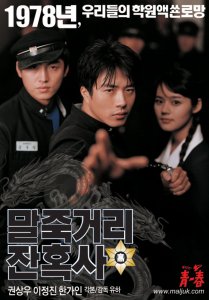

Once Upon a Time in High School: Spirit of Jeet Kune Do

("Maljukgeori Chanhoksa")

by Paolo Bertolin

(A word of excuse towards my reader. The following essay is by no means meant to provide a full-bodied and comprehensive analysis of "Once Upon a Time in High School: Spirit of Jeet Kune Do". It is instead to be regarded just as a "preparatory work for" or "work-in-progress towards" a more in-depth paper I am intending to work on at UCB, hopefully providing it with more substantial theoretical support and amending my indulgences in superficiality and biased partiality)

Once Upon a Time in High School: Spirit of Jeet Kune Do provides an excellent instance of what is best in Korean film today. On its surface a mere commercial entertainment product, the film reveals a hidden, multi-layered complexity that would seem more fitting to art-house fare. This perfect blend of entertainment and higher artistic ambitions is what really distinguishes the most accomplished Korean films of these days, and has made Korean cinema perhaps the most interesting national cinema of the last few years.

The case of Once Upon a Time in High School is especially interesting since it's mirrored in the "packaging" of the film itself. The promotional tagline for the film was in fact "1978-nyeon urideurui hakwon ekssyon romang", i.e. "1978, Our High School Action Romance", a definition that stresses the blending of two commercially appealing (literary and cinematic) genres of action and romance, in conformity with the fertile plying of the traditional Hollywood-based notion of genres that is current currency in contemporary Korean film, as well as a somewhat nostalgic(ally shared) setting in a recent past. Nostalgia too has been an intriguing, common trend among many Korean films of the last few years; a feature intrinsically related to the re-thinking of the country's intricate and tormented history, but also an appealing manner of connecting to the main demographics of Korean movies' viewership -- people in their 20s and 30s. On the other side, one has not to forget that director Yu Ha, who previously made Kyeorheuneun Mich'injisida (Marriage is a Crazy Thing), was a quite-renowned writer and poet before of venturing into filmmaking; thus, the luxurious SE of the DVD, besides two discs of film and special features, further rewards the buyer with a collection of Yu's poems.

The case of Once Upon a Time in High School is especially interesting since it's mirrored in the "packaging" of the film itself. The promotional tagline for the film was in fact "1978-nyeon urideurui hakwon ekssyon romang", i.e. "1978, Our High School Action Romance", a definition that stresses the blending of two commercially appealing (literary and cinematic) genres of action and romance, in conformity with the fertile plying of the traditional Hollywood-based notion of genres that is current currency in contemporary Korean film, as well as a somewhat nostalgic(ally shared) setting in a recent past. Nostalgia too has been an intriguing, common trend among many Korean films of the last few years; a feature intrinsically related to the re-thinking of the country's intricate and tormented history, but also an appealing manner of connecting to the main demographics of Korean movies' viewership -- people in their 20s and 30s. On the other side, one has not to forget that director Yu Ha, who previously made Kyeorheuneun Mich'injisida (Marriage is a Crazy Thing), was a quite-renowned writer and poet before of venturing into filmmaking; thus, the luxurious SE of the DVD, besides two discs of film and special features, further rewards the buyer with a collection of Yu's poems.

The original title itself encompasses the interplay between popular appeal and commitment to more ambitious designs. Translating into English as The Violent Story of Maljuk Street, it might at first seem a blatant revitalization of an exploitative, old-style kung fu movie vein, but a closer look unveils the narrative's true scope: a (topographically and, of course, historically) situated condemnation of the Korean school system that plays as an easy-to-read metaphor for a comprehensive censure of the military regime.

