows, Old Boy won the Grand Prix, to the great discontent of French critics. No doubt this prize gives Park's film the great chance to prove its value with international audiences and perhaps develop a wide cult status, thus enlarging the interest among cinephiles about Korean cinema and its penetration in Western markets.

Meanwhile, it is more excruciating and sorrowing to consider Hong's hurting defeat. As an author who has been making some of the most stimulating and compelling films of Korean cinema's renaissance, his being unfairly mistreated and sometimes ridiculed at Cannes feels as an utmost injustice. Worse, not only Hong has missed his chance for the international recognition he deserved, he also unfortunately gained a label of fastidiously empty minimalism that risks to undermine his next outings on the international spotlight. To me, the saddest and most upsetting thing is that Hong was finally welcomed to Cannes' competition with this minor work that nevertheless was co-financed by powerful French producer Marin Karmitz and edited in Paris, while the far superior but not-France-backed Turning Gate was denied the invitation and Power of Kangwon Province and Oh! Soo-jung/Virgin Stripped Bare by Her Bachelors were confined to Un Certain Regard.

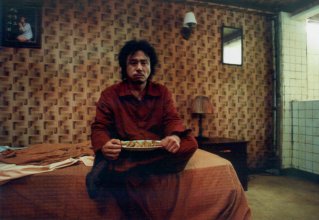

Korea aside, a few, quick and sparse notes on the other films I liked most in Cannes. My personal Palme d'Or could have been eclectically split between Old Boy and Thai Tropical Malady by Apichatpong Weerasethakul (pictured left), a challenging yet fascinating film that endured the hugest and noisiest insulting walkouts of the festival. Parted into two apparently unrelated halves telling respectively the story of an aborted gay romance between a soldier and a gentle country boy and the tale of a soldier who gets lost into the deep forest while hunting for a man-eating tiger, Tropical Malady is a spellbinding film about the animal side of human nature, about the double-sided innermost of our being and the attraction towards and need for unity of opposites. Another difficult yet utterly compelling film is Lucrecia Martel's La Nina Santa ("The Holy Girl"), a stylistically confident metaphor on moral corruption and misinterpreted faith in the Catholic bourgeoisie of Argentina. More palatable to general audiences, though slightly long, Nobody Knows by Kore-eda Hirokazu is a seducingly tender account of the life of some abandoned children in an uncaring Tokyo, told through superb documentary-style directing.

Korea aside, a few, quick and sparse notes on the other films I liked most in Cannes. My personal Palme d'Or could have been eclectically split between Old Boy and Thai Tropical Malady by Apichatpong Weerasethakul (pictured left), a challenging yet fascinating film that endured the hugest and noisiest insulting walkouts of the festival. Parted into two apparently unrelated halves telling respectively the story of an aborted gay romance between a soldier and a gentle country boy and the tale of a soldier who gets lost into the deep forest while hunting for a man-eating tiger, Tropical Malady is a spellbinding film about the animal side of human nature, about the double-sided innermost of our being and the attraction towards and need for unity of opposites. Another difficult yet utterly compelling film is Lucrecia Martel's La Nina Santa ("The Holy Girl"), a stylistically confident metaphor on moral corruption and misinterpreted faith in the Catholic bourgeoisie of Argentina. More palatable to general audiences, though slightly long, Nobody Knows by Kore-eda Hirokazu is a seducingly tender account of the life of some abandoned children in an uncaring Tokyo, told through superb documentary-style directing.

Apart from these competing titles, I would like to mention some films of the parallel sections: Pedro Almodovar's intoxicating festival-opener La Mala Educacion, Yousry Nasrallah's 4 1/2-hour passionate epic on the story of Palestine entitled La Porte du Soleil ("The Sun's Door"), Senegalese master Ousmane Sembene's plea against the brutal practice of female circumcision in Moolade, Jonathan Caouette's hurtingly autobiographical yet narcissistic experimental Tarnation, Israeli Keren Yedaya's deserved Camera d'Or winner Or, the rigorously filmed story of a girl who tries to save her mother from prostitution, and ends up becoming a prostitute as well, and a couple of Latin American gems, Los Muertos by Lisandro Alonso from Argentina and Uruguay's Whisky by Juan Pablo Rebella and Pablo Stoll, a film irresistibly filled with dry humour.