Behind the slick appearances of a romantic actioner set in a neighborhood high school in late 70s Seoul, the film delves deep into issues of remembering and re-thinking the recent past of Korea, in a way that encompasses neat criticism, as articulated through the trope of "coming of age" experienced by the main character Hyeon-su (played by Kwon Sang-woo). Nonetheless, the harsh criticism situated on the "macro" dimension is effortlessly encapsulated in parameters and paralleled by conflicts that are grounded in the "micro" dimension of everyday interaction: school life, teen heartaches and family ties. The relationship between Hyeon-su and his taekwondo master father exemplifies this dialectic between "macro" and "micro", since it stands in for an ampler representation and puts into question Korean family values and patriarchy.

In a fascinating way, the multi-dimensional discourse that Once Upon a Time in High School addresses convergences its multiple strains into one thematic and figurative neural center. Hyeon-su's body acts as this unique point of junction, anchored in an ongoing cinematic tradition of the Asian male body functioning as a simulacrum of conflicting and often resurgent virility. Yu Ha manages this complex task thanks to a culturally specific employment of transnational icon Bruce Lee (Lee or I So-ryong, in the Korean spelling). In the 70s, the American-born Lee represented a symbol of ethnic pride and subversion for humiliated Asian American male crowds and a widespread emblem of anti-colonial (both anti-Western and anti-Japanese) vindication among Chinese and more generally East Asian and South East Asian audiences. Yu instead re-accommodates the centrifugal subversion of Lee's icon to a national scale (which fits in with the rumor that, back in the 70s, many Koreans used to think of Lee as a co-national because of his surname). Yu stresses the non-traditional, border-crossing and hybrid nature of the Jeet Kune Do doctrine (the martial arts practice professed by Lee, an amalgam of features borrowed from kung fu, karate and muay thay), as opposed to Hyeon-su's rigid father's adherence to the national martial art of taekwondo. Accordingly, the film's opening sequence is circumscribed by a dual intertitle: the first reminds us that Lee's Jeet Kune Do was not taken into any serious account by martial arts masters; the following quotes Lee himself, highlighting Jeet Kune Do as meant not to indulge in the past, but in order to look forward. These tags ultimately reveal the key to the film itself, as magnified by the course of the narrative.

In a fascinating way, the multi-dimensional discourse that Once Upon a Time in High School addresses convergences its multiple strains into one thematic and figurative neural center. Hyeon-su's body acts as this unique point of junction, anchored in an ongoing cinematic tradition of the Asian male body functioning as a simulacrum of conflicting and often resurgent virility. Yu Ha manages this complex task thanks to a culturally specific employment of transnational icon Bruce Lee (Lee or I So-ryong, in the Korean spelling). In the 70s, the American-born Lee represented a symbol of ethnic pride and subversion for humiliated Asian American male crowds and a widespread emblem of anti-colonial (both anti-Western and anti-Japanese) vindication among Chinese and more generally East Asian and South East Asian audiences. Yu instead re-accommodates the centrifugal subversion of Lee's icon to a national scale (which fits in with the rumor that, back in the 70s, many Koreans used to think of Lee as a co-national because of his surname). Yu stresses the non-traditional, border-crossing and hybrid nature of the Jeet Kune Do doctrine (the martial arts practice professed by Lee, an amalgam of features borrowed from kung fu, karate and muay thay), as opposed to Hyeon-su's rigid father's adherence to the national martial art of taekwondo. Accordingly, the film's opening sequence is circumscribed by a dual intertitle: the first reminds us that Lee's Jeet Kune Do was not taken into any serious account by martial arts masters; the following quotes Lee himself, highlighting Jeet Kune Do as meant not to indulge in the past, but in order to look forward. These tags ultimately reveal the key to the film itself, as magnified by the course of the narrative.

The film's opening reel sets a brief prologue anteceding the main narration, picturing Hyeon-su still a kid and attending a film theatre to watch Bruce Lee's flicks (incidentally, this sequence offers a tasteful instance of sociological documentary as it portrays the now-lost, shabby neighborhood venues where martial arts films played to exclusively male audiences), then flashes forward to his high school days in the Maljuk neighborhood. The "establishing shots" of the high school where Hyeon-su is now enrolled immediately depict it as a military-governed institution, ruled by and operated through psychological and physical violence. Although inserted in an extremely tough and uncomfortable environment, Hyeon-su's character is represented as a model student and a shy, introverted guy. His ways are juxtaposed and contrasted to those of the bully Woo-sik, who becomes his best friend.

These two archetypical representations of manhood frontally collide when both boys start sharing an interest in the same girl, senior student Yu-jin. Hyeon-su is the kind of cute, sweet and sensitive guy who doesn't know how to dance, eats donuts and is left with a white moustache when drinking milk; naturally, he is totally helpless in dealing with the girl he has fallen for. Woo-sik, instead, is self-assured, confident and masculine, fearlessly engages in fights, regularly indulges in disco-dancing and resolutely chases girls he wants to seduce; of course, his interest in Yu-jin is felt as just a passing itch.

These two archetypical representations of manhood frontally collide when both boys start sharing an interest in the same girl, senior student Yu-jin. Hyeon-su is the kind of cute, sweet and sensitive guy who doesn't know how to dance, eats donuts and is left with a white moustache when drinking milk; naturally, he is totally helpless in dealing with the girl he has fallen for. Woo-sik, instead, is self-assured, confident and masculine, fearlessly engages in fights, regularly indulges in disco-dancing and resolutely chases girls he wants to seduce; of course, his interest in Yu-jin is felt as just a passing itch.

When faced with failure on the several fronts of his private life (school, love, paternal incomprehension), Hyeon-su almost reaches the verge of suicide. This occurs precisely right after his father has scolded him for his bad grades: a ferocious reminder that if he does not get into college, he will never be anything more than a "surplus man". This apparently hackneyed detail actually sutures the "micro" of Hyeon-su's unbearable state of frustration and depression with the "macro" dimension of an unforgiving merit-driven and coldly profit-oriented (pseudo-)military society.

The subsequent plot development therefore conveys an act of upheaval affecting both the micro and macro dimensions involved in the film's textual scheme. Hyeon-su realizes altogether what he can and has to do: he becomes conscious of his body, of his manhood, and starts working on it, building it up. He hence rebels factually against his previous self, against what he has been up to the present, and symbolically both against his father, who only preaches through physical abuse, and against the whole system of military dictatorship as embodied in the school institution. Through intensive training in Jeet Kune Do, Hyeon-su reshapes his body from "soft" to "hard", switching from model student to muscular tough. When Hyeon-su starts doing push ups, he's still wearing his school uniform; as his workout progresses, his body starts being exposed as it takes on a new shape. Eventually, Hyeon-su stands in front of a mirror, displaying his perfectly defined physique and posing as a hard-hitting hoodlum; he's no more the puppy-eyed, naive kid we met at the beginning of the film.

Quite meaningfully, this re-configuration of Hyeon-su's body and maleness occurs immediately after the disappearance from the narrative of model and rival Woo-sik, of his expunction from the visual space of representation. The reshaping of Hyeon-su's body, then, not only incorporates a tangible acknowledgement of a tormented coming of age, but it also can be assimilated to a partial transfer or investment of male identity features up to the moment embodied by Woo-sik, in an authentic process of fusion that inevitably subsumes an equal measure of loss and effacement (Hyeon-su's timidity and cuteness). This ultimate conceptual conjunction of the two main male bodies of the film - Woo-sik vanishes, but he's "re-acted", "re--lived" inhabiting Hyeon-su's new body -- educes a stream of homosexual undercurrents, perceivable in Hyeon-su's languid, somehow desiring gazes, whose diegetic angle of direction awkwardly points more towards Woo-sik than to Yu-jin. Gazes that thus project a need of completion and union conjugated in the tense of being rather than physical having.

The final act eventually stages the new Hyeon-su's rebellion against the "oppressor", personified by a senior student who acts as school patrol. His target inevitably represents the quintessential product of the conformed embracing of a system Hyeon-su has chosen to refuse, as well as its lower end vicious warden. The crucial face-off, as with previous instances of fights and brawls, abjures the superhuman and choreographic modes of Bruce Lee's films; violence all throughout Once Upon a Time in High School emerges as realistically dirty and exhausting, and as a result more disturbing and harrowing. After the fight, Hyeon-su shouts a line that seals emblematically the merging of micro with macro, of his own individual uprising with a full-bodied attack to the system: "Fuck all the schools in Korea!"

Quite meaningfully, this re-configuration of Hyeon-su's body and maleness occurs immediately after the disappearance from the narrative of model and rival Woo-sik, of his expunction from the visual space of representation. The reshaping of Hyeon-su's body, then, not only incorporates a tangible acknowledgement of a tormented coming of age, but it also can be assimilated to a partial transfer or investment of male identity features up to the moment embodied by Woo-sik, in an authentic process of fusion that inevitably subsumes an equal measure of loss and effacement (Hyeon-su's timidity and cuteness). This ultimate conceptual conjunction of the two main male bodies of the film - Woo-sik vanishes, but he's "re-acted", "re--lived" inhabiting Hyeon-su's new body -- educes a stream of homosexual undercurrents, perceivable in Hyeon-su's languid, somehow desiring gazes, whose diegetic angle of direction awkwardly points more towards Woo-sik than to Yu-jin. Gazes that thus project a need of completion and union conjugated in the tense of being rather than physical having.

The final act eventually stages the new Hyeon-su's rebellion against the "oppressor", personified by a senior student who acts as school patrol. His target inevitably represents the quintessential product of the conformed embracing of a system Hyeon-su has chosen to refuse, as well as its lower end vicious warden. The crucial face-off, as with previous instances of fights and brawls, abjures the superhuman and choreographic modes of Bruce Lee's films; violence all throughout Once Upon a Time in High School emerges as realistically dirty and exhausting, and as a result more disturbing and harrowing. After the fight, Hyeon-su shouts a line that seals emblematically the merging of micro with macro, of his own individual uprising with a full-bodied attack to the system: "Fuck all the schools in Korea!"

The subsequent penultimate chapter, which sees Hyeon-su's father presenting formal apologies to the mother of the beaten student facing his hospital bed, and then father and son silently walking back home, seems to take a step backward, as it encompasses a newly-(re)found(ed) acknowledgment of filial devotion. Still, on the one hand, this passage appears based upon a mutual recognition and change of attitude (Hyeon-su steps into adulthood as he's now entitled to make his own choice, no matter if it ends up being congruent with his father's wishes); but, on the other hand, as positioned in the conspicuous interplay enacted by the whole film, the denial a posteriori of Hyeon-su's act only takes place on the micro dimension, in a recognition of the desperate and strenuous gratuity of its violence, without losing its representational and symbolic relevance projected onto the macro level of issues of institutionalized violence and the totalitarian regime, as well as onto the comprehensive discourse of the film.

The subsequent penultimate chapter, which sees Hyeon-su's father presenting formal apologies to the mother of the beaten student facing his hospital bed, and then father and son silently walking back home, seems to take a step backward, as it encompasses a newly-(re)found(ed) acknowledgment of filial devotion. Still, on the one hand, this passage appears based upon a mutual recognition and change of attitude (Hyeon-su steps into adulthood as he's now entitled to make his own choice, no matter if it ends up being congruent with his father's wishes); but, on the other hand, as positioned in the conspicuous interplay enacted by the whole film, the denial a posteriori of Hyeon-su's act only takes place on the micro dimension, in a recognition of the desperate and strenuous gratuity of its violence, without losing its representational and symbolic relevance projected onto the macro level of issues of institutionalized violence and the totalitarian regime, as well as onto the comprehensive discourse of the film.

The epilogue of Once Upon a Time in High School humorously plays as a structural parallel to the overture and as a coda glossing on the legacy of Bruce Lee's icon. Opposing Lee to new martial arts superstar Jackie Chan, Yu stresses a changing of the times and once again a purposefully enhanced connection between cinema and cinematic icons and the characters' fate. On a deeper level, this represents a remarkable device of inscribing into the text itself a symmetrical mirroring to the proceeding the author is also consciously enacting: to convey a thought-provoking discourse on Korea's past and Korean identity by the means of (commercial) cinema.